Battle of Britain

The last was under Hugh Dowding, who opposed the doctrine that bombers were unstoppable: the invention of radar at that time could allow early detection, and prototype monoplane fighters were significantly faster.

"[38][39] When war commenced, Hitler and the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or "High Command of the Armed Forces") issued a series of directives ordering, planning and stating strategic objectives.

6" planned the offensive to defeat these allies and "win as much territory as possible in the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France to serve as a base for the successful prosecution of the air and sea war against England".

[47][62] In November 1939, the OKW reviewed the potential for an air- and seaborne invasion of Britain: the Kriegsmarine was faced with the threat the Royal Navy's larger Home Fleet posed to a crossing of the English Channel, and together with the German Army viewed control of airspace as a necessary precondition.

By mid-1940, all RAF Spitfire and Hurricane fighter squadrons converted to 100 octane aviation fuel,[78] which allowed their Merlin engines to generate significantly more power and an approximately 30 mph increase in speed at low altitudes[79][80] through the use of an Emergency Boost Override.

[99] Although it had been successful in previous Luftwaffe engagements, the Stuka suffered heavy losses in the Battle of Britain, particularly on 18 August, due to its slow speed and vulnerability to fighter interception after dive-bombing a target.

As the losses went up Stuka units, with limited payload and range in addition to their vulnerability, were largely removed from operations over England and diverted to concentrate on shipping, until eventually re-deployed to the Eastern Front in 1941.

[8][115] These included 145 Poles, 127 New Zealanders, 112 Canadians, 88 Czechoslovaks, 10 Irish, 32 Australians, 28 Belgians, 25 South Africans, 13 French, 9 Americans, 3 Southern Rhodesians and individuals from Jamaica, Barbados and Newfoundland.

[118][119][120][121] "Had it not been for the magnificent material contributed by the Polish squadrons and their unsurpassed gallantry," wrote Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, head of RAF Fighter Command, "I hesitate to say that the outcome of the Battle would have been the same.

In addition, Luftwaffe aircraft were equipped with life rafts and the aircrew were provided with sachets of a chemical called fluorescein which, on reacting with water, created a large, easy-to-see, bright green patch.

In action, the Luftwaffe believed from their pilot claims and the impression given by aerial reconnaissance that the RAF was close to defeat, and the British made strenuous efforts to overcome the perceived advantages held by their opponents.

According to F. W. Winterbotham, who was the senior Air Staff representative in the Secret Intelligence Service,[166] Ultra helped establish the strength and composition of the Luftwaffe's formations, the aims of the commanders[167] and provided early warning of some raids.

The intensive raids and destruction wrought during the Blitz damaged both Dowding and Park in particular, for the failure to produce an effective night-fighter defence system, something for which the influential Leigh-Mallory had long criticised them.

After the initial disasters of the war, with Vickers Wellington bombers shot down in large numbers attacking Wilhelmshaven and the slaughter of the Fairey Battle squadrons sent to France, it became clear that they would have to operate mainly at night to avoid incurring very high losses.

Although most of these raids were unproductive, there were some successes; on 1 August, five out of twelve Blenheims sent to attack Haamstede and Evere (Brussels) were able to destroy or heavily damage three Bf 109s of II./JG 27 and apparently kill a Staffelkapitän identified as a Hauptmann Albrecht von Ankum-Frank.

One Blenheim returned early (the pilot was later charged and due to appear before a court martial, but was killed on another operation); the other eleven, which reached Denmark, were shot down, five by flak and six by Bf 109s.

[203] The attacks were widespread: over the night of 30 June alarms were set off in 20 counties by just 20 bombers, then next day the first daylight raids were carried out during 1 July, on both Hull in Yorkshire and Wick, Caithness.

[citation needed] On the afternoon of 15 August, Hauptmann Walter Rubensdörffer leading Erprobungsgruppe 210 mistakenly bombed Croydon airfield (on the outskirts of London) instead of the intended target, RAF Kenley.

Overnight on 22/23 August, the output of an aircraft factory at Filton near Bristol was drastically affected by a raid in which Ju 88 bombers dropped over 16 long tons (16 t) of high explosive bombs.

London was on red alert over the night of 28/29 August, with bombs reported in Finchley, St Pancras, Wembley, Wood Green, Southgate, Old Kent Road, Mill Hill, Ilford, Chigwell and Hendon.

[230] In preparation, detailed target plans under the code name Operation Loge for raids on communications, power stations, armaments works and docks in the Port of London were distributed to the Fliegerkorps in July.

[231] On 3 September Göring planned to bomb London daily, with General Albert Kesselring's enthusiastic support, having received reports the average strength of RAF squadrons was down to five or seven fighters out of twelve and their airfields in the area were out of action.

[242] The Messerschmitt Bf 109E-7 corrected this deficiency by adding a ventral centre-line ordnance rack to take either an SC 250 bomb or a standard 300-litre Luftwaffe drop tank to double the range to 1,325 km (820 mi).

General Hans Jeschonnek, Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, begged for a last chance to defeat the RAF and for permission to launch attacks on civilian residential areas to cause mass panic.

Henceforth, in the face of mounting losses in men, aircraft and the lack of adequate replacements, the Luftwaffe completed their gradual shift from daylight bomber raids and continued with nighttime bombing.

[185] During the battle, and for the rest of the war, an important factor in keeping public morale high was the continued presence in London of King George VI and his wife Queen Elizabeth.

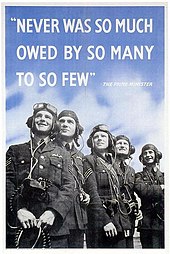

[276] The place of the Battle of Britain in British popular memory partly stems from the Air Ministry's successful propaganda campaign from July to October 1940, and its praise of the defending fighter pilots from March 1941 onwards.

[278] For the RAF, Fighter Command had achieved a great victory in successfully carrying out Sir Thomas Inskip's 1937 air policy of preventing the Germans from knocking Britain out of the war.

[283] Richard Evans writes: Irrespective of whether Hitler was really set on this course, he simply lacked the resources to establish the air superiority that was the sine qua non [prerequisite] of a successful crossing of the English Channel.

On this day in 1940, the Luftwaffe embarked on their largest bombing attack yet, forcing the engagement of the entirety of the RAF in defence of London and the South East, which resulted in a decisive British victory that proved to mark a turning point in Britain's favour.