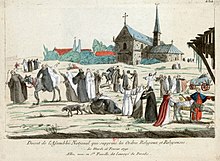

Civil Constitution of the Clergy

[2] Additionally, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy regulated the current dioceses so that they could become more uniform and aligned with the administrative districts that had recently been created.

No doubt, those who hoped to reach a solution amenable to the papacy were discouraged by the consistorial address of March 22 in which Pius VI spoke out against measures already passed by the Assembly; also, the election of the Protestant Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne to the presidency of the Assembly brought about "commotions" at Toulouse and Nîmes, suggesting that at least some Catholics would accept nothing less than a return to the ancien régime practice under which only Catholics could hold office.

François de Bonal, Bishop of Clermont, and some members of the Right requested that the project should be submitted to a national council or to the Pope, but did not carry the day.

"[2] In effect, this banned the practice by which younger sons of noble families would be appointed to a bishopric or other high church position and live off its revenues without ever moving to the region in question and taking up the duties of the office.

During the debate on that matter, on 25 November, Cardinal de Lomenie wrote a letter claiming that the clergy could be excused from taking the Oath if they lacked mental assent; that stance was to be rejected by the Pope on 23 February 1791.

On 26 December 1790, Louis XVI finally granted his public assent to the Civil Constitution, allowing the process of administering the oaths to proceed in January and February 1791.

Pope Pius VI's 23 February rejection of Cardinal de Lomenie's position of withholding "mental assent" guaranteed that this would become a schism.

Conversely, refusal to make the oath signaled a rejection of the Constitution and, implicitly, the legitimacy of the French government (at the time, still including the King).

[1][page needed] On 16 January 1791 approximately half of those the law required to take the oath did so, with the remainder awaiting the decision of Pope Pius VI on what exactly swearing it signified and the appropriate response.

[3][page needed] Additionally, the Pope expressed disapproval of the Constitution of the Clergy in general and chastised King Louis XVI for assenting to it.

[3][page needed] The law’s domestic opponents protested that the Revolution was destroying their "true" faith and this was also seen in the two groups of individuals that were formed because of the oath.

[1][page needed] The oath controversy marked a turning point in the revolutionary process since it was the first piece of the Assembly’s agenda that provoked widespread opposition.

[14] While there was a higher rate of rejection in urban areas[citation needed], most of these refractory priests (like most of the population) lived in the countryside, and the Civil Constitution generated considerable resentment among religious peasants.

On 5 February 1791, non-juring priests were banned from preaching in public[3][page needed] in the hope that this would silence the opposition to the Constitution from religious quarters.

[13] However, non-juring clergy were permitted to celebrate the Mass and attract crowds because the Assembly feared that stripping them of all of their powers would create chaos and arouse sympathy for its clerical opponents.

The Assembly was forced to moderate because the "Constitutional Clergy" (those who had taken the oath) were rejected by many of their parishioners; lifting some of the restrictions on non-jurors was seen as necessary to arrest the growing schism in the French church.

Louis XVI vetoed this decree (as he also did with another text concerning the creation of an army of 20,000 men on the orders of the Assembly, precipitating the monarchy's fall), which was toughened and re-issued a year later.

Although the Constitutional Church remained tolerated, it did not escape the most violent phase of the Revolution unscathed; the National Convention considered Catholicism in any form suspicious.

He voted in the Convention with the Girondins, exerted himself against the King’s condemnation, prohibited clerical marriage in his jurisdiction and expressed deep sorrow for the errors and scandals both of his political and ecclesiastical career.

After the Revolutionary government retook the city, Joseph Fouché arrested Lamourette, personally stripped him of his vestments and rode him through town on a donkey with a mitre on its head and a Bible and crucifix tied to its tail, so the mob could spit at and kick him.

Thereafter, he humbly made the sign of the cross, renounced his oath, and declared that he had been the author of all the speeches upon ecclesiastical affairs which Mirabeau had delivered in his own name in the Constituent Assembly.

[21] The agreement also gave the French government the right to nominate bishops, reorganize parishes and bishoprics, and allowed for seminaries to be established or re-established.

[21] In an effort to please Pope Pius VII, Napoleon agreed to subsidize the salaries of clerics in exchange for the legitimization of the state seizure of church property.