Augustin-Louis Cauchy

A profound mathematician, Cauchy had a great influence over his contemporaries and successors;[4] Hans Freudenthal stated: Cauchy was a prolific worker; he wrote approximately eight hundred research articles and five complete textbooks on a variety of topics in the fields of mathematics and mathematical physics.

Cauchy's father was a highly ranked official in the Parisian police of the Ancien Régime, but lost this position due to the French Revolution (14 July 1789), which broke out one month before Augustin-Louis was born.

[4] On Lagrange's advice, Augustin-Louis was enrolled in the École Centrale du Panthéon, the best secondary school of Paris at that time, in the fall of 1802.

[6] Most of the curriculum consisted of classical languages; the ambitious Cauchy, being a brilliant student, won many prizes in Latin and the humanities.

In spite of these successes, Cauchy chose an engineering career, and prepared himself for the entrance examination to the École Polytechnique.

[6] One of the main purposes of this school was to give future civil and military engineers a high-level scientific and mathematical education.

After finishing school in 1810, Cauchy accepted a job as a junior engineer in Cherbourg, where Napoleon intended to build a naval base.

The Académie des Sciences was re-established in March 1816; Lazare Carnot and Gaspard Monge were removed from this academy for political reasons, and the king appointed Cauchy to take the place of one of them.

In November 1815, Louis Poinsot, who was an associate professor at the École Polytechnique, asked to be exempted from his teaching duties for health reasons.

He quit his engineering job, and received a one-year contract for teaching mathematics to second-year students of the École Polytechnique.

Riots, in which uniformed students of the École Polytechnique took an active part, raged close to Cauchy's home in Paris.

Shaken by the fall of the government and moved by a deep hatred of the liberals who were taking power, Cauchy left France to go abroad, leaving his family behind.

[10] He spent a short time at Fribourg in Switzerland, where he had to decide whether he would swear a required oath of allegiance to the new regime.

[11] In August 1833 Cauchy left Turin for Prague to become the science tutor of the thirteen-year-old Duke of Bordeaux, Henri d'Artois (1820–1883), the exiled Crown Prince and grandson of Charles X.

[12] As a professor of the École Polytechnique, Cauchy had been a notoriously bad lecturer, assuming levels of understanding that only a few of his best students could reach, and cramming his allotted time with too much material.

Further, it was believed that members of the Bureau could "forget about" the oath of allegiance, although formally, unlike the Academicians, they were obliged to take it.

For four years Cauchy was in the position of being elected but not approved; accordingly, he was not a formal member of the Bureau, did not receive payment, could not participate in meetings, and could not submit papers.

He lent his prestige and knowledge to the École Normale Écclésiastique, a school in Paris run by Jesuits, for training teachers for their colleges.

The idea came up in bureaucratic circles that it would be useful to again require a loyalty oath from all state functionaries, including university professors.

In the second paper[19] he presented the residue theorem, where the sum is over all the n poles of f(z) on and within the contour C. These results of Cauchy's still form the core of complex function theory as it is taught today to physicists and electrical engineers.

Rigor in this case meant the rejection of the principle of Generality of algebra (of earlier authors such as Euler and Lagrange) and its replacement by geometry and infinitesimals.

[22] Gilain notes that when the portion of the curriculum devoted to Analyse Algébrique was reduced in 1825, Cauchy insisted on placing the topic of continuous functions (and therefore also infinitesimals) at the beginning of the Differential Calculus.

The consensus is that Cauchy omitted or left implicit the important ideas to make clear the precise meaning of the infinitely small quantities he used.

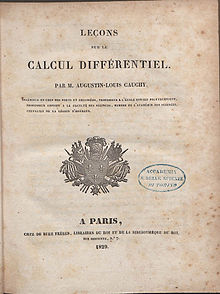

[4] He wrote a textbook[25] (see the illustration) for his students at the École Polytechnique in which he developed the basic theorems of mathematical analysis as rigorously as possible.

[26] In spite of these, Cauchy's own research papers often used intuitive, not rigorous, methods;[27] thus one of his theorems was exposed to a "counter-example" by Abel, later fixed by the introduction of the notion of uniform continuity.

In a paper published in 1855, two years before Cauchy's death, he discussed some theorems, one of which is similar to the "Principle of the argument" in many modern textbooks on complex analysis.

It took almost a century to collect all his writings into 27 large volumes: His greatest contributions to mathematical science are enveloped in the rigorous methods which he introduced; these are mainly embodied in his three great treatises: His other works include: Augustin-Louis Cauchy grew up in the house of a staunch royalist.

Their life there during that time was apparently hard; Augustin-Louis's father, Louis François, spoke of living on rice, bread, and crackers during the period.

[29] In any event, he inherited his father's staunch royalism and hence refused to take oaths to any government after the overthrow of Charles X.

Niels Henrik Abel called him a "bigoted Catholic"[31] and added he was "mad and there is nothing that can be done about him", but at the same time praised him as a mathematician.