Asymmetric hydrogenation

This allows spatial information (what chemists refer to as chirality) to transfer from one molecule to the target, forming the product as a single enantiomer.

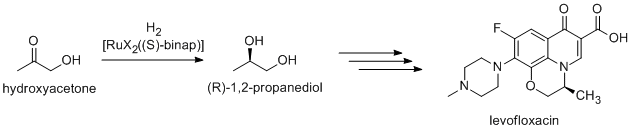

By imitating this process, chemists can generate many novel synthetic molecules that interact with biological systems in specific ways, leading to new pharmaceutical agents and agrochemicals.

The importance of asymmetric hydrogenation in both academia and industry contributed to two of its pioneers — William Standish Knowles and Ryōji Noyori — being collectively awarded one half of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

[2] Later, in 1968, the groups of William Knowles and Leopold Horner independently published the examples of asymmetric hydrogenation using a homogeneous catalysts.

The importance of asymmetric hydrogenation was recognized by the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to William Standish Knowles and Ryōji Noyori.

As such, in most cases dihydrogen is split heterolytically, with the metal acting as a Lewis acid and either an external or internal base "deprotonating" the hydride.

[12] However in both cases, the substrate does not bond directly with the metal centre, thus making it a great example of an outer sphere mechanism.

[18] Asymmetric hydrogenation methods using iron have been realized, although in terms of rates and selectivity, they are inferior to catalysts based on precious metals.

[19] In some cases, structurally ill-defined nanoparticles have proven to be the active species in situ and the modest selectivity observed may result from their uncontrolled geometries.

[31][30][32] Moreover, within a narrowly defined substrate class the performance of metallic complexes with chiral P,N ligands can closely approach perfect conversion and selectivity in systems otherwise very difficult to target.

[33] Certain complexes derived from chelating P-O ligands have shown promising results in the hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated ketones and esters.

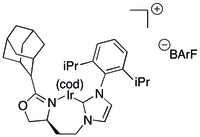

[35][36] NHC-based catalysts featuring a bulky seven-membered metallocycle on iridium have been applied to the catalytic hydrogenation of unfunctionalized olefins[35] and vinyl ether alcohols with conversions and ee's in the high 80s or 90s.

Conversely to the case of olefins, asymmetric hydrogenation of enamines has favoured diphosphine-type ligands; excellent results have been achieved with both iridium- and rhodium-based systems.

[47] A similar system using iridium(I) and a very closely related phosphoramidite ligand is effective for the asymmetric hydrogenation of pyrrolidine-type enamines where the double bond was inside the ring: in other words, of dihydropyrroles.

For example, a consistent system for benzylic aryl imines uses the P,N ligand SIPHOX in conjunction with iridium(I) in a cationic complex to achieve asymmetric hydrogenation with ee >90%.

[52] An efficient catalyst for ketones, (turnover number (TON) up to 4,550,000 and ee up to 99.9%) is an iridium(I) system with a closely related tridentate ligand.

[56] Of these substrates the most consistent success has been seen with nitrogen-containing heterocycles, where the aromatic ring is often activated either by protonation or by further functionalization of the nitrogen (generally with an electron-withdrawing protecting group).

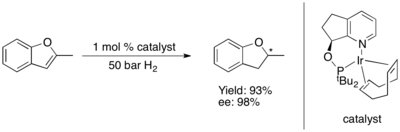

Such strategies are less applicable to oxygen- and sulfur-containing heterocycles, since they are both less basic and less nucleophilic; this additional difficulty may help to explain why few effective methods exist for their asymmetric hydrogenation.

[62] As of October 2012 no mechanism appears to have been proposed, although both the necessity of I2 or a halogen surrogate and the possible role of the heteroaromatic N in assisting reactivity have been documented.

In this case, the authors envision a mechanism where the isoquinoline is alternately protonated in an activating step, then reduced by conjugate addition of hydride from the Hantzsch ester.

Pyridines are highly variable substrates for asymmetric reduction (even compared to other heteroaromatics), in that five carbon centers are available for differential substitution on the initial ring.

Hydrogenating such functionalized pyridines over a number of different heterogeneous metal catalysts gave the corresponding piperidine with the substituents at C3, C4, and C5 positions in an all-cis geometry, in high yield and excellent enantioselectivity.

Methods designed specifically for 2-substituted pyridine hydrogenation can involve asymmetric systems developed for related substrates like 2-substituted quinolines and quinoxalines.

[68] Similarly, chiral Brønsted acid catalysis with a Hantzsh ester as a hydride source is effective for some 2-alkyl pyridines with additional activating substitution.

This system appears to possess superb selectivity (ee > 90%) and perfect diastereoselectivity (all cis) if the substrate has a fused (or directly bound) phenyl ring but yields only racemic product in all other tested cases.

[76] An alternative technique and one that allows more control over the structural and electronic properties of active catalytic sites is the immobilization of catalysts that have been developed for homogeneous catalysis on a heterogeneous support.

[76] The final approach involves the construction of MOFs that incorporate chiral reaction sites from a number of different components, potentially including chiral and achiral organic ligands, structural metal ions, catalytically active metal ions, and/or preassembled catalytically active organometallic cores.

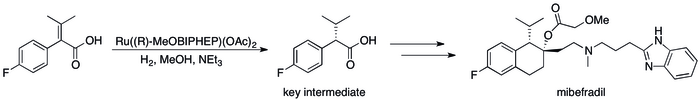

[79] Asymmetric hydrogenation has replaced kinetic resolution based methods has resulted in substantial improvements in the process's efficiency.

[80] Roche's synthesis of mibefradil was likewise improved by replacing resolution with asymmetric hydrogenation, reducing the step count by three and increasing the yield of a key intermediate to 80% from the original 70%.