Canons of page construction

The notion of canons, or laws of form, of book page construction was popularized by Jan Tschichold in the mid to late twentieth century, based on the work of J. A.

[1] Tschichold wrote: "Though largely forgotten today, methods and rules upon which it is impossible to improve have been developed for centuries.

[4] The Van de Graaf canon is a historical reconstruction of a method that may have been used in book design to divide a page in pleasing proportions.

Tschichold writes: "For purposes of better comparison I have based his figure on a page proportion of 2:3, which Van de Graaf does not use.

[11] Tschichold's "golden canon of page construction"[10] is based on simple integer ratios, equivalent to Rosarivo's "typographical divine proportion".

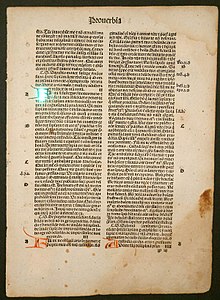

[12] Raúl Rosarivo analyzed Renaissance-era books with the help of a drafting compass and a ruler, and concluded in his Divina proporción tipográfica ("Typographical Divine Proportion", first published in 1947) that Gutenberg, Peter Schöffer, Nicolaus Jenson and others had applied the golden canon of page construction in their works.

[15] Ros Vicente points out that Rosarivo "demonstrates that Gutenberg had a module different from the well-known one of Luca Pacioli" (the golden ratio).

Hendel writes that since Gutenberg's time, books have been most often printed in an upright position, that conform loosely, if not precisely, to the golden ratio.

"[21] John Man's quoted Gutenberg page sizes are in a proportion not very close to the golden ratio,[22] but Rosarivo's or van de Graaf's construction is applied by Tschichold to make a pleasing type area on pages of arbitrary proportions, even such accidental ones.

Richard Hendel, associate director of the University of North Carolina Press, describes book design as a craft with its own traditions and a relatively small body of accepted rules.

Christopher Burke, in his book on German typographer Paul Renner, creator of the Futura typeface, described his views about page proportions: Renner still championed the traditional proportions of margins, with the largest at the bottom of a page, 'because we hold the book by the lower margin when we take it in the hand and read it'.