Analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry studies and uses instruments and methods to separate, identify, and quantify matter.

[1] In practice, separation, identification or quantification may constitute the entire analysis or be combined with another method.

Instrumental methods may be used to separate samples using chromatography, electrophoresis or field flow fractionation.

Analytical chemistry is also focused on improvements in experimental design, chemometrics, and the creation of new measurement tools.

The first instrumental analysis was flame emissive spectrometry developed by Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff who discovered rubidium (Rb) and caesium (Cs) in 1860.

[5] The separation sciences follow a similar time line of development and also became increasingly transformed into high performance instruments.

Many methods, once developed, are kept purposely static so that data can be compared over long periods of time.

These techniques also tend to form the backbone of most undergraduate analytical chemistry educational labs.

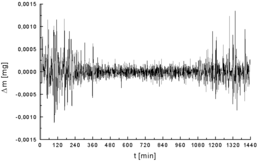

The gravimetric analysis involves determining the amount of material present by weighing the sample before and/or after some transformation.

Titration involves the gradual addition of a measurable reactant to an exact volume of a solution being analyzed until some equivalence point is reached.

Most familiar to those who have taken chemistry during secondary education is the acid-base titration involving a color-changing indicator, such as phenolphthalein.

Mass spectrometry measures mass-to-charge ratio of molecules using electric and magnetic fields.

In a mass spectrometer, a small amount of sample is ionized and converted to gaseous ions, where they are separated and analyzed according to their mass-to-charge ratios.

Electroanalytical methods measure the potential (volts) and/or current (amps) in an electrochemical cell containing the analyte.

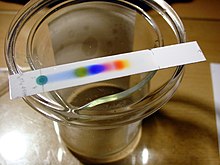

[13] In Thin-layer chromatography, the analyte mixture moves up and separates along the coated sheet under the volatile mobile phase.

Devices that integrate (multiple) laboratory functions on a single chip of only millimeters to a few square centimeters in size and that are capable of handling extremely small fluid volumes down to less than picoliters.

This allows for the determination of the amount of a chemical in a material by comparing the results of an unknown sample to those of a series of known standards.

If the concentration of element or compound in a sample is too high for the detection range of the technique, it can simply be diluted in a pure solvent.

Sometimes an internal standard is added at a known concentration directly to an analytical sample to aid in quantitation.

Standard addition can be applied to most analytical techniques and is used instead of a calibration curve to solve the matrix effect problem.

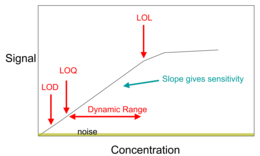

One of the most important components of analytical chemistry is maximizing the desired signal while minimizing the associated noise.

The root mean square value of the thermal noise in a resistor is given by[22] where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, R is the resistance, and

Sources of electromagnetic noise are power lines, radio and television stations, wireless devices, compact fluorescent lamps[23] and electric motors.

Examples of hardware noise reduction are the use of shielded cable, analog filtering, and signal modulation.

Analytical chemistry research is largely driven by performance (sensitivity, detection limit, selectivity, robustness, dynamic range, linear range, accuracy, precision, and speed), and cost (purchase, operation, training, time, and space).

Advances in design of diode lasers and optical parametric oscillators promote developments in fluorescence and ionization spectrometry and also in absorption techniques where uses of optical cavities for increased effective absorption pathlength are expected to expand.

[citation needed] Great effort is being put into shrinking the analysis techniques to chip size.

Although there are few examples of such systems competitive with traditional analysis techniques, potential advantages include size/portability, speed, and cost.

[citation needed] Analytical chemistry has played a critical role in the understanding of basic science to a variety of practical applications, such as biomedical applications, environmental monitoring, quality control of industrial manufacturing, forensic science, and so on.

[25] The recent developments in computer automation and information technologies have extended analytical chemistry into a number of new biological fields.