Cellular differentiation

Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellular organism as it changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of tissues and cell types.

Differentiation dramatically changes a cell's size, shape, membrane potential, metabolic activity, and responsiveness to signals.

Metabolic composition, however, gets dramatically altered[4] where stem cells are characterized by abundant metabolites with highly unsaturated structures whose levels decrease upon differentiation.

[citation needed] Development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg and creates a single cell that has the potential to form an entire organism.

[17] Some hypothesize that dedifferentiation is an aberration that likely results in cancers,[18] but others explain it as a natural part of the immune response that was lost to humans at some point of evolution.

Based on stochastic gene expression, cellular differentiation is the result of a Darwinian selective process occurring among cells.

[21] Specifically, cell differentiation in animals is highly dependent on biomolecular condensates of regulatory proteins and enhancer DNA sequences.

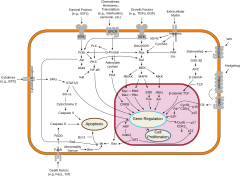

A cascade of phosphorylation reactions eventually activates a dormant transcription factor or cytoskeletal protein, thus contributing to the differentiation process in the target cell.

[23] Yamamoto and Jeffery[24] investigated the role of the lens in eye formation in cave- and surface-dwelling fish, a striking example of induction.

A clear answer to this question can be seen in the 2011 paper by Lister R, et al. [28] on aberrant epigenomic programming in human induced pluripotent stem cells.

Thus, consistent with their respective transcriptional activities,[28] DNA methylation patterns, at least on the genomic level, are similar between ESCs and iPSCs.

[29] It is thought that they achieve this through alterations in chromatin structure, such as histone modification and DNA methylation, to restrict or permit the transcription of target genes.

[29][31][32] By binding to the H3K27me2/3-tagged nucleosome, PRC1 (also a complex of PcG family proteins) catalyzes the mono-ubiquitinylation of histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119Ub1), blocking RNA polymerase II activity and resulting in transcriptional suppression.

[29] Simultaneously, differentiation and development-promoting genes are activated by Trithorax group (TrxG) chromatin regulators and lose their repression.

[32] PcG and TrxG complexes engage in direct competition and are thought to be functionally antagonistic, creating at differentiation and development-promoting loci what is termed a "bivalent domain" and rendering these genes sensitive to rapid induction or repression.

A final question to ask concerns the role of cell signaling in influencing the epigenetic processes governing differentiation.

Little direct data is available concerning the specific signals that influence the epigenome, and the majority of current knowledge about the subject consists of speculations on plausible candidate regulators of epigenetic remodeling.

[40] We will first discuss several major candidates thought to be involved in the induction and maintenance of both embryonic stem cells and their differentiated progeny, and then turn to one example of specific signaling pathways in which more direct evidence exists for its role in epigenetic change.

The Wnt pathway is involved in all stages of differentiation, and the ligand Wnt3a can substitute for the overexpression of c-Myc in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells.

[40] On the other hand, disruption of β-catenin, a component of the Wnt signaling pathway, leads to decreased proliferation of neural progenitors.

[40] Depletion of growth factors promotes the differentiation of ESCs, while genes with bivalent chromatin can become either more restrictive or permissive in their transcription.

[41] Retinoic acid can induce differentiation of human and mouse ESCs,[40] and Notch signaling is involved in the proliferation and self-renewal of stem cells.

Direct modulation of gene expression through modification of transcription factors plays a key role that must be distinguished from heritable epigenetic changes that can persist even in the absence of the original environmental signals.

Only a few examples of signaling pathways leading to epigenetic changes that alter cell fate currently exist, and we will focus on one of them.

[42] In both humans and mice, researchers showed Bmi1 to be highly expressed in proliferating immature cerebellar granule cell precursors.

When Bmi1 was knocked out in mice, impaired cerebellar development resulted, leading to significant reductions in postnatal brain mass along with abnormalities in motor control and behavior.

In order to fulfill the purpose of regenerating a variety of tissues, adult stems are known to migrate from their niches, adhere to new extracellular matrices (ECM) and differentiate.

The elasticity of the microenvironment can also affect the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs which originate in bone marrow.)

The non-muscle myosin IIa-c isoforms generates the forces in the cell that lead to signaling of early commitment markers.

[45] Researchers have achieved some success in inducing stem cell-like properties in HEK 239 cells by providing a soft matrix without the use of diffusing factors.