Baeyer–Villiger oxidation

[5] This migration step is also (at least in silico) assisted by two or three peroxyacid units enabling the hydroxyl proton to shuttle to its new position.

[9] Keeping this structure in mind, it makes sense that the substituent that can maintain positive charge the best would be most likely to migrate.

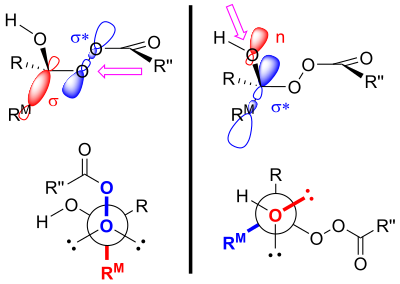

[16] These three reaction mechanisms can really be split into two pathways of peroxyacid attack – on either the oxygen or the carbon of the carbonyl group.

[17] In 1953, William von Eggers Doering and Edwin Dorfman elucidated the correct pathway for the reaction mechanism of the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation by using oxygen-18-labelling of benzophenone.

[22] In 1962, G. B. Payne reported that the use of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a selenium catalyst will produce the epoxide from alkenyl ketones, while use of peroxyacetic acid will form the ester.

[24] The use of hydrogen peroxide as an oxidant would be advantageous, making the reaction more environmentally friendly as the sole byproduct is water.

[7] Benzeneseleninic acid derivatives as catalysts have been reported to give high selectivity with hydrogen peroxide as the oxidant.

[26] Among stannosilicates, particularly the zeotype Sn-beta and the amorphous Sn-MCM-41 show promising activity and close to full selectivity towards the desired product.

[23] In nature, enzymes called Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs) perform the oxidation analogously to the chemical reaction.

[30] In the catalytic cycle (see figure on the right), the cellular redox equivalent NADPH first reduces the cofactor, which allows it subsequently to react with molecular oxygen.

[34] BVMOs have been widely studied due to their potential as biocatalysts, that is, for an application in organic synthesis.

[29] BVMOs in particular are interesting for application because they fulfil a range of criteria typically sought for in biocatalysis: besides their ability to catalyse a synthetically useful reaction, some natural homologs were found to have a very large substrate scope (i.e. their reactivity was not restricted to a single compound, as often assumed in enzyme catalysis),[36] they can be easily produced on a large scale, and because the three-dimensional structure of many BVMOs has been determined, enzyme engineering could be applied to produce variants with improved thermostability and/or reactivity.

[29][35] Zoapatanol is a biologically active molecule that occurs naturally in the zeopatle plant, which has been used in Mexico to make a tea that can induce menstruation and labor.

[40][41] They used the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation to make a lactone that served as a crucial building block that ultimately led to the synthesis of zoapatanol.

[40][41] In 2013, Alina Świzdor reported the transformation of the steroid dehydroepiandrosterone to anticancer agent testololactone by use of a Baeyer–Villiger oxidation induced by fungus that produces Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases.