Chinese numerals

The more familiar indigenous system is based on Chinese characters that correspond to numerals in the spoken language.

Most people and institutions in China primarily use the Arabic or mixed Arabic-Chinese systems for convenience, with traditional Chinese numerals used in finance, mainly for writing amounts on cheques, banknotes, some ceremonial occasions, some boxes, and on commercials.

Similar to spelling-out numbers in English (e.g., "one thousand nine hundred forty-five"), it is not an independent system per se.

Since it reflects spoken language, it does not use the positional system as in Arabic numerals, in the same way that spelling out numbers in English does not.

For numbers larger than 10,000, similarly to the long and short scales in the West, there have been four systems in ancient and modern usage.

The original one, with unique names for all powers of ten up to the 14th, is ascribed to the Yellow Emperor in the 6th century book by Zhen Luan, Wujing suanshu; 'Arithmetic in Five Classics'.

In practice, this situation does not lead to ambiguity, with the exception of 兆; zhào, which means 1012 according to the system in common usage throughout the Chinese communities as well as in Japan and Korea, but has also been used for 106 in recent years (especially in mainland China for megabyte).

To avoid problems arising from the ambiguity, the PRC government never uses this character in official documents, but uses 万亿; wànyì) or 太; tài; 'tera-' instead.

Partly due to this, combinations of 万 and 亿 are often used instead of the larger units of the traditional system as well, for example 亿亿; yìyì instead of 京.

The larger (兆, 京, 垓, 秭, 穰) and smaller Chinese numerals (微, 纖, 沙, 塵, 渺) were defined as translation for the SI prefixes as mega, giga, tera, peta, exa, micro, nano, pico, femto, atto, resulting in the creation of yet more values for each numeral.

In the southern Min dialect of Chaozhou (Teochew), 兩 (no6) is used to represent the "2" numeral in all numbers from 200 onwards.

Thus: Notes: In certain older texts like the Protestant Bible, or in poetic usage, numbers such as 114 may be written as [100] [10] [4] (百十四).

This is used both officially and unofficially, and come in a variety of styles: Interior zeroes before the unit position (as in 1002) must be spelt explicitly.

Thus: To construct a fraction, the denominator is written first, followed by 分; fēn; 'part', then the literary possessive particle 之; zhī; 'of this', and lastly the numerator.

百bǎi100分fēnparts之zhīof this二èr2十shí10五wǔ5百 分 之 二 十 五bǎi fēn zhī èr shí wǔ100 parts {of this} 2 10 5百bǎi100分fēnparts之zhīof this一yī1百bǎi100一yī1十shí10百 分 之 一 百 一 十bǎi fēn zhī yī bǎi yī shí100 parts {of this} 1 100 1 10Because percentages and other fractions are formulated the same, Chinese are more likely than not to express 10%, 20% etc.

In Taiwan, the most common formation of percentages in the spoken language is the number per hundred followed by the word 趴; pā, a contraction of the Japanese パーセント; pāsento, itself taken from 'percent'.

十shí10六liù6點diǎnpoint九jiǔ9八bā8十 六 點 九 八shí liù diǎn jiǔ bā10 6 point 9 8一yī1萬wàn10000兩liǎng2千qiān1000三sān3百bǎi100四sì4十shí10五wǔ5點diǎnpoint六liù6七qī7八bā8九jiǔ9一 萬 兩 千 三 百 四 十 五 點 六 七 八 九yī wàn liǎng qiān sān bǎi sì shí wǔ diǎn liù qī bā jiǔ1 10000 2 1000 3 100 4 10 5 point 6 7 8 9七七qī7十十shí10五五wǔ5點點diǎnpoint四四sì4〇零líng0二二èr2五五wǔ5七 十 五 點 四 〇 二 五七 十 五 點 四 零 二 五qī shí wǔ diǎn sì líng èr wǔ7 10 5 point 4 0 2 5零líng0點diǎnpoint一yī1零 點 一líng diǎn yī0 point 1半; bàn; 'half' functions as a number and therefore requires a measure word.

負fùnegative一yī1千qiān1000一yī1百bǎi100五wǔ5十shí10八bā8負 一 千 一 百 五 十 八fù yī qiān yī bǎi wǔ shí bānegative 1 1000 1 100 5 10 8負fùnegative三sān3又yòuand六liù6分fēnparts之zhīof this五wǔ5負 三 又 六 分 之 五fù sān yòu liù fēn zhī wǔnegative 3 and 6 parts {of this} 5負fùnegative七qī7十shí10五wǔ5點diǎnpoint四sì4零líng0二èr2五wǔ5負 七 十 五 點 四 零 二 五fù qī shí wǔ diǎn sì líng èr wǔnegative 7 10 5 point 4 0 2 5Chinese grammar requires the use of classifiers (measure words) when a numeral is used together with a noun to express a quantity.

There is only one exception: Sunday is 星期日; xīngqīrì, or informally 星期天; xīngqītiān, both literally "week day".

[14] Full dates are usually written in the format 2001年1月20日 for January 20, 2001 (using 年; nián "year", 月; yuè "month", and 日; rì "day") – all the numbers are read as cardinals, not ordinals, with no leading zeroes, and the year is read as a sequence of digits.

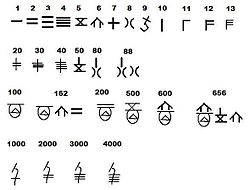

Nowadays, the huāmǎ system is only used for displaying prices in Chinese markets or on traditional handwritten invoices.

While the five digits on one hand can easily express the numbers one to five, six to ten have special signs that can be used in commerce or day-to-day communication.

In early civilizations, the Shang were able to express any numbers, however large, with only nine symbols and a counting board though it was still not positional.

[nb 3] Alexander Wylie, Christian missionary to China, in 1853 already refuted the notion that "the Chinese numbers were written in words at length", and stated that in ancient China, calculation was carried out by means of counting rods, and "the written character is evidently a rude presentation of these".

After being introduced to the rod numerals, he said "Having thus obtained a simple but effective system of figures, we find the Chinese in actual use of a method of notation depending on the theory of local value [i.e. place-value], several centuries before such theory was understood in Europe, and while yet the science of numbers had scarcely dawned among the Arabs.