Balarama

[13][14] Balarama is an ancient deity, a prominent one by the epics era of Indian history as evidenced by archeological and numismatic evidence.

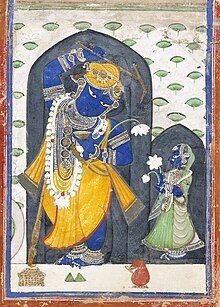

His iconography appears with Nāga (many-headed serpent), a plough and other farm artifacts such as a watering pot, possibly indicating his origins in a bucolic, agricultural culture.

[17] However, Balarama's mythology and his association with the ten avatars of Vishnu is relatively younger and post-Vedic, because it is not found in the Vedic texts.

In some art works of the Vijayanagara Empire, temples of Gujarat and elsewhere, for example, Baladeva is the eighth avatar of Vishnu, prior to the Buddha (Buddhism) or Arihant (Jainism).

[19][20] Balarama finds a mention in Kautilya's Arthashastra (4th to 2nd century BCE), where according to Hudson, his followers are described as "ascetic worshippers" with shaved heads or braided hair.

[27] Coins dated to about 185-170 BCE belonging to the Indo-Greek King Agathocles show Balarama's iconography and Greek inscriptions.

At Chilas II archeological site dated to the first half of 1st-century CE in northwest Pakistan, near Afghanistan border, are engraved two males along with many Buddhist images nearby.

The artwork also has an inscription with it in Kharosthi script, which has been deciphered by scholars as Rama-Krsna, and interpreted as an ancient depiction of the two brothers Balarama and Krishna.

[39] The earliest surviving southeast Asian artwork related to Balarama is from the Phnom Da collection, near Angkor Borei in Cambodia's lower Mekong Delta region.

The evil king Kamsa, the tyrant of Mathura, was intent upon killing the children of his cousin, Devaki, because of a prophecy that he would die at the hands of her eighth child.

Balarama grew up with his younger brother Krishna with his foster-parents, in the household of the head of cowherds Nanda, and his wife, Yashoda.

[9] The chapter 10 of the Bhagavata Purana describes it as follows: The Bhagavan as the Self of everything tells the creative power of His unified consciousness (yogamaya) about His plan for His own birth as Balarama and Krishna.

[50] In the Bhagavata Purana, it is described that after Balarama took part in the battle causing the destruction of the remainder of the Yadu dynasty and witnessing the disappearance of Krishna, he sat down in a meditative state and departed from this world.

[51] Some scriptures describe a great white snake that left the mouth of Balarama, in reference to his identity as Ananta-Sesha, a form of Vishnu.

In Hindu tradition, Balarama is depicted as a farmer's patron deity, signifying the one who is "harbinger of knowledge", of agricultural tools and prosperity.

[52] He is almost always shown and described with Krishna, such as in the act of stealing butter, playing childhood pranks, complaining to Yashoda that his baby brother Krishna had eaten dirt, playing in cow sheds, studying together at the school of guru Sandipani, and fighting malevolent beasts sent by Kamsa to kill the two brothers.

[52][53] In the classical Tamil work Akananuru, Krishna hides from Balarama when he steals the clothes of the milkmaids while they bathe, suggesting his brother's vigilance.

[59][60] The Jain Puranas, notably, the Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacarita of Hemachandra, narrate hagiographical accounts of nine Baladevas or Balabhadras who are believed to be śalākāpuruṣas (literally torch-bearers, great personalities).

[65] The stories of these triads can be found in the Harivamsa Purana (8th century CE) of Jinasena (not be confused with its namesake, the addendum to Mahābhārata) and the Trishashti-shalakapurusha-charita of Hemachandra.

[69] For example, Krishna loses battles in the Jain versions, and his gopis and his clan of Yadavas die in a fire created by an ascetic named Dvaipayana.

Similarly, after dying from the hunter Jara's arrow, the Jaina texts state Krishna goes to the third hell in Jain cosmology, while Balarama is said to go to the sixth heaven.

[71] Evidence related to early Jainism, states Patrick Olivelle and other scholars, suggests Balarama had been a significant farmer deity in Jain tradition in parts of the Indian subcontinent such as near the Mathura region.