Chinese room

[1] Before Searle, similar arguments had been presented by figures including Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1714), Anatoly Dneprov (1961), Lawrence Davis (1974) and Ned Block (1978).

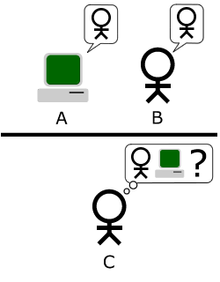

[3] The thought experiment starts by placing a computer that can perfectly converse in Chinese in one room, and a human that only knows English in another, with a door separating them.

The argument is directed against the philosophical positions of functionalism and computationalism,[4] which hold that the mind may be viewed as an information-processing system operating on formal symbols, and that simulation of a given mental state is sufficient for its presence.

"The overwhelming majority", notes Behavioral and Brain Sciences editor Stevan Harnad,[e] "still think that the Chinese Room Argument is dead wrong".

[15] Although the Chinese Room argument was originally presented in reaction to the statements of artificial intelligence researchers, philosophers have come to consider it as an important part of the philosophy of mind.

[23] Simon, together with Allen Newell and Cliff Shaw, after having completed the first program that could do formal reasoning (the Logic Theorist), claimed that they had "solved the venerable mind–body problem, explaining how a system composed of matter can have the properties of mind.

Goldstein and Levinstein explore whether large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can possess minds, focusing on their ability to exhibit folk psychology, including beliefs, desires, and intentions.

Additionally, they refute common skeptical challenges, such as the "stochastic parrots" argument and concerns over memorization, asserting that LLMs exhibit structured internal representations that align with these philosophical criteria.

These hallucinations, though arising from accurate functional representations, underscore the gap between computational reliability and the ontological complexity of human mental states.

[36] David Chalmers suggests that while current LLMs lack features like recurrent processing and unified agency, advancements in AI could address these limitations within the next decade, potentially enabling systems to achieve consciousness.

This perspective challenges Searle's original claim that purely "syntactic" processing cannot yield understanding or consciousness, arguing instead that such systems could have authentic mental states.

Biological naturalism implies that one cannot determine if the experience of consciousness is occurring merely by examining how a system functions, because the specific machinery of the brain is essential.

[41][j] Searle's biological naturalism and strong AI are both opposed to Cartesian dualism,[40] the classical idea that the brain and mind are made of different "substances".

[43] Colin McGinn argues that the Chinese room provides strong evidence that the hard problem of consciousness is fundamentally insoluble.

The Chinese room argument leaves open the possibility that a digital machine could be built that acts more intelligently than a person, but does not have a mind or intentionality in the same way that brains do.

Turing then considered each possible objection to the proposal "machines can think", and found that there are simple, obvious answers if the question is de-mystified in this way.

"[50][51] The Chinese room argument does not refute this, because it is framed in terms of "intelligent action", i.e. the external behavior of the machine, rather than the presence or absence of understanding, consciousness and mind.

[28] There are some critics, such as Hanoch Ben-Yami, who argue that the Chinese room cannot simulate all the abilities of a digital computer, such as being able to determine the current time.

[l] He begins with three axioms: Searle posits that these lead directly to this conclusion: This much of the argument is intended to show that artificial intelligence can never produce a machine with a mind by writing programs that manipulate symbols.

Eliminative materialists reject A2, arguing that minds don't actually have "semantics"—that thoughts and other mental phenomena are inherently meaningless but nevertheless function as if they had meaning.

[73][q] Hans Moravec comments: "If we could graft a robot to a reasoning program, we wouldn't need a person to provide the meaning anymore: it would come from the physical world.

"[77] Some respond that the room, as Searle describes it, is connected to the world: through the Chinese speakers that it is "talking" to and through the programmers who designed the knowledge base in his file cabinet.

Searle's critics argue that there would be no point during the procedure when he can claim that conscious awareness ends and mindless simulation begins.

Ned Block's Blockhead argument[95] suggests that the program could, in theory, be rewritten into a simple lookup table of rules of the form "if the user writes S, reply with P and goto X".

It is hard to visualize that an instant of one's conscious experience can be captured in a single large number, yet this is exactly what "strong AI" claims.

"[98] Some of the arguments above also function as appeals to intuition, especially those that are intended to make it seem more plausible that the Chinese room contains a mind, which can include the robot, commonsense knowledge, brain simulation and connectionist replies.

[100] Several critics point out that the man in the room would probably take millions of years to respond to a simple question, and would require "filing cabinets" of astronomical proportions.

They propose this analogous thought experiment: "Consider a dark room containing a man holding a bar magnet or charged object.

If eliminative materialism is the correct scientific account of human cognition then the assumption of the Chinese room argument that "minds have mental contents (semantics)" must be rejected.

[118] Steven Pinker suggested that a response to that conclusion would be to make a counter thought experiment to the Chinese Room, where the incredulity goes the other way.