Atomic mass

One dalton is equal to 1⁄12 the mass of a carbon-12 atom in its natural state.

Because substances are usually not isotopically pure, it is convenient to use the elemental atomic mass which is the average (mean) atomic mass of an element, weighted by the abundance of the isotopes.

Although the dalton remains defined via carbon-12, the revision enhances traceability and accuracy in atomic mass measurements.

The atomic mass or relative isotopic mass of each isotope and nuclide of a chemical element is, therefore, a number that can in principle be measured to high precision, since every specimen of such a nuclide is expected to be exactly identical to every other specimen, as all atoms of a given type in the same energy state, and every specimen of a particular nuclide, are expected to be exactly identical in mass to every other specimen of that nuclide.

In the case of many elements that have one naturally occurring isotope (mononuclidic elements) or one dominant isotope, the difference between the atomic mass of the most common isotope, and the (standard) relative atomic mass or (standard) atomic weight can be small or even nil, and does not affect most bulk calculations.

However, such an error can exist and even be important when considering individual atoms for elements that are not mononuclidic.

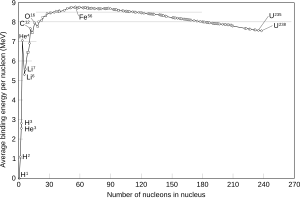

Isotopes of lithium, beryllium, and boron are less strongly bound than helium, as shown by their increasing mass-to-mass number ratios.

At carbon, the ratio of mass (in daltons) to mass number is defined as 1, and after carbon it becomes less than one until a minimum is reached at iron-56 (with only slightly higher values for iron-58 and nickel-62), then increases to positive values in the heavy isotopes, with increasing atomic number.

This corresponds to the fact that nuclear fission in an element heavier than zirconium produces energy, and fission in any element lighter than niobium requires energy.

On the other hand, nuclear fusion of two atoms of an element lighter than scandium (except for helium) produces energy, whereas fusion in elements heavier than calcium requires energy.

The fusion of two atoms of 4He yielding beryllium-8 would require energy, and the beryllium would quickly fall apart again.

4He can fuse with tritium (3H) or with 3He; these processes occurred during Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

The formation of elements with more than seven nucleons requires the fusion of three atoms of 4He in the triple-alpha process, skipping over lithium, beryllium, and boron to produce carbon-12.

The first scientists to determine relative atomic masses were John Dalton and Thomas Thomson between 1803 and 1805 and Jöns Jakob Berzelius between 1808 and 1826.

Berzelius, however, soon proved that this was not even approximately true, and for some elements, such as chlorine, relative atomic mass, at about 35.5, falls almost exactly halfway between two integral multiples of that of hydrogen.

In the 1860s, Stanislao Cannizzaro refined relative atomic masses by applying Avogadro's law (notably at the Karlsruhe Congress of 1860).

He formulated a law to determine relative atomic masses of elements: the different quantities of the same element contained in different molecules are all whole multiples of the atomic weight and determined relative atomic masses and molecular masses by comparing the vapor density of a collection of gases with molecules containing one or more of the chemical element in question.

[11] In the 20th century, until the 1960s, chemists and physicists used two different atomic-mass scales.

The chemists used an "atomic mass unit" (amu) scale such that the natural mixture of oxygen isotopes had an atomic mass 16, while the physicists assigned the same number 16 to only the atomic mass of the most common oxygen isotope (16O, containing eight protons and eight neutrons).

However, because oxygen-17 and oxygen-18 are also present in natural oxygen this led to two different tables of atomic mass.

This shift in nomenclature reaches back to the 1960s and has been the source of much debate in the scientific community, which was triggered by the adoption of the unified atomic mass unit and the realization that weight was in some ways an inappropriate term.