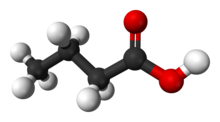

Butyric acid

Butyric acid was first observed in an impure form in 1814 by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul.

However, Chevreul did not publish his early research on butyric acid; instead, he deposited his findings in manuscript form with the secretary of the Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

Henri Braconnot, a French chemist, was also researching the composition of butter and was publishing his findings and this led to disputes about priority.

[16][17] Butyric acid is present as its octyl ester in parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)[18] and in the seed of the ginkgo tree.

[19] In industry, butyric acid is produced by hydroformylation from propene and syngas, forming butyraldehyde, which is oxidised to the final product.

Examples of butyrate-producing species of bacteria: The pathway starts with the glycolytic cleavage of glucose to two molecules of pyruvate, as happens in most organisms.

This intermediate then takes two possible pathways: For commercial purposes Clostridium species are used preferably for butyric acid or butanol production.

[23] The production of SCFA from fibers in ruminant animals such as cattle is responsible for the butyrate content of milk and butter.

Sources of fructans include wheat (although some wheat strains such as spelt contain lower amounts),[26] rye, barley, onion, garlic, Jerusalem and globe artichoke, asparagus, beetroot, chicory, dandelion leaves, leek, radicchio, the white part of spring onion, broccoli, brussels sprouts, cabbage, fennel, and prebiotics, such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS), oligofructose, and inulin.

[32] Many of the commercially available flavors used in carp (Cyprinus carpio) baits use butyric acid as their ester base.

[33] The substance has been used as a stink bomb by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society to disrupt Japanese whaling crews.

[34] Butyric acid (pKa 4.82) is fully ionized at physiological pH, so its anion is the material that is mainly relevant in biological systems.

[39] In general, it is thought that transcription factors will be unable to access regions where histones are tightly associated with DNA (i.e., non-acetylated, e.g., heterochromatin).

[37] Although the role and importance of butyrate in the gut is not fully understood, many researchers argue that a depletion of butyrate-producing bacteria in patients with several vasculitic conditions is essential to the pathogenesis of these disorders.

Butyrate is an essential microbial metabolite with a vital role as a modulator of proper immune function in the host.

[49] Butyrate is also reduced in a diet low in dietary fiber, which can induce inflammation and have other adverse affects insofar as these short-chain fatty acids activate PPAR-γ.

The low-levels of butyrate in human subjects could favor reduced regulatory T cell-mediated control, thus promoting a powerful immuno-pathological T-cell response.

Conversely, a high-fiber diet results in higher butyric acid concentration and inhibition of C. difficile growth.

[53] In a 2013 research study conducted by Furusawa et al., microbe-derived butyrate was found to be essential in inducing the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells in mice.

[56] More recently, it has been shown that butyrate plays an essential and direct role in modulating gene expression of cytotoxic T-cells.

[58] In the gut microbiomes found in the class Mammalia, omnivores and herbivores have butyrate-producing bacterial communities dominated by the butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase pathway, whereas carnivores have butyrate-producing bacterial communities dominated by the butyrate kinase pathway.

[59] The odor of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal.

Butyrate's effects on the immune system are mediated through the inhibition of class I histone deacetylases and activation of its G-protein coupled receptor targets: HCA2 (GPR109A), FFAR2 (GPR43), and FFAR3 (GPR41).

[38][60] Among the short-chain fatty acids, butyrate is the most potent promoter of intestinal regulatory T cells in vitro and the only one among the group that is an HCA2 ligand.

[64][65][66] Butyrate binding at FFAR3 induces neuropeptide Y release and promotes the functional homeostasis of colonic mucosa and the enteric immune system.

[68] Butyrate possesses both preventive and therapeutic potential to counteract inflammation-mediated ulcerative colitis (UC) and colorectal cancer.

It is thus suggested that butyrate enhances apoptosis of T cells in the colonic tissue and thereby eliminates the source of inflammation (IFN-γ production).

These short-chain fatty acids benefit the colonocytes by increasing energy production, and may protect against colon cancer by inhibiting cell proliferation.

Fecal microbiota transplants (to restore BPB and symbiosis in the gut) could be effective by replenishing butyrate levels.

A less-invasive treatment option is the administration of butyrate—as oral supplements or enemas—which has been shown to be very effective in terminating symptoms of inflammation with minimal-to-no side-effects.