Cardiac catheterization

These methods have drawbacks, but give invasive estimations of the cardiac output, which can be used to make clinical decisions (e.g., cardiogenic shock, heart failure) to improve the person's condition.

The coronary arteries are known as "epicardial vessels" as they are located in the epicardium, the outermost layer of the heart.

If necessary, the physician can utilize percutaneous coronary intervention techniques, including the use of a stent (either bare-metal or drug-eluting) to open the blocked vessel and restore appropriate blood flow.

However, in cases where multiple vessels are blocked (so-called "three-vessel disease"), the interventional cardiologist may opt instead to refer the patient to a cardiothoracic surgeon for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG; see Coronary artery bypass surgery) surgery.

The latter can be done an intensive care unit (ICU) to permit frequent measurement of the hemodynamic parameters in response to interventions.

Elevation of the Qp:Qs ratio above 1.5 to 2.0 suggests that there is a hemodynamically significant left-to-right shunt (such that the blood flow through the lungs is 1.5 to 2.0 times more than the systemic circulation).

[citation needed] A "shunt run" is often done when evaluating for a shunt by taking blood samples from superior vena cava (SVC), inferior vena cava (IVC), right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery, and system arterial.

Due to the high contrast volumes and injection pressures, this is often not performed unless other, non-invasive methods are not acceptable, not possible, or conflicting.

[citation needed] Advancements in cardiac catheterization have permitted replacement of heart valves by means of blood vessels.

This can be done in certain congenital heart diseases in which the mechanical shunting is required to sustain life such as in transposition of the great vessels.

[citation needed] Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a disease in which the myocardium is thickened and can cause blood flow obstruction.

[citation needed] Complications of cardiac catheterization and tools used during catheterization include, but not limited to:[citation needed] The likelihood of these risks depends on many factors that include the procedure being performed, the overall health state of the patient, situational (elective vs emergent), medications (e.g., anticoagulation), and more.

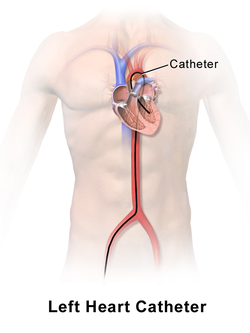

Once access is obtained, plastic catheters (tiny hollow tubes) and flexible wires are used to navigate to and around the heart.

Catheters come in numerous shapes, lengths, diameters, number of lumens, and other special features such as electrodes and balloons.

Sheaths typically have a side port that can be used to withdraw blood or injection fluids/medications, and they also have an end hole that permits introducing the catheters, wires, etc.

[citation needed] Once access is obtained, what is introduced into the vessel depends on the procedure being performed.

Clinical application of cardiac catheterization begins with Dr. Werner Forssmann in 1929, who inserted a catheter into the vein of his own forearm, guided it fluoroscopically into his right atrium, and took an X-ray picture of it.

[9] During World War II, André Frédéric Cournand, a physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, then Columbia-Bellevue, opened the first catheterization lab.

In 1956, Forssmann and Cournand were co-recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the development of cardiac catheterization.

Dr. Eugene A. Stead performed research in the 1940s, which paved the way for cardiac catheterization in the USA.