Mutationism

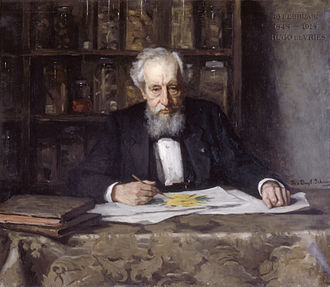

In 1901 the geneticist Hugo de Vries gave the name "mutation" to seemingly new forms that suddenly arose in his experiments on the evening primrose Oenothera lamarckiana.

In the first decade of the 20th century, mutationism, or as de Vries named it mutationstheorie, became a rival to Darwinism supported for a while by geneticists including William Bateson, Thomas Hunt Morgan, and Reginald Punnett.

Understanding of mutationism is clouded by the mid-20th century portrayal of the early mutationists by supporters of the modern synthesis as opponents of Darwinian evolution and rivals of the biometrics school who argued that selection operated on continuous variation.

However, the alignment of Mendelian genetics and natural selection began as early as 1902 with a paper by Udny Yule, and built up with theoretical and experimental work in Europe and America.

[5] In 1822, in the second volume of his Philosophie anatomique, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire endorsed a theory of saltational evolution that "monstrosities could become the founding fathers (or mothers) of new species by instantaneous transition from one form to the next.

[14][15] William Bateson's 1894 book Materials for the Study of Variation, Treated with Especial Regard to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species marked the arrival of mutationist thinking, before the rediscovery of Mendel's laws.

[16] He examined discontinuous variation (implying a form of saltation[17]) where it occurred naturally, following William Keith Brooks, Galton, Thomas Henry Huxley and St. George Jackson Mivart.

[c][20][21] By this, de Vries meant that a new form of the plant was created in a single step (not the same as a mutation in the modern sense); no long period of natural selection was required for speciation, and nor was reproductive isolation.

[22] In the view of the historian of science Peter J. Bowler, De Vries used the term to mean[1] large-scale genetic changes capable of producing a new subspecies, or even species, instantaneously.

[1]The historian of science Betty Smocovitis described mutationism as:[2] the case of purported saltatory evolution that Hugo de Vries had mistakenly interpreted for the evening primrose, Oenothera.

It showed, too, that Mendelian inheritance had no essential link with mutationism: Fisher stressed that small variations (per gene) would be sufficient for natural selection to drive evolution.

Fisher argued that selection acting on genes making small modifications to the butterfly's phenotype (its appearance) would allow the multiple forms of a polymorphism to be established.

[47] In his 1940 book The Material Basis of Evolution, the German geneticist Richard Goldschmidt argued for single-step speciation by macromutation, describing the organisms thus produced as "hopeful monsters".

Reviewing the history of macroevolutionary theories, the American evolutionary biologist Douglas J. Futuyma notes that since 1970, two very different alternatives to Darwinian gradualism have been proposed, both by Stephen Jay Gould: mutationism, and punctuated equilibria.

[70] Futuyma concludes, following other biologists reviewing the field such as K.Sterelny[71] and A. Minelli,[72] that essentially all the claims of evolution driven by large mutations could be explained within the Darwinian evolutionary synthesis.

[74] A 2019 review by Svensson and David Berger concluded that "we find little support for mutation bias as an independent force in adaptive evolution, although it can interact with selection under conditions of small population size and when standing genetic variation is limited, entirely consistent with standard evolutionary theory.

"[75] In contrast to Svensson and Berger a 2023 review by Arlin Stoltzfus and colleagues concluded that there is strong empirical evidence and theoretical arguments that mutation bias has predictable effects on genetic changes fixed in adaptation.

Large mutations looked likely to drive evolution quickly, and avoided the difficulty which had rightly worried Darwin, namely that blending inheritance would average out any small favourable changes.

In this version, little progress was made during the eclipse of Darwinism, and the debate between mutationist geneticists such as de Vries and biometricians such as Pearson ended with the victory of the modern synthesis between about 1918 and 1950.

[80][81] According to this account, the new population genetics of the 1940s demonstrated the explanatory power of natural selection, while mutationism, alongside other non-Darwinian approaches such as orthogenesis and structuralism, was essentially abandoned.

[83] A more recent view, advocated by the historians Arlin Stoltzfus and Kele Cable, is that Bateson, de Vries, Morgan and Punnett had by 1918 formed a synthesis of Mendelism and mutationism.

The understanding achieved by these geneticists spanned the action of natural selection on alleles (alternative forms of a gene), the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, the evolution of continuously-varying traits (like height), and the probability that a new mutation will become fixed.

In this view, the early geneticists accepted natural selection alongside mutation, but rejected Darwin's non-Mendelian ideas about variation and heredity, and the synthesis began soon after 1900.