Chemical industry

Central to the modern world economy, it converts raw materials (oil, natural gas, air, water, metals, and minerals) into commodity chemicals for industrial and consumer products.

John Roebuck and Samuel Garbett were the first to establish a large-scale factory in Prestonpans, Scotland, in 1749, which used leaden condensing chambers for the manufacture of sulfuric acid.

[1][2] In the early 18th century, cloth was bleached by treating it with stale urine or sour milk and exposing it to sunlight for long periods of time, which created a severe bottleneck in production.

Sulfuric acid began to be used as a more efficient agent as well as lime by the middle of the century, but it was the discovery of bleaching powder by Charles Tennant that spurred the creation of the first great chemical industrial enterprise.

His powder was made by reacting chlorine with dry slaked lime and proved to be a cheap and successful product.

By the 18th century, this source was becoming uneconomical due to deforestation, and the French Academy of Sciences offered a prize of 2400 livres for a method to produce alkali from sea salt (sodium chloride).

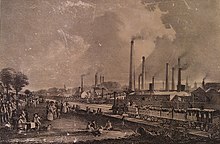

These huge factories began to produce a greater diversity of chemicals as the Industrial Revolution matured.

Originally, large quantities of alkaline waste were vented into the environment from the production of soda, provoking one of the first pieces of environmental legislation to be passed in 1863.

The coal tar and ammoniacal liquor residues of coal gas manufacture for gas lighting began to be processed in 1822 at the Bonnington Chemical Works in Edinburgh to make naphtha, pitch oil (later called creosote), pitch, lampblack (carbon black) and sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride).

Production of artificial manufactured fertilizer for agriculture was pioneered by Sir John Lawes at his purpose-built Rothamsted Research facility.

Processes for the vulcanization of rubber were patented by Charles Goodyear in the United States and Thomas Hancock in England in the 1840s.

He partly transformed aniline into a crude mixture which, when extracted with alcohol, produced a substance with an intense purple colour.

[8] The petrochemical industry can be traced back to the oil works of Scottish chemist James Young, and Canadian Abraham Pineo Gesner.

[11] Major industrial customers include rubber and plastic products, textiles, apparel, petroleum refining, pulp and paper, and primary metals.

The major markets for plastics are packaging, followed by home construction, containers, appliances, pipe, transportation, toys, and games.

Life sciences (about 30% of the dollar output of the chemistry business) include differentiated chemical and biological substances, pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, animal health products, vitamins, and pesticides.

While much smaller in volume than other chemical sectors, their products tend to have high prices – over ten dollars per pound – growth rates of 1.5 to 6 times GDP, and research and development spending at 15 to 25% of sales.

Life science products are usually produced with high specifications and are closely scrutinized by government agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration.

Pesticides, also called "crop protection chemicals", are about 10% of this category and include herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides.

Inorganic chemicals tend to be the largest volume but much smaller in dollar revenue due to their low prices.

[citation needed] The largest chemical producers today are global companies with international operations and plants in numerous countries.

Solvents, pesticides, lye, washing soda, and portland cement provide a few examples of products used by consumers.

The industry includes manufacturers of inorganic- and organic-industrial chemicals, ceramic products, petrochemicals, agrochemicals, polymers and rubber (elastomers), oleochemicals (oils, fats, and waxes), explosives, fragrances and flavors.

Related industries include petroleum, glass, paint, ink, sealant, adhesive, pharmaceuticals and food processing.

More organizations within the industry are implementing chemical compliance software to maintain quality products and manufacturing standards.

[16] The products are packaged and delivered by many methods, including pipelines, tank-cars, and tank-trucks (for both solids and liquids), cylinders, drums, bottles, and boxes.

The petrochemical and commodity chemical manufacturing units are on the whole single product continuous processing plants.

The chemical industry is also the second largest consumer of energy in manufacturing and spends over $5 billion annually on pollution abatement.

Though the business of chemistry is worldwide in scope, the bulk of the world's $3.7 trillion chemical output is accounted for by only a handful of industrialized nations.