Hydrogen atom

Heavier isotopes of hydrogen are only created artificially in particle accelerators and have half-lives on the order of 10−22 seconds.

The resulting ion, which consists solely of a proton for the usual isotope, is written as "H+" and sometimes called hydron.

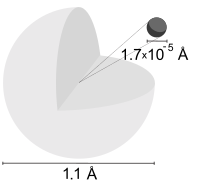

Experiments by Ernest Rutherford in 1909 showed the structure of the atom to be a dense, positive nucleus with a tenuous negative charge cloud around it.

In 1913, Niels Bohr obtained the energy levels and spectral frequencies of the hydrogen atom after making a number of simple assumptions in order to correct the failed classical model.

The assumptions included: Bohr supposed that the electron's angular momentum is quantized with possible values:

Bohr's predictions matched experiments measuring the hydrogen spectral series to the first order, giving more confidence to a theory that used quantized values.

The exact value of the Rydberg constant assumes that the nucleus is infinitely massive with respect to the electron.

Sommerfeld introduced two additional degrees of freedom, allowing an electron to move on an elliptical orbit characterized by its eccentricity and declination with respect to a chosen axis.

This introduced two additional quantum numbers, which correspond to the orbital angular momentum and its projection on the chosen axis.

Thus the correct multiplicity of states (except for the factor 2 accounting for the yet unknown electron spin) was found.

Further, by applying special relativity to the elliptic orbits, Sommerfeld succeeded in deriving the correct expression for the fine structure of hydrogen spectra (which happens to be exactly the same as in the most elaborate Dirac theory).

This is not the case, as most of the results of both approaches coincide or are very close (a remarkable exception is the problem of hydrogen atom in crossed electric and magnetic fields, which cannot be self-consistently solved in the framework of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory), and in both theories the main shortcomings result from the absence of the electron spin.

It was the complete failure of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory to explain many-electron systems (such as helium atom or hydrogen molecule) which demonstrated its inadequacy in describing quantum phenomena.

The Schrödinger equation is the standard quantum-mechanics model; it allows one to calculate the stationary states and also the time evolution of quantum systems.

three independent differential functions appears[6] with A and B being the separation constants: The normalized position wavefunctions, given in spherical coordinates are:

[10] The quantum numbers can take the following values: Additionally, these wavefunctions are normalized (i.e., the integral of their modulus square equals 1) and orthogonal:

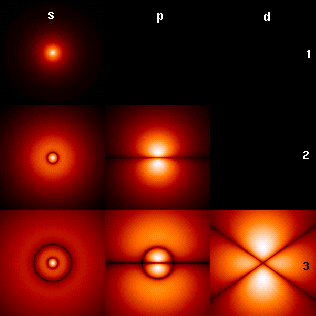

It also yields two other quantum numbers and the shape of the electron's wave function ("orbital") for the various possible quantum-mechanical states, thus explaining the anisotropic character of atomic bonds.

When there is more than one electron or nucleus the solution is not analytical and either computer calculations are necessary or simplifying assumptions must be made.

Since the Schrödinger equation is only valid for non-relativistic quantum mechanics, the solutions it yields for the hydrogen atom are not entirely correct.

This corresponds to the fact that angular momentum is conserved in the orbital motion of the electron around the nucleus.

However, this is a specific property of hydrogen and is no longer true for more complicated atoms which have an (effective) potential differing from the form

The factor in square brackets in the last expression is nearly one; the extra term arises from relativistic effects (for details, see #Features going beyond the Schrödinger solution).

It is worth noting that this expression was first obtained by A. Sommerfeld in 1916 based on the relativistic version of the old Bohr theory.

For all pictures the magnetic quantum number m has been set to 0, and the cross-sectional plane is the xz-plane (z is the vertical axis).

The movement of electrons and change of quantum states radiates light at a frequency of the cosine.

Again the Dirac equation may be solved analytically in the special case of a two-body system, such as the hydrogen atom.

Thus, direct analytical solution of Dirac equation predicts 2S(1/2) and 2P(1/2) levels of hydrogen to have exactly the same energy, which is in a contradiction with observations (Lamb–Retherford experiment).

For these developments, it was essential that the solution of the Dirac equation for the hydrogen atom could be worked out exactly, such that any experimentally observed deviation had to be taken seriously as a signal of failure of the theory.

In the language of Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, the hydrogen atom was first solved by Wolfgang Pauli[15] using a rotational symmetry in four dimensions [O(4)-symmetry] generated by the angular momentum and the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector.

[16] In 1979 the (non-relativistic) hydrogen atom was solved for the first time within Feynman's path integral formulation of quantum mechanics by Duru and Kleinert.