Carbon–fluorine bond

The bond also strengthens and shortens as more fluorines are added to the same carbon on a chemical compound.

For this reason, fluoroalkanes like tetrafluoromethane (carbon tetrafluoride) are some of the most unreactive organic compounds.

For example, the BDEs of the C–X bond within a CH3–X molecule is 115, 104.9, 83.7, 72.1, and 57.6 kcal/mol for X = fluorine, hydrogen, chlorine, bromine, and iodine, respectively.

[5][6][7][8] With increasing number of fluorine atoms on the same (geminal) carbon the other bonds become stronger and shorter.

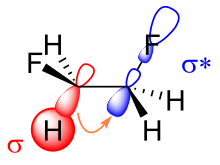

The resulting reduced orbital overlap can be partially compensated when a gauche conformation is assumed, forming a bent bond.

[14] Organofluorine compounds can also be characterized using NMR spectroscopy, using carbon-13, fluorine-19 (the only natural fluorine isotope), or hydrogen-1 (if present).

The chemical shifts in 19F NMR appear over a very wide range, depending on the degree of substitution and functional group.

[15] Breaking C–F bonds is of interest as a way to decompose and destroy organofluorine "forever chemicals" such as PFOA and perfluorinated compounds (PFCs).

Candidate methods include catalysts, such as platinum atoms;[16] photocatalysts; UV, iodide, and sulfite,[17] radicals; etc.

An illustrative metal-mediated C-F activation reaction is the defluorination of fluorohexane by a zirconocene dihydride: