United States Army Air Service

The National Defense Act of 1920 assigned the Air Service the status of "combatant arm of the line" of the United States Army with a major general in command.

The reorganization of the Aviation Section had been inadequate in resolving problems in training, leaving the United States totally unprepared to fight an air war in Europe.

The Board dispatched Major Raynal C. Bolling, a lawyer and military aviation pioneer, together with a commission of over 100 members, to Europe in the summer of 1917 to determine American aircraft needs, recommend priorities for acquisition and production, and negotiate prices and royalties.

[10] Moreover, the largely wood and fabric airframe designs of World War I did not lend themselves to being made with the mass production methods of the automotive industry, which used considerable amounts of metallic materials instead, and the priority of mass-producing spare parts was neglected.

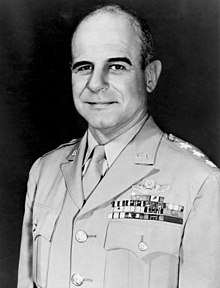

Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher was appointed to the vacancy on January 2, 1919, but the patchwork nature of laws and executive orders that had created the various parts of the Air Service prevented him from exercising all their legal powers and ending the unity of command problems caused by dual authority.

[26] Pilots in Europe completed an advanced phase in which they received specialized training in pursuit, bombing, or observation at Air Service schools acquired from the French at Issoudun, Clermont-Ferrand, and Tours, respectively.

On May 3, 1918, Col. Henry H. Arnold, Assistant Director of the DMA, was ordered to put together a daily route for moving mail by airplane between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

[33] Sent to Europe in March 1917 as an observer, Lieutenant Colonel Billy Mitchell arrived in Paris just four days after the United States declared war[34] and established an office for the American "air service."

This resulted in considerable resentment from Mitchell's smaller staff already in place, many of whom in key positions, including Bolling, Dodd and Lt. Col. Edgar S. Gorrell, were immediately displaced.

On August 30, 1917, the American and French governments agreed to a contract for the purchase of 1,500 Breguet 14 B.2 bombers-reconnaissance planes; 2,000 SPAD XIII and 1,500 Nieuport 28 pursuits for delivery by July 1, 1918.

The first U.S. aviator killed in action during aerial combat occurred March 8, 1918, when Captain James E. Miller, commanding the 95th Pursuit Squadron, was shot down while on a voluntary patrol near Reims.

Eddie Rickenbacker, and the 27th Pursuit Squadron, which had "balloon buster" 1st Lt. Frank Luke as one of its pilots, achieved distinguished records in combat and remained a permanent part of the air forces.

Promptly after the armistice, the AEF formed the Third United States Army to march immediately into Germany, occupy the Coblenz area, and be prepared to resume combat if peace treaty negotiations failed.

Although the leaders of the reorganized Air Service persuaded the General Staff to increase the combat strength to 20 squadrons by 1923, the balloon force was demobilized, including dirigibles, and personnel shrank even further, to just 880 officers.

However this also legislated the form of the Air Service to that desired by the General Staff to maintain the aviation arm as an auxiliary component controlled by ground commanders in furtherance of the mission of the infantry.

The primary missions of the Air Service were observation and pursuit aviation, and its tactical squadrons in the United States were controlled by the commanders of nine corps areas and three overseas departments created by the Act, primarily in support of the ground forces.

The Air Service Tactical School was set up at Langley Field, Virginia, to train officers for higher command and to instruct in doctrine and the employment of military aviation.

The doctrinal differences between the military services were both defined and intensified by struggles for funds caused by the skimpy budgets authorized for the War Department, first by the penurious policies of the Republican administrations in the 1920s, and then by the fiscal realities of the Great Depression.

Instead he became Third Assistant Executive (in effect, S-3), chief of the new Training and Operations Group, where he installed like-minded airmen who had served with him France as division heads and used the position to expound his theories.

[87][n 43] Although two bills to create Mitchell's proposed department were introduced, in the Senate by Sen. Harry S. New of Indiana and in the House by Rep. Charles F. Curry of California, and initially garnered strong support, the opposition of the Army's wartime leaders (especially General Pershing) frustrated the effort at the start.

[n 44] In August 1919 Gen. Menoher was assigned to chair a board consisting of himself and three other generals, all artillery officers and former infantry division commanders, appointed to report back to Congress on the proposed legislation.

He underwent flight training and obtained his wings, then issued a series of reports to the War Department emphasizing the need to expand and modernize the Air Service.

The Secretary of War convened the Lassiter Board in 1923, composed of general staff officers who fully endorsed Patrick's views, and adopted the policy in regulations.

[94][n 48] Patrick's proposal that appropriations for the Air Service be coordinated with the larger budget of Naval aviation (in effect, shared), was rejected by the Navy, and the reorganization could not be implemented.

Mitchell testified before the committee and, upset by the failure of the War Department to even negotiate with the Navy in order to save the reforms of the Lassiter Board, harshly criticized Army leadership and attacked other witnesses.

He was reduced in rank to colonel by Secretary Weeks and exiled to the Eighth Corps Area in San Antonio as air officer, where his continuing, reckless, and increasingly strident criticisms prompted President Calvin Coolidge to order his court-martial.

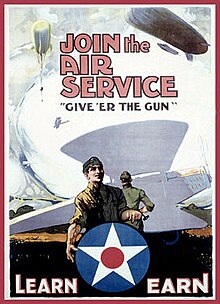

On August 14, 1919, the All American Pathfinders, a provisional squadron, began a cross-country educational tour that supported the "1919 Air Service Transcontinental Recruiting Convoy"[98] from Hazelhurst Field to California.

Mitchell himself set a world speed record of 222.97 mph (358.84 km/h) over a closed course in a Curtiss R-6 racer on October 18, 1922, at the Pulitzer Trophy competition of the 1922 National Air Races.

One month later, taking off at 1:00 a.m. of March 25, he repeated the attempt going in the opposite direction, but developed engine problems while flying low in a fog near Crowville, Louisiana, southeast of Monroe.

[100] On September 4, 1922, Doolittle completed the first transcontinental crossing in a single day, from Pablo Beach to Rockwell Field, in 21 hours, 20 minutes, a distance of 2,163 mi (3,481 km) flying a DH-4 of the 90th Squadron.