Axial twist theory

axial twist hypothesis) is a scientific theory that has been proposed to explain a range of unusual aspects of the body plan of vertebrates (including humans).

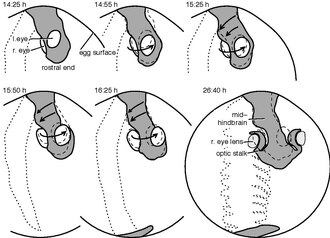

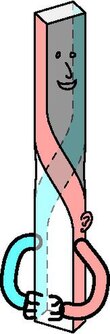

Phenomena the theory can explain include: According to the axial twist developmental model, the anterior part of the head turns against the rest of the body, except for the inner organs.

Due to this twist, the forebrain and face are turned around such that left and right, but also anterior and posterior are flipped in the adult vertebrate.

In the end of the 19th century, the famous neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal proposed a theory to explain the contralateral organization of the forebrain that was rapidly and widely accepted.

[12] On the other hand, the surface cells of the hind side of the head moved to the left, consistent with an axial twist.

It is now well established, that the Nodal signaling cascade and the right-to-left flow produced by ciliated cells in the primitive streak are central in setting up the asymmetric organization.

According to the axial twist theory, this represents an extreme case of Yakovlevian torque,[18] and may occur when the cerebrum does not turn during early embryology.

[19] According to the axial twist model, the two nervous systems could not turn due to the complex configuration of the body and therefore remained on either side.

[1] The axial twist is thought to have evolved in a common ancestor of all vertebrates, but the mechanism remains speculative.

[1] de Lussanet et al. posit two possible evolutionary origins: one, that an ancestral vertebrate turned to its left side during the transition from a free-swimming larva to a bottom-feeding adult stage, like modern-day flatfishes.

This second hypothesis would connect to the lifecycle of the closely related Cephalochordata, which have a mouth that is initially on the left side before moving to ventral position but lack an axial twist.

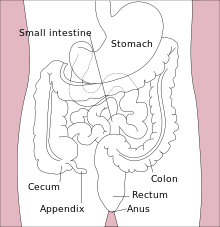

[1] Even the most distant clades of vertebrates – the agnathan lampreys and hagfish – possess an optic chiasm and contralateral brain organization,[20] as well as a left-sided heart and asymmetric bowels.

[20] Fossil skull impressions of early vertebrates from the Ordovician and later show the presence of an optic chiasm.

[1][23][5] The forebrain (cerebrum and thalamus) predominantly represents the opposite side of the body (and the visual world).

However, motor control usually requires information from both sides of the body, and so the contralateral representation is by no means absolute.

[25] Thus, the Yakovlevian torque and the spinal asymmetry are in opposite direction, just as predicted by the axial twist theory.

[20] Thus, motor, somatosensory, auditory, and visual primary regions in the forebrain predominantly represent the contralateral side of the body.

[citation needed] Most afferent and efferent connections of the forebrain have bilateral components, especially outside the primary sensory and motor regions.

The branch towards the LGN exists only in tetrapods[29] and is therefore generally understood as acquired later in the evolution of vertebrates and thus makes an exception.

The abducens nerve innervates the lateral rectus muscle of the eye in most vertebrates, except lampreys and hagfishes.

[citation needed] The aurofacial asymmetry expresses the position of the face (eyes, nose, mouth) with respect to the plane perpendicular to the axis through the ears.

[17][32] The question of why the heart should have a left-sided orientation, has been topic of scientific research before the axial twist theory was published, but none of the hypotheses could stand critical testing.

[35][36] As explained above, Marcel Kinsbourne proposed that the body (soma) but not the anterior head is inverted (hence somatic twist hypothesis).

There is no other theory to explain the left position of the heart or the asymmetric orientation of the bowels and related organs.

[24] The parcellation theory proposes that an increasing brain size can conserve coincidental contralateral organization,[26] but does not explain the optic chiasm, nor that most vertebrates have a rather small forebrain, especially the early forms.

[1][2][23][5] Although a considerable volume of research exists on the genetic and embryological mechanisms of asymmetric development, an open question is how the twist is initiated and how the inversion of the left-right and up-down axes in the anterior head region is established.

[citation needed] It has been proposed that problems in the axial twist development may play a central role in developmental malformations such as holoprosencephaly[1] and skoliosis[5] but these have not been looked into.