Binomial theorem

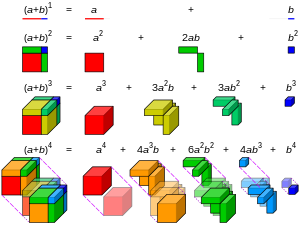

According to the theorem, the expansion of any nonnegative integer power n of the binomial x + y is a sum of the form

A simple variant of the binomial formula is obtained by substituting 1 for y, so that it involves only a single variable.

Substituting this into the definition of the derivative via a difference quotient and taking limits means that the higher order terms,

can be interpreted as the number of ways to choose k elements from an n-element set (a combination).

Therefore, after combining like terms, the coefficient of xn−2y2 will be equal to the number of ways to choose exactly 2 elements from an n-element set.

Around 1665, Isaac Newton generalized the binomial theorem to allow real exponents other than nonnegative integers.

In order to do this, one needs to give meaning to binomial coefficients with an arbitrary upper index, which cannot be done using the usual formula with factorials.

The generalized binomial theorem is valid also for elements x and y of a Banach algebra as long as xy = yx, and x is invertible, and ‖y/x‖ < 1.

A version of the binomial theorem is valid for the following Pochhammer symbol-like family of polynomials: for a given real constant c, define

where the summation is taken over all sequences of nonnegative integer indices k1 through km such that the sum of all ki is n. (For each term in the expansion, the exponents must add up to n).

counts the number of different ways to partition an n-element set into disjoint subsets of sizes k1, ..., km.

The general Leibniz rule gives the nth derivative of a product of two functions in a form similar to that of the binomial theorem:[6]

If one sets f(x) = eax and g(x) = ebx, cancelling the common factor of e(a + b)x from each term gives the ordinary binomial theorem.

[8] Indian mathematician Aryabhata's method for finding cube roots, from around 510 AD, suggests that he knew the binomial formula for exponent

[8] Binomial coefficients, as combinatorial quantities expressing the number of ways of selecting k objects out of n without replacement (combinations), were of interest to ancient Indian mathematicians.

The Jain Bhagavati Sutra (c. 300 BC) describes the number of combinations of philosophical categories, senses, or other things, with correct results up through

(probably obtained by listing all possibilities and counting them)[9] and a suggestion that higher combinations could likewise be found.

[10] The Chandaḥśāstra by the Indian lyricist Piṅgala (3rd or 2nd century BC) somewhat crypically describes a method of arranging two types of syllables to form metres of various lengths and counting them; as interpreted and elaborated by Piṅgala's 10th-century commentator Halāyudha his "method of pyramidal expansion" (meru-prastāra) for counting metres is equivalent to Pascal's triangle.

[12] By the 9th century at latest Indian mathematicians learned to express this as a product of fractions

[14][15][16] An explicit statement of the binomial theorem appears in al-Samawʾal's al-Bāhir (12th century), there credited to al-Karajī.

He then provided al-Karajī's table of binomial coefficients (Pascal's triangle turned on its side) up to

[14][18] The Persian poet and mathematician Omar Khayyam was probably familiar with the formula to higher orders, although many of his mathematical works are lost.

[8] The binomial expansions of small degrees were known in the 13th century mathematical works of Yang Hui[19] and also Chu Shih-Chieh.

[8] Yang Hui attributes the method to a much earlier 11th century text of Jia Xian, although those writings are now also lost.

[21] In 1544, Michael Stifel introduced the term "binomial coefficient" and showed how to use them to express

[22] Other 16th century mathematicians including Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia and Simon Stevin also knew of it.

[24] Isaac Newton is generally credited with discovering the generalized binomial theorem, valid for any real exponent, in 1665, inspired by the work of John Wallis's Arithmetic Infinitorum and his method of interpolation.

[22][25][8][26][24] A logarithmic version of the theorem for fractional exponents was discovered independently by James Gregory who wrote down his formula in 1670.

Applying the binomial theorem to this expression yields the usual infinite series for e. In particular:

[27] The binomial theorem is valid more generally for two elements x and y in a ring, or even a semiring, provided that xy = yx.