Gallipoli campaign

[16][17][18] On 29 October 1914, two former German warships, the Ottoman Yavûz Sultân Selîm and Midilli, conducted the Black Sea raid, in which they bombarded the Russian port of Odessa and sank several ships.

[35] Frustrated by the mobility of the Ottoman batteries, sited on the instructions of General Otto Liman von Sanders, which evaded the Entente bombardments and threatened the minesweepers sent to clear the Straits, Churchill pressed the naval commander, Admiral Sackville Carden, to increase the fleet's efforts.

[38] On the morning of 18 March 1915, the Entente fleet, comprising 18 battleships with an array of cruisers and destroyers, began the main attack against the narrowest point of the Dardanelles, where the straits are 1 mi (1.6 km) wide.

Some of the senior naval officers like the commander of Queen Elizabeth, Commodore Roger Keyes, felt that they had come close to victory, believing that the Ottoman guns had almost run out of ammunition but the views of de Robeck, the First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher and others prevailed.

[52] The naïveté of the Entente planners was illustrated by a leaflet that was issued to the British and Australians while they were still in Egypt, Turkish soldiers as a rule manifest their desire to surrender by holding their rifle butt upward and by waving clothes or rags of any colour.

[69][70] Sanders considered Besika Bay on the Asiatic coast to be the most likely invasion site, since the terrain was easier to cross and was convenient to attack the most important Ottoman batteries guarding the straits; a third of the 5th Army was assembled there.

[75][76] Sanders was certain that a rigid system of defence would fail and that the only hope of success lay in the mobility of the three groups, particularly the 19th Division near Boghali, in general reserve, ready to move to Bulair, Gaba Tepe or the Asiatic shore.

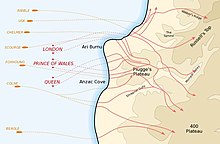

The ANZACs, with the 3rd Australian Infantry Brigade spearheading the assault, were to land north of Gaba Tepe on the Aegean coast, from where they could advance across the peninsula, cut off the Ottoman troops in Kilitbahir and stop reinforcements from reaching Cape Helles.

As landings began at Cape Helles and ANZAC Cove at dawn on 25 April, AE2 reached Chanak by 6:00 a.m. and torpedoed an Ottoman gunboat believed to be a Peyk-i Şevket-class cruiser then evaded a destroyer.

[98] Stoker was ordered to "generally run amok" and, with no enemies in sight, he sailed into the Sea of Marmara, where AE2 cruised for five days to give the impression of greater numbers and made several attacks against Ottoman ships, which failed because of mechanical problems with the torpedoes.

The covering force of Royal Munster Fusiliers and Hampshires landed from a converted collier, SS River Clyde, which was run aground beneath the fortress so that the troops could disembark along ramps.

[101] On 27 April, HMS E14 (Lieutenant Commander Edward Boyle), entered the Sea of Marmara on a three-week patrol, which became one of the most successful Entente naval actions of the campaign, in which four ships were sunk, including the transport Gul Djemal which was carrying 6,000 troops and a field battery to Gallipoli.

[128][127] The Australians lost a number of officers to sniping, including the commander of the 1st Division, Major General William Bridges, who was wounded while inspecting a 1st Light Horse Regiment position near "Steele's Post" and died of his injuries on the hospital ship HMHS Gascon on 18 May.

[135] The British advantage in naval artillery diminished after the battleship HMS Goliath was torpedoed and sunk on 13 May by the Muâvenet-i Millîye, killing 570 men out of a crew of 750, including the ship's commander, Captain Thomas Shelford.

[139] The submarine HMS E11 (Lieutenant Commander Martin Nasmith, later awarded a Victoria Cross) passed through the Dardanelles on 18 May and sank or disabled eleven ships, including three on 23 May, before entering Constantinople Harbour, firing on a transport alongside the arsenal, sinking a gunboat and damaging the wharf.

Late in the month, the Ottomans began tunneling around Quinn's Post in the Anzac sector and early in the morning of 29 May, despite Australian counter-mining, detonated a mine and attacked with a battalion from the 14th Regiment.

[147] The 52nd (Lowland) Division also landed at Helles in preparation for the Battle of Gully Ravine, which began on 28 June and achieved a local success, which advanced the British line along the left (Aegean) flank of the battlefield.

[157][158] The Entente planned to land two fresh infantry divisions from IX Corps at Suvla, 5 mi (8.0 km) north of Anzac, followed by an advance on Sari Bair from the north-west.

[162] The landing at Suvla Bay took place on the night of 6 August against light opposition; the British commander, Lieutenant General Frederick Stopford, had limited his early objectives and then failed to forcefully push his demands for an advance inland and little more than the beach was seized.

[168] The New Zealanders held out on Chunuk Bair for two days before being relieved by two New Army battalions from the Wiltshire and Loyal North Lancashire Regiments but an Ottoman counterattack on 10 August, led by Mustafa Kemal, swept them from the heights.

On 23 August, after news of the failure at Scimitar Hill, Hamilton went onto the defensive, as the Bulgarian entry into the war, which would allow the Germans to rearm the Ottoman army, was imminent and left little opportunity for the resumption of offensive operations.

[183] The first French submarine to enter the Sea of Marmara was Turquoise but it was forced to turn back; on 30 October, when returning through the straits, it ran aground beneath a fort and was captured intact.

Troop numbers had been slowly reduced since 7 December and ruses, such as William Scurry's self-firing rifle, which had been rigged to fire by water dripped into a pan attached to the trigger, were used to disguise the Entente departure.

[201] As at Anzac, large amounts of supplies (including 15 British and six French unserviceable artillery pieces which were destroyed), gun carriages and ammunition were left behind; hundreds of horses were slaughtered to deny them to the Ottomans.

[55] The campaign's necessity remains the subject of debate and the recriminations that followed were significant, highlighting the schism that had developed between military strategists who felt the Entente should focus on fighting on the Western Front and those who favoured trying to end the war by attacking Germany's "soft underbelly", its allies in the east.

As it was these operations were a source of anxiety, posing a constant threat to shipping and causing many losses, dislocating Ottoman attempts to reinforce their forces at Gallipoli and shelling troop concentrations and railways.

[231][232] Asquith was partly blamed for Gallipoli and other disasters and was ousted in December 1916, when David Lloyd George proposed a war council under his authority, with the Conservatives in the coalition threatening to resign unless the plan was implemented.

[241] In September 1915 Godley complained that too few of the recovered sick or wounded casualties from Gallipoli were being returned from Egypt, and General John Maxwell replied that "the appetite of the Dardanelles for men has been phenomenal and wicked".

There are a number of memorials and cemeteries on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles, demonstrating the greater emphasis that Turkish historians place on the victory of 18 March over the subsequent fighting on the peninsula.

[268][269] In Egypt, the British Imperial and Dominion troops from the Dardanelles along with fresh divisions from the United Kingdom and those at Salonika, became the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF), commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Murray.