Cerebellum

Its cortical surface is covered with finely spaced parallel grooves, in striking contrast to the broad irregular convolutions of the cerebral cortex.

These parallel grooves conceal the fact that the cerebellar cortex is actually a thin, continuous layer of tissue tightly folded in the style of an accordion.

This complex neural organization gives rise to a massive signal-processing capability, but almost all of the output from the cerebellar cortex passes through a set of small deep nuclei lying in the white matter interior of the cerebellum.

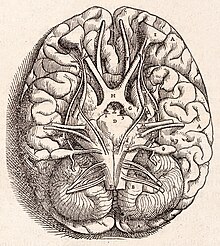

[8] At the level of gross anatomy, the cerebellum consists of a tightly folded layer of cortex, with white matter underneath and a fluid-filled ventricle at the base.

At an intermediate level, the cerebellum and its auxiliary structures can be separated into several hundred or thousand independently functioning modules called "microzones" or "microcompartments".

[10] It is separated from the overlying cerebrum by a layer of leathery dura mater, the cerebellar tentorium; all of its connections with other parts of the brain travel through the pons.

[12] The unusual surface appearance of the cerebellum conceals the fact that most of its volume is made up of a very tightly folded layer of gray matter: the cerebellar cortex.

Embedded within the white matter—which is sometimes called the arbor vitae (tree of life) because of its branched, tree-like appearance in cross-section—are four deep cerebellar nuclei, composed of gray matter.

It is the oldest part in evolutionary terms (archicerebellum) and participates mainly in balance and spatial orientation; its primary connections are with the vestibular nuclei, although it also receives visual and other sensory input.

It receives proprioceptive input from the dorsal columns of the spinal cord (including the spinocerebellar tract) and from the cranial trigeminal nerve, as well as from visual and auditory systems.

[15] It sends fibers to deep cerebellar nuclei that, in turn, project to both the cerebral cortex and the brain stem, thus providing modulation of descending motor systems.

After emitting collaterals that affect nearby parts of the cortex, their axons travel into the deep cerebellar nuclei, where they make on the order of 1,000 contacts each with several types of nuclear cells, all within a small domain.

Because granule cells are so small and so densely packed, it is difficult to record their spike activity in behaving animals, so there is little data to use as a basis for theorizing.

Although the inferior olive lies in the medulla oblongata and receives input from the spinal cord, brainstem and cerebral cortex, its output goes entirely to the cerebellum.

For the majority of researchers, the climbing fibers signal errors in motor performance, either in the usual manner of discharge frequency modulation or as a single announcement of an 'unexpected event'.

The dentate nucleus, which in mammals is much larger than the others, is formed as a thin, convoluted layer of gray matter, and communicates exclusively with the lateral parts of the cerebellar cortex.

[11] The majority of neurons in the deep nuclei have large cell bodies and spherical dendritic trees with a radius of about 400 μm, and use glutamate as their neurotransmitter.

Intermixed with them are a lesser number of small cells, which use GABA as a neurotransmitter and project exclusively to the inferior olivary nucleus, the source of climbing fibers.

[28] Thus, as the adjoining diagram illustrates, Purkinje cell dendrites are flattened in the same direction as the microzones extend, while parallel fibers cross them at right angles.

[28] In 2005, Richard Apps and Martin Garwicz summarized evidence that microzones themselves form part of a larger entity they call a multizonal microcomplex.

[43] Although a full understanding of cerebellar function has remained elusive, at least four principles have been identified as important: (1) feedforward processing, (2) divergence and convergence, (3) modularity, and (4) plasticity.

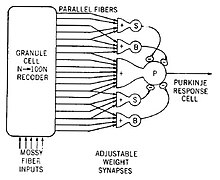

[45] Most theories that assign learning to the circuitry of the cerebellum are derived from the ideas of David Marr[27] and James Albus,[7] who postulated that climbing fibers provide a teaching signal that induces synaptic modification in parallel fiber–Purkinje cell synapses.

Studies of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (which stabilizes the visual image on the retina when the head turns) found that climbing fiber activity indicated "retinal slip", although not in a very straightforward way.

The original theory put forth by Braitenberg and Roger Atwood in 1958 proposed that slow propagation of signals along parallel fibers imposes predictable delays that allow the cerebellum to detect time relationships within a certain window.

Albus also formulated his version as a software algorithm he called a CMAC (Cerebellar Model Articulation Controller), which has been tested in a number of applications.

Damage to the flocculonodular lobe may show up as a loss of equilibrium and in particular an altered, irregular walking gait, with a wide stance caused by difficulty in balancing.

[57] The list of medical problems that can produce cerebellar damage is long, including stroke, hemorrhage, swelling of the brain (cerebral edema), tumors, alcoholism, physical trauma such as gunshot wounds or explosives, and chronic degenerative conditions such as olivopontocerebellar atrophy.

[68] Mutations that abnormally activate Sonic hedgehog signaling predispose to cancer of the cerebellum (medulloblastoma) in humans with Gorlin Syndrome and in genetically engineered mouse models.

[81] The only cerebellum-like structure found in mammals is the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), one of the two primary sensory nuclei that receive input directly from the auditory nerve.

One of the brain areas that receives primary input from the lateral line organ, the medial octavolateral nucleus, has a cerebellum-like structure, with granule cells and parallel fibers.