Castle

Over the Middle Ages, when genuine castles were built, they took on a great many forms with many different features, although some, such as curtain walls, arrowslits, and portcullises, were commonplace.

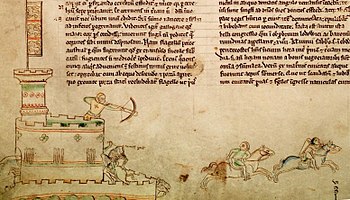

These nobles built castles to control the area immediately surrounding them and they were both offensive and defensive structures: they provided a base from which raids could be launched as well as offering protection from enemies.

While castles continued to be built well into the 16th century, new techniques to deal with improved cannon fire made them uncomfortable and undesirable places to live.

As a result, true castles went into a decline and were replaced by artillery star forts with no role in civil administration, and château or country houses that were indefensible.

[4] This contrasts with earlier fortifications, such as Anglo-Saxon burhs and walled cities such as Constantinople and Antioch in the Middle East; castles were not communal defences but were built and owned by the local feudal lords, either for themselves or for their monarch.

[15] In scholarship the castle, as defined above, is generally accepted as a coherent concept, originating in Europe and later spreading to parts of the Middle East, where they were introduced by European Crusaders.

[18] By the 16th century, when Japanese and European cultures met, fortification in Europe had moved beyond castles and relied on innovations such as the Italian trace italienne and star forts.

[29] At first, this was usual only in England, when after the Norman Conquest of 1066 the "conquerors lived for a long time in a constant state of alert";[30] elsewhere the lord's wife presided over a separate residence (domus, aula or mansio in Latin) close to the keep, and the donjon was a barracks and headquarters.

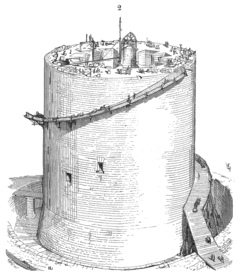

They had to be high enough to make scaling the walls with ladders difficult and thick enough to withstand bombardment from siege engines which, from the 15th century onwards, included gunpowder artillery.

[37] Provision was made in the upper storey of the gatehouse for accommodation so the gate was never left undefended, although this arrangement later evolved to become more comfortable at the expense of defence.

[48] Arrowslits, also commonly called loopholes, were narrow vertical openings in defensive walls which allowed arrows or crossbow bolts to be fired on attackers.

The Romans' own fortifications (castra) varied from simple temporary earthworks thrown up by armies on the move, to elaborate permanent stone constructions, notably the milecastles of Hadrian's Wall.

[67] A bank and ditch enclosure was a simple form of defence, and when found without an associated motte is called a ringwork; when the site was in use for a prolonged period, it was sometimes replaced by a more complex structure or enhanced by the addition of a stone curtain wall.

In the early 11th century, the motte and keep – an artificial mound with a palisade and tower on top – was the most common form of castle in Europe, everywhere except Scandinavia.

[76] While Britain, France, and Italy shared a tradition of timber construction that was continued in castle architecture, Spain more commonly used stone or mud-brick as the main building material.

[78] The Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century introduced a style of building developed in North Africa reliant on tapial, pebbles in cement, where timber was in short supply.

This has been partly attributed to the higher cost of stone-built fortifications, and the obsolescence of timber and earthwork sites, which meant it was preferable to build in more durable stone.

Although there were no scientific elements to its design, it was almost impregnable, and in 1187 Saladin chose to lay siege to the castle and starve out its garrison rather than risk an assault.

[97] During the late 11th and 12th centuries in what is now south-central Turkey the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and Templars established themselves in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, where they discovered an extensive network of sophisticated fortifications which had a profound impact on the architecture of Crusader castles.

Most of the Armenian military sites in Cilicia are characterized by: multiple bailey walls laid with irregular plans to follow the sinuosities of the outcrops; rounded and especially horseshoe-shaped towers; finely-cut often rusticated ashlar facing stones with intricate poured cores; concealed postern gates and complex bent entrances with slot machicolations; embrasured loopholes for archers; barrel, pointed or groined vaults over undercrofts, gates and chapels; and cisterns with elaborate scarped drains.

For instance, it was common in Crusader castles to have the main gate in the side of a tower and for there to be two turns in the passageway, lengthening the time it took for someone to reach the outer enclosure.

French historian François Gebelin wrote: "The great revival in military architecture was led, as one would naturally expect, by the powerful kings and princes of the time; by the sons of William the Conqueror and their descendants, the Plantagenets, when they became dukes of Normandy.

[115] The response towards more effective cannons was to build thicker walls and to prefer round towers, as the curving sides were more likely to deflect a shot than a flat surface.

[130][131] According to archaeologists Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham, "the great country houses of the seventeenth to twentieth centuries were, in a social sense, the castles of their day".

[145] Renowned designer Master James of Saint George, responsible for the construction of Beaumaris, explained the cost: In case you should wonder where so much money could go in a week, we would have you know that we have needed – and shall continue to need 400 masons, both cutters and layers, together with 2,000 less-skilled workmen, 100 carts, 60 wagons, and 30 boats bringing stone and sea coal; 200 quarrymen; 30 smiths; and carpenters for putting in the joists and floor boards and other necessary jobs.

The men's pay has been and still is very much in arrears, and we are having the greatest difficulty in keeping them because they have simply nothing to live on.Not only were stone castles expensive to build in the first place, but their maintenance was a constant drain.

[164] "The castle, as a large and imposing architectural structure in the landscape, would have evoked emotions and attachments and created a legacy for those who built it, worked in it, and lived in and around it, as well as those who simply passed it on a daily basis."

Rural castles were often associated with mills and field systems due to their role in managing the lord's estate,[175] which gave them greater influence over resources.

[181] When the Normans invaded Ireland, Scotland, and Wales in the 11th and 12th centuries, settlement in those countries was predominantly non-urban, and the foundation of towns was often linked with the creation of a castle.

Even in war, garrisons were not necessarily large as too many people in a defending force would strain supplies and impair the castle's ability to withstand a long siege.