Tartan

[57] An old-time practice, to the 18th century, was to add an accent on plaids or sometimes kilts in the form of a selvedge in herringbone weave at the edge, 1–3 inches (2.5–7.6 cm) wide, but still fitting into the colour pattern of the sett;[57][58] a few modern weavers will still produce some tartan in this style.

The tartan fabric (along with other types of simple and patterned cloth) was recovered, in excavations beginning in 1978, with other grave goods of the Tarim or Ürümqi mummies[134] – a group of often Caucasoid (light-haired, round-eyed)[135][136] bodies naturally preserved by the arid desert rather than intentionally mummified.

There are several other continental European paintings of tartan-like garments from around this era (even back to the 13th century), but most of them show very simple two-colour basic check patterns, or (like the Martini and Memmi Annunciation example) broad squares made by thin lines of one colour on a background of another.

[171] The earliest surviving image of a Highlander in what was probably meant to represent tartan is a 1567–80 watercolour by Lucas de Heere, showing a man in a belted, pleated yellow tunic with a thin-lined checked pattern, a light-red cloak, and tight blue shorts (of a type also seen in period Irish art), with claymore and dirk.

[193] Its dense weave requiring specialised skills and equipment, tartan was not generally one individual's work but something of an early cottage industry in the Highlands – an often communal activity called calanas, including some associated folk singing traditions – with several related occupational specialties (wool comber, dyer, waulker, warp-winder, weaver) among people in a village, part-time or full-time,[195] especially women.

[235] A 1653 map, Scotia Antiqua by Joan Blaeu, features a cartouche that depicts men in trews and belted plaid; the tartan is crudely represented as just thin lines on a plain background,[236] and various existing copies are hand-coloured differently.

Daniel Defoe, in Memoirs of a Cavalier (c. 1720) wrote, using materials that probably dated to the English Civil War, of Highlanders invading Northern England back in 1639 that they had worn "doublet, breeches and stockings, of a stuff they called plaid, striped across red and yellow, with short cloaks of the same".

[263][ak] M. Martin (1703) wrote that the "vulgar" Hebridean women still wore the arisaid wrap/dress,[264] describing it as "a white Plad, having a few small Stripes of black, blue, and red; it reach'd from the Neck to the Heels, and was tied before on the Breast with a Buckle of Silver, or Brass", some very ornate.

[246] Edmund Burt, an Englishman who spent years in and around Inverness, wrote in 1727–1737 (published 1754) that the women there also wore such plaids, made of fine worsted wool or even of silk, that they were sometimes used to cover the head, and that they were worn long, to the ankle, on one side.

[295][296] Another surviving Culloden sample, predominantly red with broad bands of blue, green, and black, and some thin over-check lines, consists of a largely intact entire plaid that belonged on one John Moir; it was donated to the National Museum of Scotland in 2019.

[370] After the Jacobite uprisings, raising a regiment in service to the king was, for many Scottish lairds, a way of rehabilitating the family name, assuring new-found loyalty to the Hanoverian crown, and currying royal favour (even regaining forfeited estates).

[358] After the Highland regiments proved themselves fearless and effective in various military campaigns, the glory associated with them did much to keep alive, initially among the gentry and later the general public, an interest in tartan and kilts, which might have otherwise slipped into obscurity due to the Dress Act's prohibition.

[412] According to National Galleries of Scotland curator A. E. Haswell Miller (1956):[408] To sum up, the presumed heraldic or "family badge" significance of the tartan has no documentary support, and the establishment of the myth can be accounted for by a happy coincidence of the desire of the potential customers, the manufacturer and the salesman.

Aside from the outright forgery of the "Sobieski Stuarts" (see § 19th century broad adoption, below), another extreme case is Charles Rogers, who in his Social Life in Scotland (1884–86) fantastically claimed that the ancient Picts' figural designs – which were painted or tattooed on their bodies, and they went into battle nude [423]– must have been "denoting the families or septs to which they belonged" and thus "This practice originated the tartan of Celtic clans.

[358] In 1829, responding negatively to the idea of Lowland and Borders "clans" wearing their own tartans, Sir Walter Scott – who was instrumental in helping start the clan-tartans fervour in the first place – wrote "where had slept this universal custom that nowhere, unless in this MS. [the draft Vestiarium Scoticum, published ultimately in 1842] is it even heard of? ...

[560] Scott himself was backpedalling away from what he had helped create, and was suspicious of the recent claims about "ancient" clan tartans: "it has been the bane of Scottish literature and disgrace of her antiquities, that we have manifested an eager propensity to believe without inquiry and propagate the errors which we adopt too hastily ourselves.

[584] By 1849, John Sobieski Stuart was in discussion with a publisher to produce a new, cheaper edition of Vestiarium, in a series of small volumes "so that it might be rendered as available as possible to manufacturers and the trades in general concerned in Tartan ... and it was for the[ir] advantage and use ... that I consented to the publication."

[587] In the same year, Authenticated Tartans of the Clans and Families of Scotland by William & Andrew Smith was based on trade sources such as Wilsons, competing mill Romanes & Paterson of Edinburgh, and army clothier George Hunter's pre-1822 collection of setts (and some consultation with historian W. F.

[659] Because Scott had become "the acknowledged preserver of Scotland's past" through his historical novels, the legend he helped create of tartan and Highland dress as a Scotland-wide tradition rooted in antiquity was widely and quickly accepted, despite its ignoring and erasing of cultural diversity within the country[652] (of Gaels, Norse–Gaels, Scoto-Normans, and Lowlanders of largely Anglo-Saxon extraction).

[697] The visit involved her large royal party being met with several theatrical tartan-kilted welcomes by Highland nobility and their retinues, with much sycophantic newspaper fanfare (while the common people were experiencing considerable misery); the Queen wrote: "It seemed as if a great chieftain in olden feudal times was receiving his sovereign".

[720] Despite their considerable devotion to charity (up to 20% of their Privy Purse income),[721] Victoria and Albert, along with their friends in the northern gentry, have been accused of using their "Balmorality" – a term coined by George Scott-Moncrieff (1932) to refer to upper-class appropriation of Highland cultural trappings, marked by "hypocrisy" and "false sentiment" – to trivialise and even fictionalise history.

"[746] Even the 1822 "King's Jaunt" had been stage-managed by two Scots with a keen interest in romanticising and promoting Gaelic and broader Scottish culture (historico-traditional accuracy notwithstanding),[652] and the Atholls' deep and tartan-arrayed involvement in Victoria's activities in the north can be viewed in the same light.

A tartanistical fantasy, as well as another exercise in "Highlander as noble savage", the art book necessitated canvassing Scottish aristocrats for outfits and suitable models ("specimens"), as the everyday people did not look the hyper-masculine part, were not able to afford such Highland-dress extravagances as were to be illustrated, and were more likely to be wearing trousers than kilts.

Harry Lauder (properly Sir Henry – he was knighted for his war-effort fundraising during World War I) became world-famous in the 1910s and 1920s, on a dance hall and vaudeville entertainment platform of tartan Highland dress, a thick Scots accent, and folksy songs about an idealised, rural Scotland, like his hit "Roamin' in the Gloamin'".

"[793] In 2006, the British Ministry of Defence sparked controversy when it allowed foreign woollen mills to bid for the government contracts to provide the tartans used by the Scottish troops (newly amalgamated as battalions into the Royal Regiment of Scotland), and lowered the formerly very high standards for the cloth.

[822][823] Large-scale global manufacturers of tartan-patterned cloth in a variety of cotton, polyester, viscose, nylon, etc., materials and blends include Başkan Tekstil in Istanbul and Bursa, Turkey; and Jeen Wei Enterprises in Taichung, Taiwan; while a leading maker of tartan ribbon is Satab in Saint-Just-Malmont, France.

A British court on 2 July 2008 issued an interim interdict (preliminary injunction) against Gold Brothers' sale of Isle of Skye goods, after a police search found hundreds of metres of the pattern in Chinese-made cloth in the company's warehouse.

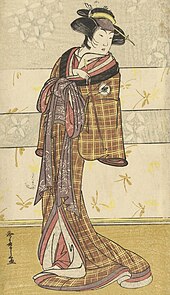

In Japan, tartan patterns called kōshi 格子 (also koushi or goushi, literally 'lattice') or kōshijima 格子縞 date back to at least the 18th century,[408] possibly the 17th[1018] in the Edo period (1603–1867), and were popular for kabuki theatrical costuming, which inspired general public use by both sexes, for the kosode (precursor of the kimono), the obi, and other garments.

Robert Jamieson, writing in 1818 as editor of Edmund Burt's 1727–37 Letters of a Gentleman in the North of Scotland, said that in his era, married women of the north-western provinces of Russia wore tartan plaids "of massy silk, richly varied, with broad cross-bars of gold and silver tissue".

[1027][1028] Around the end of the 19th century, the Russian equivalent of Regency and Victorian British tartanware objects, such as decorative Fedoskino boxes with tartan accents in a style called Shotlandka Шотландка (literally 'Scotlandish'), were produced by companies like the Lukutin Manufactory on the outskirts of Moscow.