Charts on SO(3)

It is also closely related (double covered) with the set of quaternions with their internal product, as well as to the set of rotation vectors (though here the relation is harder to describe, see below for details), with a different internal composition operation given by the product of their equivalent matrices.

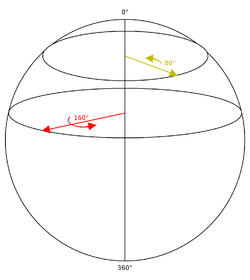

Continuing southward, the radii of the circles now become smaller (corresponding to the absolute value of the angle of the rotation considered as a negative number).

This set of expanding and contracting spheres represents a hypersphere in four-dimensional space (a 3-sphere).

This behavior is matched by the set of unit quaternions: A general quaternion represents a point in a four-dimensional space, but constraining it to have unit magnitude yields a three-dimensional space equivalent to the surface of a hypersphere.

The point (w,x,y,z) represents a rotation around the axis directed by the vector (x,y,z) by an angle This problem is similar to parameterize the bidimensional surface of a sphere with two coordinates, such as latitude and longitude.

The possible parametrizations candidates include: There are problems in using these as more than local charts, to do with their multiple-valued nature, and singularities.

Problems of this sort are inevitable, since SO(3) is diffeomorphic to real projective space P3(R), which is a quotient of S3 by identifying antipodal points, and charts try to model a manifold using R3.

gimbal lock), while the quaternion representation is always a double cover, with q and −q giving the same rotation.

It is possible to restrict these matrices to a ball around the origin in R3 so that rotations do not exceed 180 degrees, and this will be one-to-one, except for rotations by 180 degrees, which correspond to the boundary S2, and these identify antipodal points – this is the cut locus.

A similar situation holds for applying a Cayley transform to the skew-symmetric matrix.

But since rotations around n and −n are parameterized by opposite values of θ, the result is an S1 bundle over P2(R), which turns out to be P3(R).

Fractional linear transformations use four complex parameters, a, b, c, and d, with the condition that ad−bc is non-zero.

This suggests writing (a,b,c,d) as a 2 × 2 complex matrix of determinant 1, that is, as an element of the special linear group SL(2,C).

In some cases, we need to remember that certain parameter values result in the same rotation, and to remove this issue, boundaries must be set up, but then a path through this region in R3 must then suddenly jump to a different region when it crosses a boundary.

The quaternion representation has none of these problems (being a two-to-one mapping everywhere), but it has 4 parameters with a condition (unit length), which sometimes makes it harder to see the three degrees of freedom available.

The translational part can be decoupled from the rotational part in standard Newtonian kinematics by considering the motion of the center of mass, and rotations of the rigid body about the center of mass.

Therefore, any rigid body movement leads directly to SO(3), when we factor out the translational part.

Now we have an ordinary closed loop on the surface of the ball, connecting the north pole to itself along a great circle.

In physics applications, the non-triviality of the fundamental group allows for the existence of objects known as spinors, and is an important tool in the development of the spin–statistics theorem.

The map from S3 onto SO(3) that identifies antipodal points of S3 is a surjective homomorphism of Lie groups, with kernel {±1}.