Bi-elliptic transfer

In astronautics and aerospace engineering, the bi-elliptic transfer is an orbital maneuver that moves a spacecraft from one orbit to another and may, in certain situations, require less delta-v than a Hohmann transfer maneuver.

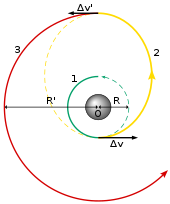

The bi-elliptic transfer consists of two half-elliptic orbits.

At this point a second burn sends the spacecraft into the second elliptical orbit with periapsis at the radius of the final desired orbit, where a third burn is performed, injecting the spacecraft into the desired orbit.

[1] While they require one more engine burn than a Hohmann transfer and generally require a greater travel time, some bi-elliptic transfers require a lower amount of total delta-v than a Hohmann transfer when the ratio of final to initial semi-major axis is 11.94 or greater, depending on the intermediate semi-major axis chosen.

[2] The idea of the bi-elliptical transfer trajectory was first[citation needed] published by Ary Sternfeld in 1934.

[3] The three required changes in velocity can be obtained directly from the vis-viva equation

where In what follows, Starting from the initial circular orbit with radius

(dark blue circle in the figure to the right), a prograde burn (mark 1 in the figure) puts the spacecraft on the first elliptical transfer orbit (aqua half-ellipse).

When the apoapsis of the first transfer ellipse is reached at a distance

from the primary, a second prograde burn (mark 2) raises the periapsis to match the radius of the target circular orbit, putting the spacecraft on a second elliptic trajectory (orange half-ellipse).

Lastly, when the final circular orbit with radius

is reached, a retrograde burn (mark 3) circularizes the trajectory into the final target orbit (red circle).

The final retrograde burn requires a delta-v of magnitude

, then the maneuver reduces to a Hohmann transfer (in that case

required to transfer from a circular orbit of radius

, and is plotted as a function of the ratio of the radii of the final and initial orbits,

; this is done so that the comparison is general (i.e. not dependent of the specific values of

One sees that the Hohmann transfer is always more efficient if the ratio of radii

Between the ratios of 11.94 and 15.58, which transfer is best depends on the apoapsis distance

that results in the bi-elliptic transfer being better for some selected cases.

It even becomes infinite for the bi-parabolic transfer limiting case.

At apoapsis, the spacecraft is travelling at low orbital velocity, and significant changes in periapsis can be achieved for small delta V cost.

Transfers that resemble a bi-elliptic but which incorporate a plane-change maneuver at apoapsis can dramatically save delta-V on missions where the plane needs to be adjusted as well as the altitude, versus making the plane change in low circular orbit on top of a Hohmann transfer.

Likewise, dropping periapsis all the way into the atmosphere of a planetary body for aerobraking is inexpensive in velocity at apoapsis, but permits the use of "free" drag to aid in the final circularization burn to drop apoapsis; though it adds an extra mission stage of periapsis-raising back out of the atmosphere, this may, under some parameters, cost significantly less delta V than simply dropping periapsis in one burn from circular orbit.

The Δv saving could be further improved by increasing the intermediate apogee, at the expense of longer transfer time.

For example, an apogee of 75.8r0 = 507 688 km (1.3 times the distance to the Moon) would result in a 1% Δv saving over a Hohmann transfer, but require a transit time of 17 days.

As an impractical extreme example, an apogee of 1757r0 = 11 770 000 km (30 times the distance to the Moon) would result in a 2% Δv saving over a Hohmann transfer, but the transfer would require 4.5 years (and, in practice, be perturbed by the gravitational effects of other Solar system bodies).

For comparison, the Hohmann transfer requires 15 hours and 34 minutes.

Evidently, the bi-elliptic orbit spends more of its delta-v closer to the planet (in the first burn).

This yields a higher contribution to the specific orbital energy and, due to the Oberth effect, is responsible for the net reduction in required delta-v.