Cis–trans isomerism

Cis–trans isomers are stereoisomers, that is, pairs of molecules which have the same formula but whose functional groups are in different orientations in three-dimensional space.

Cis and trans isomers occur both in organic molecules and in inorganic coordination complexes.

Cis and trans descriptors are not used for cases of conformational isomerism where the two geometric forms easily interconvert, such as most open-chain single-bonded structures; instead, the terms "syn" and "anti" are used.

In the same manner, symmetry is key in determining relative melting point as it allows for better packing in the solid state, even if it does not alter the polarity of the molecule.

In the case of geometric isomers that are a consequence of double bonds, and, in particular, when both substituents are the same, some general trends usually hold.

[8] In the Benson heat of formation group additivity dataset, cis isomers suffer a 1.10 kcal/mol stability penalty.

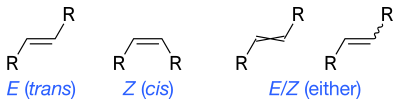

The IUPAC standard designations E and Z are unambiguous in all cases, and therefore are especially useful for tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes to avoid any confusion about which groups are being identified as cis or trans to each other.

Wavy single bonds are the standard way to represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers (as with tetrahedral stereocenters).

A crossed double-bond has been used sometimes; it is no longer considered an acceptable style for general use by IUPAC but may still be required by computer software.

Coordination complexes with octahedral or square planar geometries can also exhibit cis-trans isomerism.

The cis isomer, whose full name is cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), was shown in 1969 by Barnett Rosenberg to have antitumor activity, and is now a chemotherapy drug known by the short name cisplatin.

In the cis isomer, the two Y ligands are adjacent to each other at 90°, as is true for the two chlorine atoms shown in green in cis-[Co(NH3)4Cl2]+, at left.