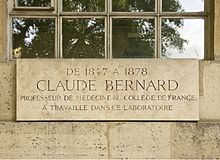

Commemorative plaque

The Benin Empire, which flourished in present-day Nigeria between the thirteenth and nineteenth centuries, had an exceedingly rich sculptural tradition.

One of the kingdom's chief sites of cultural production was the elaborate ceremonial court of the Oba (divine king) at the palace in Benin.

Surviving in great numbers, they were manufactured from sheet brass or latten, very occasionally coloured with enamels, and tend to depict highly conventional figures with brief inscriptions.

In addition to geographically defined regions, individual organizations, such as E Clampus Vitus or the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, can choose to maintain a national set of historical markers that fit a certain theme.

People and places recognised by the first batch of plaques to be erected include Bessie Robinson of Canowindra and Duke Kahanamoku and Camden Red Cross.

[19] In November 2023 it was announced that a further 14 people, places and events would be commemorated in the second round of blue plaques sponsored by the Government of New South Wales, chosen from 117 public nominations: Kathleen Butler, godmother of Sydney Harbour Bridge; Emma Jane Callaghan, an Aboriginal midwife and activist; Susan Katherina Schardt; journalist Dorothy Drain; writer Charmian Clift; Beryl Mary McLaughlin, one of the first three women to graduate in architecture from the University of Sydney; Grace Emily Munro, Sir William Dobell, Ioannis (Jack) and Antonios (Tony) Notaras; Syms Covington; Ken Thomas of Thomas Nationwide Transport, Bondi Surf Bathers' Life Saving Club and the first release of myxomatosis.

[20][21] To mark the 60th anniversary of the 1965 Freedom Ride in which a group of students toured country towns to highlight discrimination against Aboriginal Australians, in February 2025 the Government of New South Wales unveiled a blue plaque commemorating in Walgett, the first of several to be installed in key locations along the route.

[22][23] Historical markers (Filipino: panandang pangkasaysayan; Spanish: marcador histórico) are cast-iron plaques installed all over the Philippines that commemorate people, places, personalities, structures, and events.

This practice started in 1933, with NHCP's predecessor, the Philippine Historical Research and Markers Committee, which initially only marked antiquities in Manila.

An example is the blue plaque scheme run by English Heritage in London, although these were originally erected in a variety of shapes and colors.

[28][29] The Dead Comics' Society installs blue plaques to commemorate the former residences of well-known comedians, including those of Sid James and John Le Mesurier.

A range of other commemorative plaque schemes, which are typically run by local councils and charitable bodies, exists throughout the United Kingdom.

Other schemes are run by civic societies, district or town councils, or local history groups, and often operate with different criteria.

[35] Other examples of mostly locally generated historical markers in the United States include: See also: Plaques or, more often, plaquettes, are also given as awards instead of trophies or ribbons.