Charon's obol

[4] The phrase "Charon's obol" as used by archaeologists sometimes can be understood as referring to a particular religious rite, but often serves as a kind of shorthand for coinage as grave goods presumed to further the deceased's passage into the afterlife.

"[26] In an elegy of consolation spoken in the person of the dead woman, the Augustan poet Propertius expresses the finality of death by her payment of the bronze coin to the infernal toll collector (portitor).

The investigating archaeologists did not regard the practice as typical of the region, but speculate that the local geography lent itself to adapting the Greek myth, as bodies of the dead in actuality had to be ferried across a river from the town to the cemetery.

[53] Although the placement of a coin within the skull is uncommon in Jewish antiquity and was potentially an act of idolatry, rabbinic literature preserves an allusion to Charon in a lament for the dead "tumbling aboard the ferry and having to borrow his fare."

At one time, the cemetery was regarded as exhibiting two distinct phases: an earlier Gallo-Roman period when the dead were buried with vessels, notably of glass, and Charon's obol; and later, when they were given funerary dress and goods according to Frankish custom.

"The varied placement of coins of different values ... demonstrates at least partial if not complete loss of understanding of the original religious function of Charon’s obol," remarks Bonnie Effros, a specialist in Merovingian burial customs.

[59] A gold-plated coin was found in the mouth of a young man buried on the Isle of Wight in the mid-6th century; his other grave goods included vessels, a drinking horn, a knife, and gaming-counters[60] of ivory with one cobalt-blue glass piece.

A function comparable to that of Charon's obol is suggested by examples such as a man's burial at Monkton in Kent and a group of several male graves on Gotland, Sweden, for which the bracteate was deposited in a pouch beside the body.

[62] According to one interpretation, the purse-hoard in the Sutton Hoo ship burial (Suffolk, East Anglia), which contained a variety of Merovingian gold coins, unites the traditional Germanic voyage to the afterlife with "an unusually splendid form of Charon's obol."

A fragment of 6th century BC pottery has been interpreted as Charon sitting in the stern as steersman of a boat fitted with ten pairs of oars and rowed by eidola (εἴδωλα), shades of the dead.

[75] These examples of the "Charon's piece" resemble in material and size the tiny inscribed tablet or funerary amulet called a lamella (Latin for a metal-foil sheet) or a Totenpass, a "passport for the dead" with instructions on navigating the afterlife, conventionally regarded as a form of Orphic or Dionysiac devotional.

They appear to have been sewn onto the deceased's garment just before burial, not worn during life,[86] and in this practice are comparable to the pierced Roman coins found in Anglo-Saxon graves that were attached to clothing instead of or in addition to being threaded onto a necklace.

Some scholars have speculated that they are a form of "temple money" or votive offering,[94] but Sharon Ratke has suggested that they might represent good wishes for travelers, perhaps as a metaphor for the dead on their journey to the otherworld,[95] especially those depicting "wraiths.

"[96] Ships often appear in Greek and Roman funerary art representing a voyage to the Isles of the Blessed, and a 2nd-century sarcophagus found in Velletri, near Rome, included Charon's boat among its subject matter.

[97] In modern-era Greek folkloric survivals of Charon (as Charos the death demon), sea voyage and river crossing are conflated, and in one later tale, the soul is held hostage by pirates, perhaps representing the oarsmen, who require a ransom for release.

[105] Because of the diversity of religious beliefs in the Greco-Roman world, and because the mystery religions that were most concerned with the afterlife and soteriology placed a high value on secrecy and arcane knowledge, no single theology[106] has been reconstructed that would account for Charon's obol.

For the Greeks, Pluto (Ploutōn, Πλούτων), the ruler of the dead and the consort of Persephone, became conflated with Plutus (Ploutos, Πλοῦτος), wealth personified; Plato points out the meaningful ambiguity of this etymological play in his dialogue Cratylus.

[113] The obscure goddess Angerona, whose iconography depicted silence and secrecy,[114] and whose festival followed that of Ops, seems to have regulated communications between the realm of the living and the underworld;[115] she may have been a guardian of both arcane knowledge and stored, secret wealth.

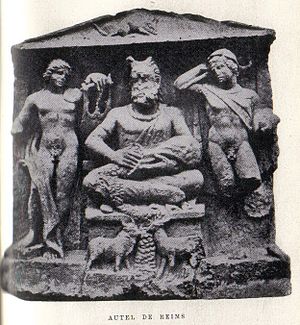

[122] On a relief from the Gallic civitas of the Remi,[123] the god holds in his lap a sack or purse, the contents of which – identified by scholars variably as coins or food (grain, small fruits, or nuts)[124] – may be intentionally ambiguous in expressing desired abundance.

[125] In his best-known representation, on the problematic Gundestrup Cauldron, he is surrounded by animals with mythico-religious significance; taken in the context of an accompanying scene of initiation, the horned god can be interpreted as presiding over the process of metempsychosis, the cycle of death and rebirth,[126] regarded by ancient literary sources as one of the most important tenets of Celtic religion[127] and characteristic also of Pythagoreanism and the Orphic or Dionysiac mysteries.

The Phrygian king's famous "golden touch" was a divine gift from Dionysus, but its acceptance separated him from the human world of nourishment and reproduction: both his food and his daughter were transformed by contact with him into immutable, unreciprocal gold.

[144] "Charon's obol" is often found in burials with objects or inscriptions indicative of mystery cult, and the coin figures in a Latin prose narrative that alludes to initiation ritual, the "Cupid and Psyche" story from the Metamorphoses of Apuleius.

The tale lends itself to multiple interpretational approaches, and it has frequently been analyzed as an allegory of Platonism as well as of religious initiation, iterating on a smaller scale the plot of the Metamorphoses as a whole, which concerns the protagonist Lucius's journey towards salvation through the cult of Isis.

[145] Ritual elements were associated with the story even before Apuleius's version, as indicated in visual representations; for instance, a 1st-century BC sardonyx cameo depicting the wedding of Cupid and Psyche shows an attendant elevating a liknon (basket) used in Dionysiac initiation.

[158]With instructions that recall those received by Psyche for her heroic descent, or the inscribed Totenpass for initiates, the Christian protagonist of a 14th-century French pilgrimage narrative is advised: This bread (pain, i.e. the Eucharist) is most necessary for the journey you have to make.

[171] The kern of the title is an otherworldly trickster figure who performs a series of miracles; after inducing twenty armed men to kill each other, he produces herbs from his bag and instructs his host's gatekeeper to place them within the jaws of each dead man to bring him back to life.

The placement suggests a functional equivalence with the Goldblattkreuze and the Orphic gold tablets; its purpose — to assure the deceased's successful passage to the afterlife — is analogous to that of Charon's obol and the Totenpässe of mystery initiates, and in this case it acts also as a seal to block the dead from returning to the world of the living.

[182] In a general audience October 24, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI quoted Paulinus's account of the death of St. Ambrose, who received and swallowed the corpus Domini and immediately "gave up his spirit, taking the good Viaticum with him.

[187] A century after Heinrici, James Downey examined the funerary practices of Christian Corinthians in historical context and argued that they intended vicarious baptism to protect the deceased's soul against interference on the journey to the afterlife.

Irish Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney makes a less direct allusion with a simile — "words imposing on my tongue like obols" — in the "Fosterage" section of his long poem Singing School:[195] The speaker associates himself with the dead, bearing payment for Charon the ferryman, to cross the river Styx.