Biomolecular condensate

[2] Amorphous substances such as starch and cellulose were proposed to consist of building blocks, packed in a loosely crystalline array to form what he later termed "micelles".

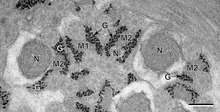

[3][4] Around the same time, Thomas Harrison Montgomery Jr. described the morphology of the nucleolus, an organelle within the nucleus, which has subsequently been shown to form through intracellular phase separation.

[27] Unfortunately, de Gennes wrote in Nature that polymers should be distinguished from other types of colloids, even though they can display similar clustering and phase separation behaviour,[28] a stance that has been reflected in the reduced usage of the term colloid to describe the higher-order association behaviour of biopolymers in modern cell biology and molecular self-assembly.

Advances in confocal microscopy at the end of the 20th century identified proteins, RNA or carbohydrates localising to many non-membrane bound cellular compartments within the cytoplasm or nucleus which were variously referred to as 'puncta/dots',[29][30][31][32] 'signalosomes',[33][34] 'granules',[35] 'bodies', 'assemblies',[32] 'paraspeckles', 'purinosomes',[36] 'inclusions', 'aggregates' or 'factories'.

During this time period (1995-2008) the concept of phase separation was re-borrowed from colloidal chemistry & polymer physics and proposed to underlie both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartmentalization.

The formation of these structures involves phase separation to from colloidal micelles or liquid crystal bilayers, but they are not classified as biomolecular condensates, as this term is reserved for non-membrane bound organelles.

[68] However, unequivocally demonstrating that a cellular body forms through liquid–liquid phase separation is challenging,[69][47][70][71] because different material states (liquid vs. gel vs. solid) are not always easy to distinguish in living cells.

Historically, many cellular non-membrane bound compartments identified microscopically fall under the broad umbrella of biomolecular condensates.

Growing evidence suggests that anomalies in biomolecular condensates formation can lead to a number of human pathologies[79] such as cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

[89] They are speculated to facilitate the formation of phase-separated inclusions, aiding in the storage and transport of specific metabolites[90] such as anthocyanins,[91] dhurrin,[92] and vanillin.

Engineered synthetic condensates allow for probing cellular organization, and enable the creation of novel functionalized biological materials, which have the potential to serve as drug delivery platforms and therapeutic agents.

[98] Other tools outside of tuning the sticker-spacer framework can be used to give new functionality and to allow for high temporal and spatial control over synthetic condensates.

Several different systems have been developed which allow for control of condensate formation and dissolution which rely on chimeric protein expression, and light or small molecule activation.

In this case, light-activation removes the dimerizer cage, allowing it to recruit IDRs to multivalent cores, which then triggers phase separation.

When oligomerization is trigger by light activation, phase separation is preferentially induced on the specific genomic region which is recognized by fusion protein.

[103] These binding sites can be modified to be sensitive to light activation or small molecule addition, thus giving temporal control over the recruitment of a specific protein of interest.

By recruiting specific proteins to condensates, reactants can be concentrated to increase reaction rates or sequestered to inhibit reactivity.

[103] A number of experimental and computational methods have been developed to examine the physico-chemical properties and underlying molecular interactions of biomolecular condensates.

[106] Molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations have been extensively used to gain insights into the formation and the material properties of biomolecular condensates.

Compared to more detailed molecular descriptions, residue-level models provide high computational efficiency, which enables simulations to cover the long length and time scales required to study phase separation.

Their common features are (i) the absence of an explicit representation of solvent molecules and salt ions, (ii) a mean-field description of the electrostatic interactions between charged residues (see Debye–Hückel theory), and (iii) a set of "stickiness" parameters which quantify the strength of the attraction between pairs of amino acids.

In the development of most residue-level models, the stickiness parameters have been derived from hydrophobicity scales[111] or from a bioinformatic analysis of crystal structures of folded proteins.

[112][113] Further refinement of the parameters has been achieved through iterative procedures which maximize the agreement between model predictions and a set of experiments,[114][115][116][117][118][119] or by leveraging data obtained from all-atom molecular dynamics simulations.

[113] Residue-level models of intrinsically disordered proteins have been validated by direct comparison with experimental data, and their predictions have been shown to be accurate across diverse amino acid sequences.