Army of Flanders

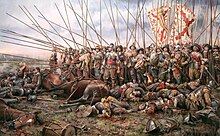

[4] Sustained at huge cost and at significant distances from Spain via the Spanish Road, the Army of Flanders also became infamous for successive mutinies and its ill-disciplined activity on and off the battlefield, including the sack of Antwerp in 1576.

[8] It was envisaged at this stage that the total number might potentially reach 70,000, composed of 60,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, under the command of Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba.

In the end, only 10,000 Spanish and a regiment of German infantry under Count Alberic de Lodron were sent, although their formation, dispatch and march north was a considerable accomplishment for the time.

[19] The cost of recruiting for the Army created tensions between Philip II's policy in the Netherlands, and his need to maintain a strong presence in the Mediterranean against the Ottoman Empire.

Drawn from the lower classes, they made up a large percentage of the overall size of the Army in the field,[26] and represented a considerable logistical burden in campaigns.

Alba set up a military hospital at Mechelen in the Duchy of Brabant in 1567; it was closed the following year, but after many complaints by mutineers it reopened in 1585, ultimately having 49 staff and 330 beds, paid for partially by the troops.

[27] After 1609, a number of small barracks (baraques, called after the French version of the Catalan barraca) were created away from the main urban centres to house the Army – a move that was eventually copied by other nations.

The large areas of flat ground, the platteland, was criss-crossed by rivers and drainage channels, dotted by numerous towns and cities well placed to dominate the surrounding landscape, increasingly defended with polygonal fortifications.

The Spanish experiences fighting the Swedish, with their more flexible, firepower-oriented tactics of open battle, resulted in a decision to alter the balance of the Flanders tercios in 1634.

[42] By contrast, even by early modern standards the Army was considered very ill-disciplined off the field, as illustrated by a colloquial Spanish phrase in response to unruly behaviour which came rhetorically to question whether the person believed they were serving in Flanders.

Even after the freeze, in early 1573, William's Sea Beggars maintained the supply line by boat under the cover of a thick mist which hung over the lake.

King Philip diverted funds to his Mediterranean campaign against the Ottomans and the Army of Flanders mutinied due to the resultant lack of wages.

[48] Don John of Austria took over the command of the province, attempting to restore some semblance of military discipline but failing to prevent the Sack of Antwerp by mutinous soldiers.

By the time that Alexander Farnese, the future Duke of Parma, took control of the army in 1578, the Low Countries were increasingly split between the rebellious north and those southern provinces still loyal to Spain.

Farnese believed that the Army could hope to cross the Channel in force, relying upon a Catholic uprising in England to support it; instead, Philip decided to undertake a naval attack using the Spanish Armada in 1588.

The Army of Flanders moved against Ostend and Dunkirk in preparations for a follow-up manoeuver across the Channel in support of the Armada, but the defeat of the main naval force brought an end to these plans.

The Dutch continued to consolidate their control over various towns through a sequence of successful sieges, whilst the Army of Flanders saw itself increasingly pointed southwards, against France, being used as a strike force in 1590 and 1592, and fighting to take Doullens, Cambrai (1595) and Calais (1596).

[53] Even with increased taxation, the Low Countries could not hope to support such a force, but funds from Castile were limited – only 300,000 florins arrived each month at the time from Spain.

The Army effectively collapsed, sustaining itself by extorting money and food from the local peoples – widespread fresh Dutch revolts recommenced, accompanied by a general outcry of 'death to the Spaniards'.

[59] The new commander in the Netherlands, Don John of Austria was unable to restore order, resulting in the Sack of Antwerp, a horrific event in which 1,000 houses were destroyed and 8,000 people killed by rampaging soldiers.

When Don John died, Alexander Farnese replaced him as governor and set out to moderate Spanish policy in Catholic Flanders while reducing Protestant outposts by force.

During the Palatinate phase (1618–1625), the Army, 20,000 strong,[62] was sent under Ambrogio Spinola to support the Emperor, pinning down the Protestant Union whilst Saxony intervened against Bohemia.

France and Oxenstierna agreed to a treaty at Hamburg, extending the annual French subsidy of 400,000 riksdalers for three years, but Sweden would not fight against Spain.

Spain had responded to French pressure on Franche-Comté and Catalonia that year by deploying the Army from Flanders, through the Ardennes into northern France, threatening an advance onto Paris.

[71] From 1659, Madrid increasingly relied on the aid of Dutch and English troops to restrain Louis XIV of France's ambitions to annex the Spanish Netherlands (roughly present-day Belgium and Luxembourg), in which Spain showed declining interest after more than a century of war.

[75][3] The Army especially suffered from this, as it could no longer receive adequate numbers of recruits from Spain and Italy due to France having closed the Spanish Road.

[77] With money continuing to be tight, visitors to the provinces in the second half of the century reported seeing the Army in an appalling state, with soldiers begging and short of food.

This stems from an incident in 1585, when during the Battle of Empel, the tercio of Francisco Arias de Bobadilla [es] was trapped on the island of Bommel by the Dutch squadron of Admiral Holako.

One of his soldiers, digging a trench, then discovered a wooden picture of the Immaculate Conception – de Bobadilla placed this on a makeshift altar, and prayed for divine intervention.

Pasar por los bancos de Flandes, – 'to go through the banks of Flanders', refers to overcoming a difficulty, such as the notorious sand-bank protecting the river-strewn Netherlands.