Analytic number theory

Analytic number theory can be split up into two major parts, divided more by the type of problems they attempt to solve than fundamental differences in technique.

The prime number theorem then states that x / ln(x) is a good approximation to π(x), in the sense that the limit of the quotient of the two functions π(x) and x / ln(x) as x approaches infinity is 1: known as the asymptotic law of distribution of prime numbers.

Adrien-Marie Legendre conjectured in 1797 or 1798 that π(a) is approximated by the function a/(A ln(a) + B), where A and B are unspecified constants.

Carl Friedrich Gauss considered the same question: "Im Jahr 1792 oder 1793" ('in the year 1792 or 1793'), according to his own recollection nearly sixty years later in a letter to Encke (1849), he wrote in his logarithm table (he was then 15 or 16) the short note "Primzahlen unter

In 1838 Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet came up with his own approximating function, the logarithmic integral li(x) (under the slightly different form of a series, which he communicated to Gauss).

Johann Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet is credited with the creation of analytic number theory,[6] a field in which he found several deep results and in proving them introduced some fundamental tools, many of which were later named after him.

In 1837 he published Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions, using mathematical analysis concepts to tackle an algebraic problem and thus creating the branch of analytic number theory.

[8] In two papers from 1848 and 1850, the Russian mathematician Pafnuty L'vovich Chebyshev attempted to prove the asymptotic law of distribution of prime numbers.

His work is notable for the use of the zeta function ζ(s) (for real values of the argument "s", as are works of Leonhard Euler, as early as 1737) predating Riemann's celebrated memoir of 1859, and he succeeded in proving a slightly weaker form of the asymptotic law, namely, that if the limit of π(x)/(x/ln(x)) as x goes to infinity exists at all, then it is necessarily equal to one.

Hiervon wäre allerdings ein strenger Beweis zu wünschen; ich habe indess die Aufsuchung desselben nach einigen flüchtigen vergeblichen Versuchen vorläufig bei Seite gelassen, da er für den nächsten Zweck meiner Untersuchung entbehrlich schien.

Of course one would wish for a rigorous proof here; I have for the time being, after some fleeting vain attempts, provisionally put aside the search for this, as it appears dispensable for the next objective of my investigation."

Bernhard Riemann made some famous contributions to modern analytic number theory.

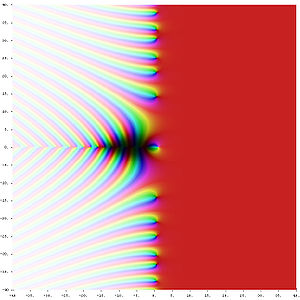

He made a series of conjectures about properties of the zeta function, one of which is the well-known Riemann hypothesis.

Extending the ideas of Riemann, two proofs of the prime number theorem were obtained independently by Jacques Hadamard and Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin and appeared in the same year (1896).

Specifically, the breakthroughs by Yitang Zhang, James Maynard, Terence Tao and Ben Green have all used the Goldston–Pintz–Yıldırım method, which they originally used to prove that[15][16][17][18][19][20]

Developments within analytic number theory are often refinements of earlier techniques, which reduce the error terms and widen their applicability.

The needs of Diophantine approximation are for auxiliary functions that are not generating functions—their coefficients are constructed by use of a pigeonhole principle—and involve several complex variables.

The fields of Diophantine approximation and transcendence theory have expanded, to the point that the techniques have been applied to the Mordell conjecture.

Instead, they give approximate bounds and estimates for various number theoretical functions, as the following examples illustrate.

Remarkably, the main term in Riemann's formula was exactly the above integral, lending substantial weight to Gauss's conjecture.

Riemann found that the error terms in this expression, and hence the manner in which the primes are distributed, are closely related to the complex zeros of the zeta function.

Using Riemann's ideas and by getting more information on the zeros of the zeta function, Jacques Hadamard and Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin managed to complete the proof of Gauss's conjecture.

More generally, the same question can be asked about the number of primes in any arithmetic progression a + nq for any integer n. In one of the first applications of analytic techniques to number theory, Dirichlet proved that any arithmetic progression with a and q coprime contains infinitely many primes.

One of the most important problems in additive number theory is Waring's problem, which asks whether it is possible, for any k ≥ 2, to write any positive integer as the sum of a bounded number of kth powers, The case for squares, k = 2, was answered by Lagrange in 1770, who proved that every positive integer is the sum of at most four squares.

The general case was proved by Hilbert in 1909, using algebraic techniques which gave no explicit bounds.

Again, the difficult part and a great achievement of analytic number theory is obtaining specific upper bounds on the error term E(r).

Euler was also the first to use analytical arguments for the purpose of studying properties of integers, specifically by constructing generating power series.

In his 1859 paper, Riemann conjectured that all the "non-trivial" zeros of ζ lie on the line

For example, under the assumption of the Riemann Hypothesis, the error term in the prime number theorem is

Some examples are (i) Montgomery's pair correlation conjecture and the work that initiated from it, (ii) the new results of Goldston, Pintz and Yilidrim on small gaps between primes, and (iii) the Green–Tao theorem showing that arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions of primes exist.