Boltzmann equation

[2] The classic example of such a system is a fluid with temperature gradients in space causing heat to flow from hotter regions to colder ones, by the random but biased transport of the particles making up that fluid.

In the modern literature the term Boltzmann equation is often used in a more general sense, referring to any kinetic equation that describes the change of a macroscopic quantity in a thermodynamic system, such as energy, charge or particle number.

The equation arises not by analyzing the individual positions and momenta of each particle in the fluid but rather by considering a probability distribution for the position and momentum of a typical particle—that is, the probability that the particle occupies a given very small region of space (mathematically the volume element

The Boltzmann equation can be used to determine how physical quantities change, such as heat energy and momentum, when a fluid is in transport.

The problem of existence and uniqueness of solutions is still not fully resolved, but some recent results are quite promising.

[3][4] The set of all possible positions r and momenta p is called the phase space of the system; in other words a set of three coordinates for each position coordinate x, y, z, and three more for each momentum component px, py, pz.

While f is associated with a number of particles, the phase space is for one-particle (not all of them, which is usually the case with deterministic many-body systems), since only one r and p is in question.

If a force F instantly acts on each particle, then at time t + Δt their position will be

is a shorthand for the momentum analogue of ∇, and êx, êy, êz are Cartesian unit vectors.

Under this assumption the collision term can be written as a momentum-space integral over the product of one-particle distribution functions:[2]

[7] The assumption in the BGK approximation is that the effect of molecular collisions is to force a non-equilibrium distribution function at a point in physical space back to a Maxwellian equilibrium distribution function and that the rate at which this occurs is proportional to the molecular collision frequency.

is the local Maxwellian distribution function given the gas temperature at this point in space.

The sum of integrals describes the entry and exit of particles of species i in or out of the phase-space element.

The Boltzmann equation can be used to derive the fluid dynamic conservation laws for mass, charge, momentum, and energy.

This has several applications in physical cosmology,[9] including the formation of the light elements in Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the production of dark matter and baryogenesis.

It is not a priori clear that the state of a quantum system can be characterized by a classical phase space density f. However, for a wide class of applications a well-defined generalization of f exists which is the solution of an effective Boltzmann equation that can be derived from first principles of quantum field theory.

A galaxy, under certain assumptions, may be approximated as a continuous fluid; its mass distribution is then represented by f; in galaxies, physical collisions between the stars are very rare, and the effect of gravitational collisions can be neglected for times far longer than the age of the universe.

where Γαβγ is the Christoffel symbol of the second kind (this assumes there are no external forces, so that particles move along geodesics in the absence of collisions), with the important subtlety that the density is a function in mixed contravariant-covariant (xi, pi) phase space as opposed to fully contravariant (xi, pi) phase space.

[12][13] In physical cosmology the fully covariant approach has been used to study the cosmic microwave background radiation.

[14] More generically the study of processes in the early universe often attempt to take into account the effects of quantum mechanics and general relativity.

[9] In the very dense medium formed by the primordial plasma after the Big Bang, particles are continuously created and annihilated.

In such an environment quantum coherence and the spatial extension of the wavefunction can affect the dynamics, making it questionable whether the classical phase space distribution f that appears in the Boltzmann equation is suitable to describe the system.

In many cases it is, however, possible to derive an effective Boltzmann equation for a generalized distribution function from first principles of quantum field theory.

[10] This includes the formation of the light elements in Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the production of dark matter and baryogenesis.

Exact solutions to the Boltzmann equations have been proven to exist in some cases;[15] this analytical approach provides insight, but is not generally usable in practical problems.

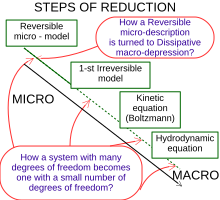

The problem of developing mathematically the limiting processes, which lead from the atomistic view (represented by Boltzmann's equation) to the laws of motion of continua, is an important part of Hilbert's sixth problem.

[22] The collision term is modified in Enskog equations such that particles have a finite size, for example they can be modelled as spheres having a fixed radius.

If there are internal degrees of freedom, the Boltzmann equation has to be generalized and might possess inelastic collisions.

[24][25] Since cells are composite particles that carry internal degrees of freedom, the corresponding generalized Boltzmann equations must have inelastic collision integrals.

Such equations can describe invasions of cancer cells in tissue, morphogenesis, and chemotaxis-related effects.