Carboniferous rainforest collapse

This event may have fragmented the forests into isolated refugia or ecological "islands", which in turn encouraged dwarfism and, shortly after, extinction of many plant and animal species.

The rise of rainforests in the Carboniferous greatly altered the landscapes by eroding low-energy, organic-rich anastomosing (braided) river systems with multiple channels and stable alluvial islands.

[4] This is confirmed by a 2011 study showing that the presence of meandering and anabranching streams, occurrences of large woody debris, and records of log jams decrease significantly at the Moscovian-Kasimovian boundary.

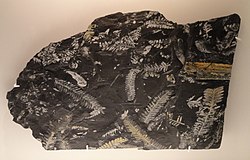

This study found a Late Pennsylvanian extinction pulse that reflects drying climates and the transition of lycopod to tree fern-dominated land floras.

This theory was originally developed for oceanic islands, but it can be applied equally well to any other ecosystem that is fragmented, only existing in small patches and surrounded by another unsuitable habitat.

[8] By the Asselian, many families of seed ferns that characterized the Moscovian tropical wetlands had disappeared including Flemingitaceae, Diaphorodendraceae, Tedeleaceae, Urnatopteridaceae, Cyclopteridaceae, and Neurodontopteridaceae.

Labyrinthodont amphibians were particularly devastated, while the amniotes (the first members of the sauropsid and synapsid groups) fared better, being physiologically better adapted to the drier conditions.

[1] Amphibians can survive cold conditions by decreasing metabolic rates and resorting to overwintering strategies (i.e. spending most of the year inactive in burrows or under logs).

Synapsids and sauropsids acquired new niches faster than amphibians, and new feeding strategies, including herbivory and carnivory, previously only having been insectivores and piscivores.

[1] Synapsids in particular became substantially larger than before and this trend would continue until the Permian–Triassic extinction event, after which their cynodont (mammal ancestors) descendants became smaller and nocturnal.

In the latest Middle Pennsylvanian (late Moscovian) a cycle of aridification began, coinciding with abrupt faunal changes in marine and terrestrial species.

[18] This change was recorded in paleosols, which reflect a period of overall decreased hydromorphy, increased free-drainage and landscape stability, and a shift in the overall regional climate to drier conditions in the Upper Pennsylvanian (Missourian).

[22] After restoring the middle of the Skagerrak-Centered Large Igneous Province using a new reference frame, it has been shown that the Skagerrak plume rose from the core–mantle boundary to its ~300 Ma position.