Buchwald–Hartwig amination

[1] Although Pd-catalyzed C–N couplings were reported as early as 1983, Stephen L. Buchwald and John F. Hartwig have been credited, whose publications between 1994 and the late 2000s established the scope of the transformation.

The reaction's synthetic utility stems primarily from the shortcomings of typical methods (nucleophilic substitution, reductive amination, etc.)

In February 1994, Hartwig reported a systematic study of the palladium compounds involved in the original Migita paper, concluding that the d10 complex Pd[P(o-Tolyl)3]2 was the active catalyst.

First, transamination of Bu3SnNEt2 followed by argon purge to remove the volatile diethylamine allowed extension of the methodology to a variety of secondary amines (both cyclic and acyclic) and primary anilines.

Though these improved conditions proceeded at a faster rate, the substrate scope was limited almost entirely to secondary amines due to competitive hydrodehalogenation of the bromoarenes.

The following years saw development of more sophisticated phosphine ligands that allowed extension to a larger variety of amines and aryl groups.

Aryl iodides, chlorides, and triflates eventually became suitable substrates, and reactions run with weaker bases at room temperature were developed.

The stability of this dimer decreases in the order of X = I > Br > Cl, and is thought to be responsible for the slow reaction of aryl iodides with the first-generation catalyst system.

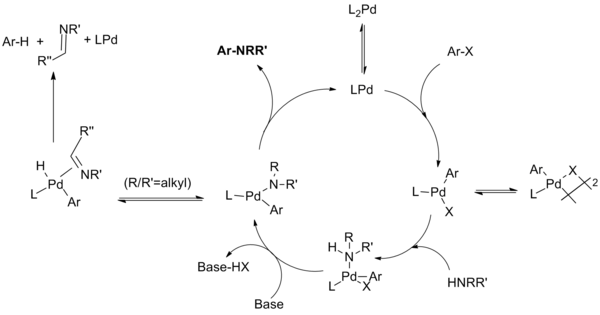

For chelating ligands, the monophosphine palladium species is not formed; oxidative addition, amide formation and reductive elimination occur from L2Pd complexes.

The Hartwig group found that "reductive elimination can occur from either a four-coordinate bisphosphine or three-coordinate monophosphine arylpalladium amido complex.

Various ligand systems have been developed, each with varying capabilities and limitations, and the choice of conditions requires consideration of the steric and electronic properties of both partners.

[7][8] Aryl iodides were found to be suitable substrates for the intramolecular variant of this reaction,[8] and importantly, could be coupled intermolecularly only if dioxane was used in place of toluene as a solvent, albeit with modest yields.

In fact, α-chiral amines were found not to racemize when chelating ligands were employed, in contrast to the first-generation catalyst system.

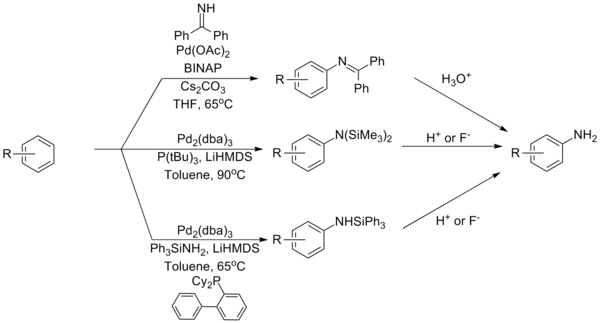

[28] Bulky tri- and di-alkyl phosphine ligands have been shown to be remarkably active catalysts, allowing the coupling of a wide range of amines (primary, secondary, electron withdrawn, heterocyclic, etc.)

[35][36] Ammonia remains one of the most challenging coupling partners for Buchwald–Hartwig amination reactions, a problem attributed to its tight binding with palladium complexes.