Biochemistry

[5] Much of biochemistry deals with the structures, functions, and interactions of biological macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids.

In recent decades, biochemical principles and methods have been combined with problem-solving approaches from engineering to manipulate living systems in order to produce useful tools for research, industrial processes, and diagnosis and control of disease—the discipline of biotechnology.

[17] The term "biochemistry" was first used when Vinzenz Kletzinsky (1826–1882) had his "Compendium der Biochemie" printed in Vienna in 1858; it derived from a combination of biology and chemistry.

[25] In 1828, Friedrich Wöhler published a paper on his serendipitous urea synthesis from potassium cyanate and ammonium sulfate; some regarded that as a direct overthrow of vitalism and the establishment of organic chemistry.

[28] Since then, biochemistry has advanced, especially since the mid-20th century, with the development of new techniques such as chromatography, X-ray diffraction, dual polarisation interferometry, NMR spectroscopy, radioisotopic labeling, electron microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations.

[citation needed] Another significant historic event in biochemistry is the discovery of the gene, and its role in the transfer of information in the cell.

In the 1950s, James D. Watson, Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins were instrumental in solving DNA structure and suggesting its relationship with the genetic transfer of information.

[29] In 1958, George Beadle and Edward Tatum received the Nobel Prize for work in fungi showing that one gene produces one enzyme.

[30] In 1988, Colin Pitchfork was the first person convicted of murder with DNA evidence, which led to the growth of forensic science.

Fire and Craig C. Mello received the 2006 Nobel Prize for discovering the role of RNA interference (RNAi) in the silencing of gene expression.

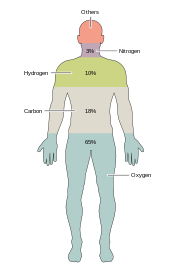

Most rare elements on Earth are not needed by life (exceptions being selenium and iodine),[33] while a few common ones (aluminum and titanium) are not used.

[citation needed] The simplest type of carbohydrate is a monosaccharide, which among other properties contains carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, mostly in a ratio of 1:2:1 (generalized formula CnH2nOn, where n is at least 3).

Glucose (C6H12O6) is one of the most important carbohydrates; others include fructose (C6H12O6), the sugar commonly associated with the sweet taste of fruits,[36][a] and deoxyribose (C5H10O4), a component of DNA.

These forms are called furanoses and pyranoses, respectively—by analogy with furan and pyran, the simplest compounds with the same carbon-oxygen ring (although they lack the carbon-carbon double bonds of these two molecules).

[citation needed] Two monosaccharides can be joined by a glycosidic or ester bond into a disaccharide through a dehydration reaction during which a molecule of water is released.

Cellulose is an important structural component of plant's cell walls and glycogen is used as a form of energy storage in animals.

A reducing end of a carbohydrate is a carbon atom that can be in equilibrium with the open-chain aldehyde (aldose) or keto form (ketose).

If the joining of monomers takes place at such a carbon atom, the free hydroxy group of the pyranose or furanose form is exchanged with an OH-side-chain of another sugar, yielding a full acetal.

Lipids comprise a diverse range of molecules and to some extent is a catchall for relatively water-insoluble or nonpolar compounds of biological origin, including waxes, fatty acids, fatty-acid derived phospholipids, sphingolipids, glycolipids, and terpenoids (e.g., retinoids and steroids).

In general, the bulk of their structure is nonpolar or hydrophobic ("water-fearing"), meaning that it does not interact well with polar solvents like water.

Lipid-containing foods undergo digestion within the body and are broken into fatty acids and glycerol, the final degradation products of fats and lipids.

Lipids, especially phospholipids, are also used in various pharmaceutical products, either as co-solubilizers (e.g. in parenteral infusions) or else as drug carrier components (e.g. in a liposome or transfersome).

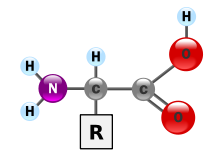

It is this "R" group that makes each amino acid different, and the properties of the side chains greatly influence the overall three-dimensional conformation of a protein.

[44] The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which uses antibodies, is one of the most sensitive tests modern medicine uses to detect various biomolecules.

Mammals do possess the enzymes to synthesize alanine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine, the nonessential amino acids.

While they can synthesize arginine and histidine, they cannot produce it in sufficient amounts for young, growing animals, and so these are often considered essential amino acids.

[2] The monomers are called nucleotides, and each consists of three components: a nitrogenous heterocyclic base (either a purine or a pyrimidine), a pentose sugar, and a phosphate group.

The phosphate group and the sugar of each nucleotide bond with each other to form the backbone of the nucleic acid, while the sequence of nitrogenous bases stores the information.

In vertebrates, vigorously contracting skeletal muscles (during weightlifting or sprinting, for example) do not receive enough oxygen to meet the energy demand, and so they shift to anaerobic metabolism, converting glucose to lactate.

The pathway is a crucial reversal of glycolysis from pyruvate to glucose and can use many sources like amino acids, glycerol and Krebs Cycle.