Vulgate

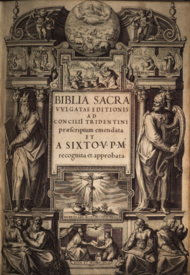

[4] The Catholic Church affirmed the Vulgate as its official Latin Bible at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), though there was no authoritative edition of the book at that time.

The Clementine edition of the Vulgate became the standard Bible text of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, and remained so until 1979 when the Nova Vulgata was promulgated.

An example of the use of this word in this sense at the time is the title of the 1538 edition of the Latin Bible by Erasmus: Biblia utriusque testamenti juxta vulgatam translationem.

[22] By the time of Damasus' death in 384, Jerome had completed this task, together with a more cursory revision from the Greek Common Septuagint of the Vetus Latina text of the Psalms in the Roman Psalter, a version which he later disowned and is now lost.

Jerome's extensive use of exegetical material written in Greek, as well as his use of the Aquiline and Theodotiontic columns of the Hexapla, along with the somewhat paraphrastic style[29] in which he translated, makes it difficult to determine exactly how direct the conversion of Hebrew to Latin was.

43 of his The City of God that "in our own day the priest Jerome, a great scholar and master of all three tongues, has made a translation into Latin, not from Greek but directly from the original Hebrew.

[34] According to Amanda Benckhuysen: "Jerome omits from the Vulgate the phrase “who was with her” in Genesis 3:6, making Eve doubly culpable for the fall and responsible for Adam’s sin.

[40] In addition, many medieval Vulgate manuscripts included Jerome's epistle number 53, to Paulinus bishop of Nola, as a general prologue to the whole Bible.

The individual books varied in quality of translation and style, and different manuscripts and quotations witness wide variations in readings.

[59] In places Jerome adopted readings that did not correspond to a straightforward rendering either of the Vetus Latina or the Greek text, so reflecting a particular doctrinal interpretation; as in his rewording panem nostrum supersubstantialem at Matthew 6:11.

Until the 20th century, it was commonly assumed that the surviving Roman Psalter represented Jerome's first attempted revision, but more recent scholarship—following de Bruyne—rejects this identification.

[62] Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Baruch (with the Letter of Jeremiah) are included in the Vulgate, and are purely Vetus Latina translations which Jerome did not touch.

Bogaert argues that this practice arose from an intention to conform the Vulgate text to the authoritative canon lists of the 5th/6th century, where 'two books of Ezra' were commonly cited.

[66] The Council of Trent cited long usage in support of the Vulgate's magisterial authority: Moreover, this sacred and holy Synod,—considering that no small utility may accrue to the Church of God, if it be made known which out of all the Latin editions, now in circulation, of the sacred books, is to be held as authentic,—ordains and declares, that the said old and vulgate edition, which, by the lengthened usage of so many years, has been approved of in the Church, be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.

[69] Later, in the 20th century, Pope Pius XII declared the Vulgate as "free from error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals" in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu: Hence this special authority or as they say, authenticity of the Vulgate was not affirmed by the Council particularly for critical reasons, but rather because of its legitimate use in the Churches throughout so many centuries; by which use indeed the same is shown, in the sense in which the Church has understood and understands it, to be free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals; so that, as the Church herself testifies and affirms, it may be quoted safely and without fear of error in disputations, in lectures and in preaching [...]"[70]The inerrancy is with respect to faith and morals, as it says in the above quote: "free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals", and the inerrancy is not in a philological sense: [...] and so its authenticity is not specified primarily as critical, but rather as juridical.

[71] In about 1455, the first Vulgate published by the moveable type process was produced in Mainz by a partnership between Johannes Gutenberg and banker John Fust (or Faust).

[73] Aside from its use in prayer, liturgy, and private study, the Vulgate served as inspiration for ecclesiastical art and architecture, hymns, countless paintings, and popular mystery plays.

[76] Before the publication of Pius XII's Divino afflante Spiritu, the Vulgate was the source text used for many translations of the Bible into vernacular languages.

The Codex Fuldensis, dating from around 545, contains most of the New Testament in the Vulgate version, but the four gospels are harmonised into a continuous narrative derived from the Diatessaron.

[82] "Although, in contrast to Alcuin, Theodulf [of Orleans] clearly developed an editorial programme, his work on the Bible was far less influential than that of hs slightly older contemporary.

[86] Though the advent of printing greatly reduced the potential of human error and increased the consistency and uniformity of the text, the earliest editions of the Vulgate merely reproduced the manuscripts that were readily available to publishers.

Other corrected editions were published by Xanthus Pagninus in 1518, Cardinal Cajetan, Augustinus Steuchius in 1529, Abbot Isidorus Clarius (Venice, 1542) and others.

This was the first complete Bible with full chapter and verse divisions and became the standard biblical reference text for late-16th century Reformed theology.

After the Reformation, when the Catholic Church strove to counter Protestantism and refute its doctrines, the Vulgate was declared at the Council of Trent to "be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.

However, Bruce Metzger, an American biblical scholar, believes that the printing inaccuracies may have been a pretext and that the attack against this edition had been instigated by the Jesuits, "whom Sixtus had offended by putting one of Bellarmine's books on the 'Index' ".

[102][103] This was eventually published as Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Iesu Christi Latine, secundum editionem sancti Hieronymi in three volumes between 1889 and 1954.

[107] In 1907, Pope Pius X commissioned the Benedictine monks to prepare a critical edition of Jerome's Vulgate, entitled Biblia Sacra iuxta latinam vulgatam versionem.

[108] This text was originally planned as the basis for a revised complete official Bible for the Catholic Church to replace the Clementine edition.

By the 1970s, as a result of liturgical changes that had spurred the Vatican to produce a new translation of the Latin Bible, the Nova Vulgata, the Benedictine edition was no longer required for official purposes,[114] and the abbey was suppressed in 1984.

It contains two Psalters, the Gallicanum and the juxta Hebraicum, which are printed on facing pages to allow easy comparison and contrast between the two versions.