Arc length

Development of a formulation of arc length suitable for applications to mathematics and the sciences is a focus of calculus.

In the most basic formulation of arc length for a parametric curve (thought of as the trajectory of a particle), the arc length is obtained by integrating the speed of the particle over the path.

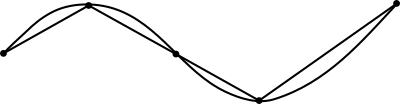

The lengths of the successive approximations will not decrease and may keep increasing indefinitely, but for smooth curves they will tend to a finite limit as the lengths of the segments get arbitrarily small.

that is an upper bound on the length of all polygonal approximations (rectification).

These curves are called rectifiable and the arc length is defined as the number

A signed arc length can be defined to convey a sense of orientation or "direction" with respect to a reference point taken as origin in the curve (see also: curve orientation and signed distance).

is continuously differentiable, then it is simply a special case of a parametric equation where

Curves with closed-form solutions for arc length include the catenary, circle, cycloid, logarithmic spiral, parabola, semicubical parabola and straight line.

In most cases, including even simple curves, there are no closed-form solutions for arc length and numerical integration is necessary.

The 15-point Gauss–Kronrod rule estimate for this integral of 1.570796326808177 differs from the true length of

by 1.3×10−11 and the 16-point Gaussian quadrature rule estimate of 1.570796326794727 differs from the true length by only 1.7×10−13.

Evaluating the derivative requires the chain rule for vector fields:

is the first fundamental form coefficient), so the integrand of the arc length integral can be written as

So for a curve expressed in polar coordinates, the arc length is:

So for a curve expressed in spherical coordinates, the arc length is

A very similar calculation shows that the arc length of a curve expressed in cylindrical coordinates is

Two units of length, the nautical mile and the metre (or kilometre), were originally defined so the lengths of arcs of great circles on the Earth's surface would be simply numerically related to the angles they subtend at its centre.

applies in the following circumstances: The lengths of the distance units were chosen to make the circumference of the Earth equal 40000 kilometres, or 21600 nautical miles.

Those are the numbers of the corresponding angle units in one complete turn.

[5] This modern ratio differs from the one calculated from the original definitions by less than one part in 10,000.

For much of the history of mathematics, even the greatest thinkers considered it impossible to compute the length of an irregular arc.

Although Archimedes had pioneered a way of finding the area beneath a curve with his "method of exhaustion", few believed it was even possible for curves to have definite lengths, as do straight lines.

In particular, by inscribing a polygon of many sides in a circle, they were able to find approximate values of π.

[6][7] In the 17th century, the method of exhaustion led to the rectification by geometrical methods of several transcendental curves: the logarithmic spiral by Evangelista Torricelli in 1645 (some sources say John Wallis in the 1650s), the cycloid by Christopher Wren in 1658, and the catenary by Gottfried Leibniz in 1691.

In 1659, Wallis credited William Neile's discovery of the first rectification of a nontrivial algebraic curve, the semicubical parabola.

Before the full formal development of calculus, the basis for the modern integral form for arc length was independently discovered by Hendrik van Heuraet and Pierre de Fermat.

In 1659 van Heuraet published a construction showing that the problem of determining arc length could be transformed into the problem of determining the area under a curve (i.e., an integral).

[9] In 1660, Fermat published a more general theory containing the same result in his De linearum curvarum cum lineis rectis comparatione dissertatio geometrica (Geometric dissertation on curved lines in comparison with straight lines).

[10] Building on his previous work with tangents, Fermat used the curve whose tangent at x = a had a slope of so the tangent line would have the equation Next, he increased a by a small amount to a + ε, making segment AC a relatively good approximation for the length of the curve from A to D. To find the length of the segment AC, he used the Pythagorean theorem: which, when solved, yields In order to approximate the length, Fermat would sum up a sequence of short segments.

Another example of a curve with infinite length is the graph of the function defined by f(x) = x sin(1/x) for any open set with 0 as one of its delimiters and f(0) = 0.