Battle of Marathon

Darius then began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.

The following two hundred years saw the rise of the Classical Greek civilization, which has been enduringly influential in Western society, and so the Battle of Marathon is often seen as a pivotal moment in Mediterranean and European history, and is often celebrated today.

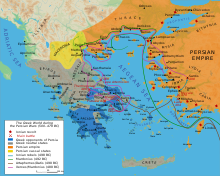

[6] However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability.

[9][10] The Ionian Revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes and the Milesian tyrant Aristagoras.

[13] The involvement of Athens in the Ionian Revolt arose from a complex set of circumstances, beginning with the establishment of the Athenian Democracy in the late 6th century BC.

This tactic succeeded, but the Spartan King, Cleomenes I, returned at the request of Isagoras and so Cleisthenes, the Alcmaeonids and other prominent Athenian families were exiled from Athens.

The result was not actually a democracy or a real civic state, but he enabled the development of a fully democratic government, which would emerge in the next generation as the demos realized its power.

[19] Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but fearing the worst, the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Artaphernes in Sardis, to request aid from the Persian empire.

[27] The pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece and to punish Athens and Eretria.

[30] However, in 490 BC, following the successes of the previous campaign, Darius decided to send a maritime expedition led by Artaphernes (son of the satrap to whom Hippias had fled) and Datis, a Median admiral.

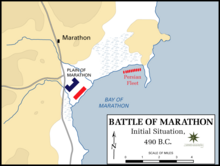

The Persians sailed down the coast of Attica, and landed at the bay of Marathon, about 27 kilometres (17 mi) northeast of Athens, on the advice of the exiled Athenian tyrant Hippias (who had accompanied the expedition).

[35] Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days.

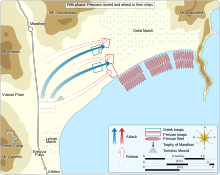

[44] There are many variations of this theory, but perhaps the most prevalent is that the cavalry were completing the time-consuming process of re-embarking on the ships, and were to be sent by sea to attack (undefended) Athens in the rear, whilst the rest of the Persians pinned down the Athenian army at Marathon.

[33] This theory therefore utilises Herodotus' suggestion that after Marathon, the Persian army began to re-embark, intending to sail around Cape Sounion to attack Athens directly.

[61] Among ancient sources, the poet Simonides, another near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000; while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, of which only 100,000 fought in the battle, while the rest were loaded into the fleet that was rounding Cape Sounion;[62] Plutarch and Pausanias both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda dictionary.

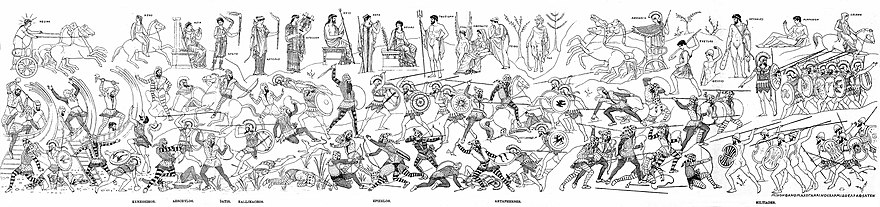

[72] The fleet included various contingents from different parts of the Achaemenid Empire, particularly Ionians and Aeolians, although they are not mentioned as participating directly to the battle and may have remained on the ships:[73] Datis sailed with his army against Eretria first, taking with him Ionians and Aeolians.Regarding the ethnicities involved in the battle, Herodotus specifically mentions the presence of the Persians and the Sakae at the center of the Achaemenid line: They fought a long time at Marathon.

[77] Whatever event eventually triggered the battle, it obviously altered the strategic or tactical balance sufficiently to induce the Athenians to attack the Persians.

If the first theory is correct (see above), then the absence of cavalry removed the main Athenian tactical disadvantage, and the threat of being outflanked made it imperative to attack.

[43] Herodotus implies the Athenians ran the whole distance to the Persian lines, a feat under the weight of hoplite armory generally thought to be physically impossible.

[87] Indeed, based on their previous experience of the Greeks, the Persians might be excused for this; Herodotus tells us that the Athenians at Marathon were "first to endure looking at Median dress and men wearing it, for up until then just hearing the name of the Medes caused the Hellenes to panic".

[45][90] Herodotus recounts the story that Cynaegirus, brother of the playwright Aeschylus, who was also among the fighters, charged into the sea, grabbed one Persian trireme, and started pulling it towards shore.

Lazenby (1993) believes that the ultimate reason for the Greek success was the courage the Greeks displayed: Marathon was won because ordinary, amateur soldiers found the courage to break into a trot when the arrows began to fall, instead of grinding to a halt, and when surprisingly the enemy wings fled, not to take the easy way out and follow them, but to stop and somehow come to the aid of the hard pressured centre.

[96] Connected with this episode, Herodotus recounts a rumour that this manoeuver by the Persians had been planned in conjunction with the Alcmaeonids, the prominent Athenian aristocratic family, and that a "shield-signal" had been given after the battle.

Meanwhile, Darius began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.

"[110] It seems that the Athenian playwright Aeschylus considered his participation at Marathon to be his greatest achievement in life (rather than his plays) since on his gravestone there was the following epigram: Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας· ἀλκὴν δ’ εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι καὶ βαθυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενος

[112] The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon.

[107] As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally.

[121] The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus.

This story first appears in Plutarch's On the Glory of Athens in the 1st century AD, who quotes from Heracleides of Pontus's lost work, giving the runner's name as either Thersipus of Erchius or Eucles.

[135] When the idea of a modern Olympics became a reality at the end of the 19th century, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece.

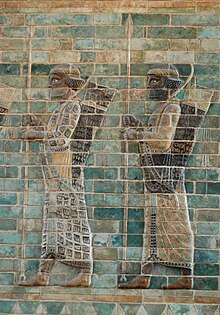

Identical depictions were made on the tombs of other Achaemenid emperors, the best preserved frieze being that of Xerxes I .