Aromaticity

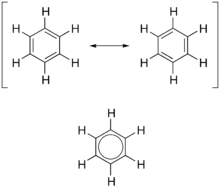

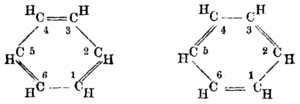

As is standard for resonance diagrams, a double-headed arrow is used to indicate that the two structures are not distinct entities, but merely hypothetical possibilities.

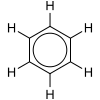

A better representation is that of the circular π bond (Armstrong's inner cycle), in which the electron density is evenly distributed through a π-bond above and below the ring.

The first known use of the word "aromatic" as a chemical term — namely, to apply to compounds that contain the phenyl radical — occurs in an article by August Wilhelm Hofmann in 1855.

[1] If this is indeed the earliest introduction of the term, it is curious that Hofmann says nothing about why he introduced an adjective indicating olfactory character to apply to a group of chemical substances only some of which have notable aromas.

But terpenes and benzenoid substances do have a chemical characteristic in common, namely higher unsaturation indices than many aliphatic compounds, and Hofmann may not have been making a distinction between the two categories.

In the 19th century, chemists found it puzzling that benzene could be so unreactive toward addition reactions, given its presumed high degree of unsaturation.

An explanation for the exceptional stability of benzene is conventionally attributed to Sir Robert Robinson, who was apparently the first (in 1925)[6] to coin the term aromatic sextet as a group of six electrons that resists disruption.

In fact, this concept can be traced further back, via Ernest Crocker in 1922,[7] to Henry Edward Armstrong, who in 1890 wrote "the (six) centric affinities act within a cycle ... benzene may be represented by a double ring (sic) ... and when an additive compound is formed, the inner cycle of affinity suffers disruption, the contiguous carbon-atoms to which nothing has been attached of necessity acquire the ethylenic condition".

Second, he is describing electrophilic aromatic substitution, proceeding (third) through a Wheland intermediate, in which (fourth) the conjugation of the ring is broken.

The circulating π electrons in an aromatic molecule produce ring currents that oppose the applied magnetic field in NMR.

[9] The NMR signal of protons in the plane of an aromatic ring are shifted substantially further down-field than those on non-aromatic sp² carbons.

Aromatic molecules are able to interact with each other in so-called π-π stacking: The π systems form two parallel rings overlap in a "face-to-face" orientation.

For example, cyclooctatetraene (COT) distorts itself out of planarity, breaking π overlap between adjacent double bonds.

The four aromatic amino acids histidine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine each serve as one of the 20 basic building-blocks of proteins.

Further, all 5 nucleotides (adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine, and uracil) that make up the sequence of the genetic code in DNA and RNA are aromatic purines or pyrimidines.

They are extracted from complex mixtures obtained by the refining of oil or by distillation of coal tar, and are used to produce a range of important chemicals and polymers, including styrene, phenol, aniline, polyester and nylon.

A special case of aromaticity is found in homoaromaticity where conjugation is interrupted by a single sp³ hybridized carbon atom.

When carbon in benzene is replaced by other elements in borabenzene, silabenzene, germanabenzene, stannabenzene, phosphorine or pyrylium salts the aromaticity is still retained.

Quite recently, the aromaticity of planar Si56- rings occurring in the Zintl phase Li12Si7 was experimentally evidenced by Li solid state NMR.

A π system with 4n electrons in a flat (non-twisted) ring would be anti-aromatic, and therefore highly unstable, due to the symmetry of the combinations of p atomic orbitals.