Circumflex in French

The circumflex, called accent circonflexe, has three primary functions in French: And in certain words, it is simply an orthographic convention.

Grammarian Jacques Dubois (known as Sylvius) is the first writer known to have used the Greek symbol in his writing (although he wrote in Latin).

Several grammarians of the French Renaissance attempted to prescribe a precise usage for the diacritic in their treatises on language.

He justifies its usage in his work Iacobii Sylvii Ambiani In Linguam Gallicam Isagoge una, cum eiusdem Grammatica Latinogallica ex Hebraeis Graecis et Latinus authoribus (An Introduction to the Gallic (French) Language, And Its Grammar With Regard to Hebrew, Latin and Greek Authors) published by Robert Estienne in 1531.

, or, in Latin, maius, plenus, mihi, mei, causa, flos, pro.Sylvius was quite aware that the circumflex was purely a graphical convention.

When two adjacent vowels were to be pronounced independently, Sylvius proposed using the diaeresis, called the tréma in French.

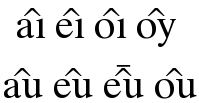

Even these groups, however, did not represent true diphthongs (such as the English try /traɪ/), but rather adjacent vowels pronounced separately without an intervening consonant.

As French no longer had any true diphthongs, the diaeresis alone would have sufficed to distinguish between ambiguous vowel pairs.

Étienne Dolet, in his Maniere de bien traduire d'une langue en aultre : d'aduantage de la punctuation de la langue Francoyse, plus des accents d'ycelle (1540),[2] uses the circumflex (this time as a punctuation mark written between two letters) to show three metaplasms: Thus Dolet uses the circumflex to indicate lost or silent phonemes, one of the uses for which the diacritic is still used today.

Dolet summarized his own contributions with these words: "Ce ſont les preceptions" [préceptes], "que tu garderas quant aux accents de la langue Francoyse.

Leſquels auſsi obſerueront tous diligents Imprimeurs : car telles choſes enrichiſſent fort l'impreſsion, & demõſtrent" [démontrent], "que ne faiſons rien par ignorance."

All diligent printers should also observe these rules, because such things greatly enrich printing and demonstrate that nothing is left to chance."

In many cases, the circumflex indicates the historical presence of a phoneme which over the course of linguistic evolution became silent, and then disappeared altogether from the orthography.

Around the time of the Battle of Hastings in 1066, such post-vocalic /s/ sounds had begun to disappear before hard consonants in many words, being replaced by a compensatory elongation of the preceding vowel, which was maintained into the 18th century.

The silent /s/ remained orthographically for some time, and various attempts were made to distinguish the historical presence graphically, but without much success.

Notably, 17th century playwright Pierre Corneille, in printed editions of his plays, used the "long s" (ſ) to indicate silent "s" and the traditional form for the /s/ sound when pronounced (tempeſte, haſte, teſte vs. peste, funeste, chaste).

For example: More examples of a disappearing 's' that has been marked with an accent circumflex can be seen in the words below: Here are some instances where French has lost an S but other Romance Languages have not: The circumflex also serves as a vestige of other lost letters, particularly letters in hiatus where two vowels have contracted into one phoneme, such as aage → âge; baailler → bâiller, etc.

Likewise, the former medieval diphthong "eu" when pronounced /y/ would often, in the 18th century, take a circumflex in order to distinguish homophones, such as deu → dû (from devoir vs. du = de + le); creu → crû (from croître vs. cru from croire) ; seur → sûr (the adjective vs. the preposition sur), etc.

This rule is sporadic, because many such words are written without the circumflex; for instance, axiome and zone have unaccented vowels despite their etymology (Greek ἀξίωμα and ζώνη) and pronunciation (/aksjom/, /zon/).

On the other hand, many learned words ending in -ole, -ome, and -one (but not tracing back to a Greek omega) acquired a circumflex accent and the closed /o/ pronunciation by analogy with words like cône and diplôme: trône (θρόνος), pôle (πόλος), binôme (from Latin binomium).

The circumflex accent was also used to indicate French vowels deriving from Greek eta (η), but this practice has not always survived in modern orthography.

[citation needed] It is thought to give words an air of prestige, like a crown (thus suprême and voûte).

In general, vowels bearing the circumflex accent were historically long (for example, through compensatory lengthening associated with the consonant loss described above).

[4] The circumflex does not affect the pronunciation of the letters "i" or "u" (except in the combination "eû": jeûne [ʒøn] vs. jeune [ʒœn]).

The diacritic disappears in related words if the pronunciation changes (particularly when the vowel in question is no longer in the stressed final syllable).

For instance, in non-final syllables, "ê" can be realized as a closed /e/ as a result of vowel harmony: compare bête /bɛt/ and bêta /bɛta/ with bêtise /betiz/ and abêtir [abetiʁ], or tête /tɛt/ and têtard /tɛtaʁ/ vs. têtu /tety/.

[5] In varieties of French where open/closed syllable adjustment (loi de position) applies, the presence of a circumflex accent is not taken into account in the mid vowel alternations /e/~/ɛ/ and /o/~/ɔ/.

[6] The merger of /ɑ/ and /a/ is widespread in Parisian and Belgian French, resulting for example in the realization of the word âme as /am/ instead of /ɑm/.

[7] Although normally the grave accent serves the purpose of differentiating homographs in French (là ~ la, où ~ ou, çà ~ ça, à ~ a, etc.

These recommendations, although published in the Journal officiel de la République française, were immediately and widely criticized, and were adopted only slowly.