Ideal gas law

It is a good approximation of the behavior of many gases under many conditions, although it has several limitations.

[1] The ideal gas law is often written in an empirical form:

It can also be derived from the microscopic kinetic theory, as was achieved (apparently independently) by August Krönig in 1856[2] and Rudolf Clausius in 1857.

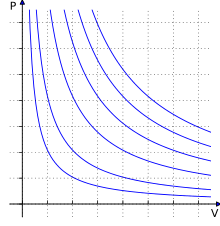

[3] The state of an amount of gas is determined by its pressure, volume, and temperature.

The chemical amount, n (in moles), is equal to total mass of the gas (m) (in kilograms) divided by the molar mass, M (in kilograms per mole): By replacing n with m/M and subsequently introducing density ρ = m/V, we get: Defining the specific gas constant Rspecific as the ratio R/M, This form of the ideal gas law is very useful because it links pressure, density, and temperature in a unique formula independent of the quantity of the considered gas.

Alternatively, the law may be written in terms of the specific volume v, the reciprocal of density, as It is common, especially in engineering and meteorological applications, to represent the specific gas constant by the symbol R. In such cases, the universal gas constant is usually given a different symbol such as

[5] In statistical mechanics, the following molecular equation (i.e. the ideal gas law in its theoretical form) is derived from first principles: where p is the absolute pressure of the gas, n is the number density of the molecules (given by the ratio n = N/V, in contrast to the previous formulation in which n is the number of moles), T is the absolute temperature, and kB is the Boltzmann constant relating temperature and energy, given by: where NA is the Avogadro constant.

The form can be furtherly simplified by defining the kinetic energy corresponding to the temperature: so the ideal gas law is more simply expressed as: From this we notice that for a gas of mass m, with an average particle mass of μ times the atomic mass constant, mu, (i.e., the mass is μ Da) the number of molecules will be given by and since ρ = m/V = nμmu, we find that the ideal gas law can be rewritten as In SI units, p is measured in pascals, V in cubic metres, T in kelvins, and kB = 1.38×10−23 J⋅K−1 in SI units.

When comparing the same substance under two different sets of conditions, the law can be written as According to the assumptions of the kinetic theory of ideal gases, one can consider that there are no intermolecular attractions between the molecules, or atoms, of an ideal gas.

This corresponds to the kinetic energy of n moles of a monoatomic gas having 3 degrees of freedom; x, y, z.

Also, the property for which the ratio is known must be distinct from the property held constant in the previous column (otherwise the ratio would be unity, and not enough information would be available to simplify the gas law equation).

Under these conditions, p1V1γ = p2V2γ, where γ is defined as the heat capacity ratio, which is constant for a calorifically perfect gas.

In internal combustion engines γ varies between 1.35 and 1.15, depending on constitution gases and temperature.

In the case of free expansion for an ideal gas, there are no molecular interactions, and the temperature remains constant.

For real gasses, the molecules do interact via attraction or repulsion depending on temperature and pressure, and heating or cooling does occur.

For reference, the Joule–Thomson coefficient μJT for air at room temperature and sea level is 0.22 °C/bar.

Since the ideal gas law neglects both molecular size and intermolecular attractions, it is most accurate for monatomic gases at high temperatures and low pressures.

The neglect of molecular size becomes less important for lower densities, i.e. for larger volumes at lower pressures, because the average distance between adjacent molecules becomes much larger than the molecular size.

More detailed equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, account for deviations from ideality caused by molecular size and intermolecular forces.

are constants in this context because of each equation requiring only the parameters explicitly noted in them changing.

Keeping this in mind, to carry the derivation on correctly, one must imagine the gas being altered by one process at a time (as it was done in the experiments).

Say, starting to change only pressure and volume, according to Boyle's law (Equation 1), then: After this process, the gas has parameters

Using then equation (6) to change the pressure and the number of particles, After this process, the gas has parameters

The ideal gas law can also be derived from first principles using the kinetic theory of gases, in which several simplifying assumptions are made, chief among which are that the molecules, or atoms, of the gas are point masses, possessing mass but no significant volume, and undergo only elastic collisions with each other and the sides of the container in which both linear momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

First we show that the fundamental assumptions of the kinetic theory of gases imply that Consider a container in the

When a molecule bounces off the wall of the container, it changes its momentum

The magnitude of the change of momentum of all molecules that bounce off the area

Now we consider a situation where they can move with different velocities, so we apply an "averaging transformation" to the above equation, effectively replacing

The root-mean-square speed can be calculated by Using the integration formula it follows that from which we get the ideal gas law: Let q = (qx, qy, qz) and p = (px, py, pz) denote the position vector and momentum vector of a particle of an ideal gas, respectively.

Then (two times) the time-averaged kinetic energy of the particle is: where the first equality is Newton's second law, and the second line uses Hamilton's equations and the equipartition theorem.