Asymmetric induction

Asymmetric induction describes the preferential formation in a chemical reaction of one enantiomer (enantioinduction) or diastereoisomer (diastereoinduction) over the other as a result of the influence of a chiral feature present in the substrate, reagent, catalyst or environment.

[clarification needed] Several models exist to describe chiral induction at carbonyl carbons during nucleophilic additions.

The Cram's rule of asymmetric induction named after Donald J. Cram states In certain non-catalytic reactions that diastereomer will predominate, which could be formed by the approach of the entering group from the least hindered side when the rotational conformation of the C-C bond is such that the double bond is flanked by the two least bulky groups attached to the adjacent asymmetric center.

In experiment one 2-phenylpropionaldehyde (1, racemic but (R)-enantiomer shown) was reacted with the Grignard reagent of bromobenzene to 1,2-diphenyl-1-propanol (2) as a mixture of diastereomers, predominantly the threo isomer (see for explanation the Fischer projection).

The first weakness addressed was the statement by Felkin of a strong polar effect in nucleophilic addition transition states, which leads to the complete inversion of stereochemistry by SN2 reactions, without offering justifications as to why this phenomenon was observed.

Incorporation of Bürgi–Dunitz angle[8][9] ideas allowed Anh to postulate a non-perpendicular attack by the nucleophile on the carbonyl center, anywhere from 95° to 105° relative to the oxygen-carbon double bond, favoring approach closer to the smaller substituent and thereby solve the problem of predictability for aldehydes.

Though the Cram and Felkin–Anh models differ in the conformers considered and other assumptions, they both attempt to explain the same basic phenomenon: the preferential addition of a nucleophile to the most sterically favored face of a carbonyl moiety.

One of the most common examples of altered asymmetric induction selectivity requires an α-carbon substituted with a component with Lewis base character (i.e. O, N, S, P substituents).

[13] An example of chelation control of a reaction can be seen here, from a 1987 paper that was the first to directly observe such a "Cram-chelate" intermediate,[14] vindicating the model:

This Newman projection illustrates the Cornforth and Felkin transition state that places the EWG anti- to the incoming nucleophile, regardless of its steric bulk relative to RS and RL.

The improved Felkin–Anh model, as discussed above, makes a more sophisticated assessment of the polar effect by considering molecular orbital interactions in the stabilization of the preferred transition state.

The nucleophile is seen to attack from the less sterically hindered side and anti- to the substituent Rβ, leading to the anti-adduct as the major product.

To make such chelates, the metal center must have at least two free coordination sites and the protecting ligands should form a bidentate complex with the Lewis acid.

The polar benzyloxy group is oriented anti to the carbonyl to minimize dipole interactions and the nucleophile attacks anti- to the bulkier (RM) of the remaining two substituents.

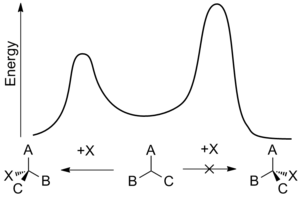

When considering how two functional groups or species react, the precise 3D configurations of the chemical entities involved will determine how they may approach one another.

[25] At this trajectory, attack from the bottom face is disfavored due to steric bulk of the adjacent, large, functional group.

Claude Spino and co-workers[26] have demonstrated significant stereoselectivity improvements upon switching from vinylgrignard to vinylalane reagents with a number of chiral aldehydes.

Chiral auxiliaries may be reversibly attached to the substrate, inducing a diastereoselective reaction prior to cleavage, overall producing an enantioselective process.

Early experiments performed by W. Clark Still[28] and colleagues showed that medium- and large-ring organic molecules can provide striking levels of stereo induction as substrates in reactions such as kinetic enolate alkylation, dimethylcuprate addition, and catalytic hydrogenation.

These studies, among others, helped challenge the widely-held scientific belief that large rings are too floppy to provide any kind of stereochemical control.

En route to (±)-periplanone B,[30] chemists achieved a facial selective epoxidation of an enone intermediate using tert-butyl hydroperoxide in the presence of two other alkenes.

Sodium borohydride reduction of a 10-membered ring enone intermediate en route to the sesquiterpene eucannabinolide[31] proceeded as predicted by molecular modelling calculations that accounted for the lowest energy macrocycle conformation.

Substrate-controlled synthetic schemes have many advantages, since they do not require the use of complex asymmetric reagents to achieve selective transformations.

The TADDOL ligands developed by Dieter Seebach has been used to prepare chiral allyltitanium compounds for asymmetric allylation with aldehydes.

[33] Jim Leighton has developed chiral allysilicon compounds in which the release of ring strain facilitated the stereoselective allylation reaction, 95% to 98% enantiomeric excess could be achieved for a range of achiral aldehydes.