Hill sphere

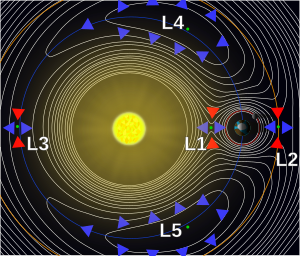

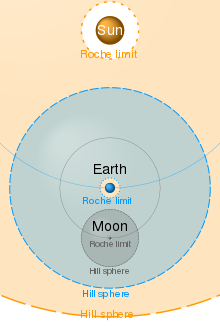

[not verified in body] The gravitational influence of the less massive body is least in that direction, and so it acts as the limiting factor for the size of the Hill sphere;[clarification needed] beyond that distance, a third object in orbit around the Earth would spend at least part of its orbit outside the Hill sphere, and would be progressively perturbed by the tidal forces of the more massive body, the Sun, eventually ending up orbiting the latter.

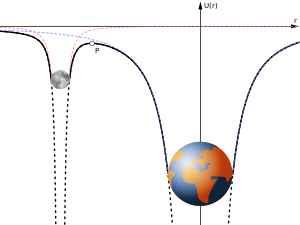

[not verified in body] For two massive bodies with gravitational potentials and any given energy of a third object of negligible mass interacting with them, one can define a zero-velocity surface in space which cannot be passed, the contour of the Jacobi integral.

[not verified in body] When the object's energy is low, the zero-velocity surface completely surrounds the less massive body (of this restricted three-body system), which means the third object cannot escape; at higher energy, there will be one or more gaps or bottlenecks by which the third object may escape the less massive body and go into orbit around the more massive one.

[not verified in body] If the energy is at the border between these two cases, then the third object cannot escape, but the zero-velocity surface confining it touches a larger zero-velocity surface around the less massive body[verification needed] at one of the nearby Lagrange points, forming a cone-like point there.

[5][better source needed] As described by de Pater and Lissauer, all bodies within a system such as the Sun's Solar System "feel the gravitational force of one another", and while the motions of just two gravitationally interacting bodies—constituting a "two-body problem"—are "completely integrable ([meaning]...there exists one independent integral or constraint per degree of freedom)" and thus an exact, analytic solution, the interactions of three (or more) such bodies "cannot be deduced analytically", requiring instead solutions by numerical integration, when possible.

[6]: p.26 For such two- or restricted three-body problems as its simplest examples—e.g., one more massive primary astrophysical body, mass of m1, and a less massive secondary body, mass of m2—the concept of a Hill radius or sphere is of the approximate limit to the secondary mass's "gravitational dominance",[6] a limit defined by "the extent" of its Hill sphere, which is represented mathematically as follows:[6]: p.29 [7] where, in this representation, major axis "a" can be understood as the "instantaneous heliocentric distance" between the two masses (elsewhere abbreviated rp).

of the less massive body, calculated at the pericenter, is approximately:[8][non-primary source needed][better source needed] When eccentricity is negligible (the most favourable case for orbital stability), this expression reduces to the one presented above.

The expression for the Hill radius can be found by equating gravitational and centrifugal forces acting on a test particle (of mass much smaller than

When the test particle is on the line connecting the primary and the secondary body, the force balance requires that where

, can be written as Hence, the relation stated above If the orbit of the secondary about the primary is elliptical, the Hill radius is maximum at the apocenter, where

Therefore, for purposes of stability of test particles (for example, of small satellites), the Hill radius at the pericenter distance needs to be considered.

[citation needed] As stated, the satellite (third mass) should be small enough that its gravity contributes negligibly.

Multi-planet systems of three or more with semi-major-axis differences of less than ten mutual hill radii are always unstable.

For example, an astronaut could not have orbited the 104 ton Space Shuttle at an orbit 300 km above the Earth, because a 104-ton object at that altitude has a Hill sphere of only 120 cm in radius, much smaller than a Space Shuttle.

A sphere of this size and mass would be denser than lead, and indeed, in low Earth orbit, a spherical body must be more dense than lead in order to fit inside its own Hill sphere, or else it will be incapable of supporting an orbit.

Satellites further out in geostationary orbit, however, would only need to be more than 6% of the density of water to fit inside their own Hill sphere.

[citation needed] Within the Solar System, the planet with the largest Hill radius is Neptune, with 116 million km, or 0.775 au; its great distance from the Sun amply compensates for its small mass relative to Jupiter (whose own Hill radius measures 53 million km).

The Hill sphere of 66391 Moshup, a Mercury-crossing asteroid that has a moon (named Squannit), measures 22 km in radius.

[citation needed] The following table and logarithmic plot show the radius of the Hill spheres of some bodies of the Solar System calculated with the first formula stated above (including orbital eccentricity), using values obtained from the JPL DE405 ephemeris and from the NASA Solar System Exploration website.