Battle of Capo d'Orso

Despite some important initial successes such as the sack of Rome in 1527, the Spanish army was quickly disintegrating due to a dramatic lack of funding.

By the end of 1527, a French army under the viscount of Lautrec was moving southwards from Central Italy, capturing cities one by one and rapidly pushing the Spaniards out of their prized possession in the region, the Kingdom of Naples.

If the city of Naples were to fall into French hands, Charles V would lose his last foothold in the peninsula and France would become the dominating power in the central Mediterranean.

The city was well defended and attempts to seize it by force by land and sea were pushed back, and a real siege began.

The French cut the aqueducts bringing fresh water to Naples and, as the city had but a few wells, thirst quickly became a problem for the besieged.

The patrols of the French navy prevented the arrival of supplies from Sicily – two ships carrying wheat for the besieged Neapolitans were intercepted by Filippino Doria mid-April.

[6] But the Venetians were delayed by the sore state of their galleys and several operations against Spanish strongholds in Apulia such as Monopoli, Otranto, and Lecce.

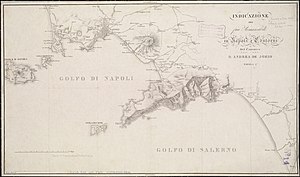

For instance, hoping to go unnoticed and to be able to land in Gaeta or Castellammare where they could use the windmills to grind their grain into flour, the Spanish fleet took to the sea in the morning of April 27.

Historian Maurizio Arfaioli hypothesizes that the choice may have been the result of a power play within the Spanish high-command as Hugo de Moncada, veteran of many campaigns in the Mediterranean, saw a naval operation as the best chance to counter the prominence of the young Philibert of Chalon, Prince of Orange, a brilliant general but who had never fought on the sea.

[11] The squabble of the Spanish generals led to the designation of a third man as the chief of the flotilla: Alfonso d'Avalos, marchese del Vasto,[12] but nonetheless don Hugo joined the fleet, albeit not as its main commander, while Philipert de Chalon remained in Naples.

Aware of the greater seamanship of the Genoese, the Spaniards decided to fill their galleys with "chosen troops" to guarantee their superiority during the hand-to-hand phase of the combat, once ships were locked one with the other and boarding parties sent onto the enemy's vessels.

Steps were also taken to ensure the loyalty of the Genoese navy officers and sailors serving on the Neapolitan squadron as the Spaniards were to be confronted by a French fleet heavily manned by their fellow countrymen.

The commander of the Neapolitan squadron, Fabrizio Giustiniani, in particular, was suspected as he happened to be the father-in-law of Antonio Doria, one of the main mercenaries serving on the French side.

[15] On the evening of April 27, the Spanish fleet exited anew the port of Naples and sailed westwards one and half nautical mile to Posillipo just outside the city walls and spent the night there.

Several authors of the time mention that once in Capri, the Spanish officers of the Spanish fleet lunched leisurely (Hugo de Moncada had apparently brought musicians with him) and the men listened to a protracted sermon by Portuguese hermit Gonsalvo Baretta (who enticed them to fight the Genoese, qualified of "white Moors").

[45][46] The Spanish fleet left Capri in the afternoon, overtook the Punta della Campanella [it] and proceeds due East towards Amalfi.

At 4:00PM, some 300 Gascon musketeers under the command of Gilbert du Croq[47] arrive at Vietri and are hastidly embarked on wehe galleys to complement the Genoese marines.

[48][49] With dozens of vessels, the Spanish fleets looked very impressive and three French ships – the Nettuna, the Segnora, and the Mora – broke formation and escaped southward.

[58] Meanwhile, on the southern flank, the German landsknechts aboard the Spanish galleys Perpignana and Calabresa also reached close-quarter combat with the French vessels Fortuna and Sirena.

But, while the battle wes raging, the three French ships which had broken formation earlier changed path and returned to the fight.

To tip the scales in his favour, Filippino Doria freed the rowers, the ciurma, made of delinquents, criminals, and Muslim captives from their chains and promised their freedom if they fight for him.

Fabrizio Giustiniani, "il Gobbo" was wounded and out-of-combat and the Neapolitan captain Cesare Fieramosca, in charge of the infantry, was thrown into the sea by a direct hit.

Angered by what he considered as cowardice, the Prince of Orange had all the officers of the ship, including its captain, the Catalan Francès de Loria, immediately hanged in full view of the harbour.

[69][a] Understanding what awaited him, Orazio, the captain of the second galley decided not to return to Naples and headed Westwards with its French prisoners aboard and disappeared in the dark.

[89] Pope Clement saw the Spanish defeat as a just punishment for those who had sacked the Holy City a year prior, declaring: "the immortal God has not been a hesitant and tardy avenger of this infamous crime"[90] The siege of Naples continued on land as well as on sea.

There seems however to exist a long poem composed by a participant to the battle, Ludovico di Lorenzo Martelli, describing the engagement, written during the poet's three-month captivity in Genoa.