Tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass.

Alternatively, tile can sometimes refer to similar units made from lightweight materials such as perlite, wood, and mineral wool, typically used for wall and ceiling applications.

[1] Decorative tilework or tile art should be distinguished from mosaic, where forms are made of great numbers of tiny irregularly positioned tesserae, each of a single color, usually of glass or sometimes ceramic or stone.

Glazed and colored bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (c. 575 BC), now partly reconstructed in Berlin, with sections elsewhere.

The use of sun-dried bricks or adobe was the main method of building in Mesopotamia where river mud was found in abundance along the Tigris and Euphrates.

Rooms with tiled floors made of clay decorated with geometric circular patterns have been discovered from the ancient remains of Kalibangan, Balakot and Ahladino[3][4] Tiling was used in the second century by the Sinhalese kings of ancient Sri Lanka, using smoothed and polished stone laid on floors and in swimming pools.

[6] The succeeding Sassanid Empire used tiles patterned with geometric designs, flowers, plants, birds and human beings, glazed up to a centimeter thick.

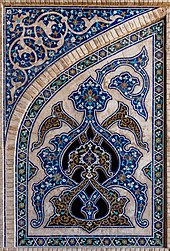

[6] Early Islamic mosaics in Iran consist mainly of geometric decorations in mosques and mausoleums, made of glazed brick.

In the moraq technique, single-color tiles were cut into small geometric pieces and assembled by pouring liquid plaster between them.

The 14th-century mihrab at Madrasa Imami in Isfahan is an outstanding example of aesthetic union between the Islamic calligrapher's art and abstract ornament.

A wide variety of tiles had to be manufactured in order to cover complex forms of the hall with consistent mosaic patterns.

[6] The seven colors of Haft Rang tiles were usually black, white, ultramarine, turquoise, red, yellow and fawn.

The Persianate tradition continued and spread to much of the Islamic world, notably the İznik pottery of Turkey under the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The zellige tradition of Arabic North Africa uses small colored tiles of various shapes to make very complex geometric patterns.

The imaginary tiles with Old Testament scenes shown on the floor in Jan van Eyck's 1434 Annunciation in Washington are an example.

The Baroque period produced extremely large painted scenes on tiles, usually in blue and white, for walls.

Wall tiles in various styles also revived; the rise of the bathroom contributing greatly to this, as well as greater appreciation of the benefit of hygiene in kitchens.

[10] Portugal and São Luís continue their tradition of azulejo tilework today, with tiles used to decorate buildings, ships,[11] and even rocks.

With exceptions, notably the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, decorated tiles or glazed bricks do not feature largely in East Asian ceramics.

Over time some cultures, notably in Asia, began to apply glazes to clay tiles, achieving a wide variety of colors and combinations.

Modern clay roof tiles typically source their color from kiln firing conditions, the application of glaze, or the use of a ceramic engobe.

Floor tiles are typically set into mortar consisting of sand, Portland cement and often a latex additive.

Granite or marble tiles are sawn on both sides and then polished or finished on the top surface so that they have a uniform thickness.

The tendency of floor tiles to stain depends not only on a sealant being applied, and periodically reapplied, but also on their porosity or how porous the stone is.

They are placed in an aluminium grid; they provide little thermal insulation but are generally designed either to improve the acoustics of a room or to reduce the volume of air being heated or cooled.

Breaking, displacing, or removing ceiling tiles enables hot gases and smoke from a fire to rise and accumulate above detectors and sprinklers.

[19] The ANSI defines as "a ceramic tile that has 'a water absorption of 0.5%' or less.” It is made generally by the pressed or extruded method.

Specialized custom-tile printing techniques permit transfer under heat and pressure or the use of high temperature kilns to fuse the picture to the tile substrate.

This has become a method of producing custom tile murals for kitchens, showers, and commercial decoration in restaurants, hotels, and corporate lobbies.

[22] Recent technology applied to Digital ceramic and porcelain printers allow images to be printed with a wider color gamut and greater color stability even when fired in a kiln up to 2200 °F A method for custom tile printing involving a diamond-tipped drill controlled by a computer.