Bluntnose stingray

Typically growing to 78 cm (31 in) across, the bluntnose stingray is characterized by a rhomboid pectoral fin disc with broadly rounded outer corners and an obtuse-angled snout.

More active at night than during the day when it is usually buried in sediment, the bluntnose stingray is a predator of small benthic invertebrates and bony fishes.

This species is aplacental viviparous, in which the unborn young are nourished initially by yolk, and later histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by their mother.

[1] French naturalist Charles Alexandre Lesueur originally described the bluntnose stingray from specimens collected in Little Egg Harbor off the U.S. State of New Jersey.

In 1841, German biologists Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle erroneously gave the specific epithet as sayi in their Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen, which thereafter became the typical spelling used in literature.

Along the U.S. East Coast, schools of bluntnose stingrays migrate long distances northward into bays and estuaries to spend the summer, and move back to southern offshore waters for winter.

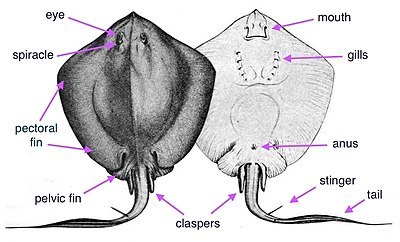

[9][10] The bluntnose stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc about a sixth wider than long, with broadly rounded outer corners.

Small thorns or tubercles are found in a midline row from behind the eyes to the base of the tail spine, increasing in number with age.

The dorsal coloration is grayish, reddish, or greenish brown; some individuals also possess bluish spots, are darker towards the sides and rear, or have a thin white disc margin.

[15] This species preys upon small invertebrates, including crustaceans, annelid worms, and bivalve and gastropod molluscs, and bony fishes.

[7] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Acanthobothrium brevissime and Kotorella pronosoma,[16][17] the monogenean Listrocephalos corona,[18] and the trematodes Monocotyle pricei and Multicalyx cristata.

[7] Abundant and widespread, the bluntnose stingray is caught incidentally by commercial trawl and gillnet fisheries operating in nearshore U.S. waters; these activities are not a threat to its population, as most captured rays are released alive.

The impact of fishing in the southern parts of its range is uncertain, but is unlikely to significantly affect the species as a whole as these activities occur outside its centers of distribution.

External anatomy of a male bluntnose stingray