Black Moshannon State Park

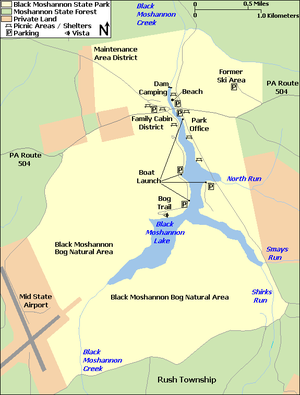

The park is just west of the Allegheny Front, 9 miles (14 km) east of Philipsburg on Pennsylvania Route 504, and is largely surrounded by Moshannon State Forest.

A bog in the park provides a habitat for diverse wildlife not common in other areas of the state, such as carnivorous plants, orchids, and species normally found farther north.

Black Moshannon State Park rose from the ashes of a depleted forest which had been largely destroyed by wildfire in the years following the lumber era.

Archeological evidence found in the state from this time includes a range of pottery types and styles, burial mounds, pipes, bows and arrow, and ornaments.

[8] Black Moshannon Creek is in the West Branch Susquehanna River drainage basin, whose earliest recorded Native American inhabitants were the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks.

[9] To fill the void left by the demise of the Susquehannocks, the Iroquois encouraged displaced tribes from the east to settle in the West Branch watershed, including the Lenape (or Delaware).

[9] The Seneca, members of the Iroquois Confederacy, became inhabitants in the area of Black Moshannon Lake, which was a series of beaver ponds at the time.

[10] The park's 1-mile (1.6 km) Indian Trail for hiking and cross-country skiing recalls such native paths as it runs through an open forest of oak and pine trees, with occasional clearings and a grove of hawthorns.

[9] On November 5, 1768, the British acquired the "New Purchase" from the Iroquois in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, including what is now Black Moshannon State Park.

[13][14] The name "Black Moshannon" refers to the dark color of the water, a result of plant tannins from the local vegetation and bog.

[4] Prior to the arrival of William Penn and his Quaker colonists in 1682, an estimated 90 percent of what is now Pennsylvania was covered with old-growth forest: over 31,000 square miles (80,000 km2) of white pine, eastern hemlock, and a mix of hardwoods.

[15] The forests near the three original counties, Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester, were the first to be harvested, as the early settlers used the readily available timber to build homes, barns, and ships, and cleared the land for agriculture.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought thousands of acres of deforested and burned land, then began the project of reforestation.

By the 1930s, the land that became Black Moshannon State Park was already a place for picnics and camping, on the aptly named "Tent Hill", and people swam and fished in the old mill pond.

They cut roads through the growing forest to aid in fighting the wildfires that sprang up, and planted many acres of red pines as part of the reforestation effort.

[22] Most of the CCC-built park facilities are still in use today, including log cabins, picnic pavilions, a food concession stand, and miles of trails.

[18] Four open pit latrines with wane edge siding and hipped roofs were also contributing structures to the Beach and Day Use district.

In 1941, Governor Arthur James announced plans to expand the park to 1,000 acres (400 ha) by annexing surrounding state forest land.

[29] While the airport was designated a Keystone Opportunity Zone to encourage business growth,[30] there are limitations in state law that prohibit any further development on park or forest lands.

It begins at the beach parking lot, climbs Rattlesnake Mountain, and crosses Pennsylvania Route 504 near a historical marker for the Philadelphia–Erie Turnpike.

[40] In 2019, the state paid $299,000 to the Philipsburg Rod and Gun Club, which had leased 23 acres (9.3 ha) near the Organized Group Tenting area in the park for over 60 years.

[44] The park itself is part of a much larger Important Bird Area, which includes most of the surrounding state forest, airport, and private properties.

[44] White-tailed deer, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, opossum, raccoon, hawks, chipmunks, porcupine, woodpeckers, and flying, red, and eastern gray squirrels are all fairly common in the park.

[40][44] The conifer and mixed-forests of the park and its surroundings provide habitats for northern saw-whet owl, blue-headed vireo, hermit thrush, dark-eyed junco, and magnolia, pine, yellow-rumped, Blackburnian, and black-throated green warblers.

Today the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) Sleepy Hollow Trail for hiking, biking, and cross-country skiing loops through the new growth in the area, which provides an ideal habitat for populations of white-tailed deer and wild turkey.

Several factors contribute to the high total of bird species observed: there is a large area of forest in the IBA, as well as great habitat diversity.

The Canada warbler and northern waterthrush nest in the bogs, as do the alder flycatcher, common yellowthroat, swamp sparrow, red-winged blackbird, and gray catbird.

The olive-sided flycatcher, which is designated as locally extinct in Pennsylvania, has been seen during the breeding season at Black Moshannon State Natural Area.

Canoes, sailboats, and electric motor boats are all permitted on Black Moshannon Lake, provided they are properly registered with the state.

Black Moshannon Lake's waters are warmer than those of the creek, and so hold many different species of fish, including largemouth bass, yellow perch, chain pickerel, bullhead catfish, northern pike, bluegill, and crappie.