Historiography of the French Revolution

This trend was challenged by revisionist historians in the 1960s who argued that class conflict was not a major determinant of the course of the Revolution and that political expediency and historical contingency often played a greater role than social factors.

These included Edmund Burke's conservative critique Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) and Thomas Paine's response Rights of Man (1791).

By the mid-19th century, more scholarly histories appeared, written by specialists and based on original documents and a more critical assessment of contemporary accounts.

The first is represented by reactionary writers who rejected the revolutionary ideals of popular sovereignty, civil equality, and the promotion of rationality, progress and personal happiness over religious faith.

The Revolution was a conspiracy of philosophers and literary men who undermined faith in religion, monarchy, and the established social order, inciting "the swinish multitude" to create disorder.

[7] In France, conspiracy theories were rife in the highly charged political atmosphere, with the Abbé Barruel, in perhaps the most influential work Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797–1798), arguing that Freemasons and other dissidents had been responsible for an attempt to destroy the monarchy and the Catholic Church.

[8] Adolph Thiers' Histoire de la Révolution française (published 1823-27) was the first major work of the liberal tradition of French historiography.

The book played a notable role in undermining the legitimacy of the Bourbon regime of Charles X, and bringing about the July Revolution of 1830.

Writing in the liberal tradition, Mignet saw the Revolution of 1789 as the result of a growing, more prosperous and better educated bourgeoisie which challenged the inequalities of the old regime.

The liberal aristocrats and middle classes that led the revolution sought to establish a constitution, representative institutions, and equal political and civil rights.

According to Kidron, Mignet's history is notable for its lack of moral judgment and it presentation of the Terror as the acts of a war government against its enemies.

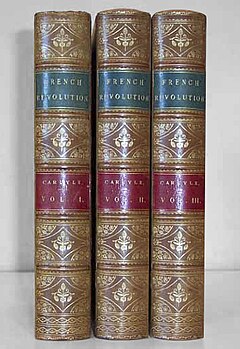

Carlyle rejected Thiers' deterministic view of history which emphasised inexorable historical forces over individual moral responsibility.

Carlyle was more interested in the lived experience of individuals and declared that Mirabeau, Danton and Napoleon were the three great men of the Revolution.

[20] Rudé and Doyle place Michelet in the radical, democratic republican tradition,[19] while Kidron describes the work as romantic, liberal and nationalist.

[23] Tocqueville was a political liberal who argued that the Revolution was led by thinkers without practical experience who had put too much emphasis on equality over liberty.

[25] Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893) in his Origines de la France contemporaine (1875–94) used archival sources extensively and his interpretation emphasised the role of popular action.

His interpretation was conservative and marked by hostility towards the revolution and revolutionary crowds which he claimed were mainly composed of criminal elements.

[32][33] From the 1960s, the dominance of social and economic interpretations of the Revolution emphasising class conflict was challenged by revisionist historians such as Alfred Cobban and François Furet.

[36] As a parliamentarian, he was instrumental in establishing the state-funded "Jaurès Commission", responsible for publishing historical documents and monographs on the Revolution.

[28] Alphonse Aulard (1849–1928) was the first professional historian of the Revolution; he promoted graduate studies, scholarly editions, and learned journals.

According to Aulard,From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life....

[32] Georges Lefebvre (1874–1959) was a Marxist historian who wrote detailed studies of the French peasantry (Les paysans du Nord (1924)), The Great Fear of 1789 (1932, first English translation 1973) and revolutionary crowds, as well as a general history of the Revolution La Révolution française (published 1951–1957).

He mentored a generation of historians who generally wrote cultural, social and economic interpretations defending the achievements of the Revolution.

[32] Albert Soboul (1914–1982) was a leading Marxist historian who was Chair of French Revolution History at the Sorbonne from 1968 to 1982 and president of the Société des Études Robespierristes.

In their influential La Revolution française (1965), Furet and Denis Richet argued for the primacy of political decisions, contrasting the reformist period of 1789-91 with the following interventions of the urban masses which led to radicalisation and an ungovernable situation.

[34] Furet later argued that a clearer distinction needed to be made between analyses of political events, and of social and economic changes which usually take place over a much longer period than the Jacobin-Marxist school allowed.

[51][52] Some other influential historians of this period are: From the 1980s, Western scholars largely abandoned Marxist interpretations of the revolution in terms of bourgeoisie-proletarian class struggle as anachronistic.